eBook - ePub

God the Holy Trinity (Beeson Divinity Studies)

Reflections on Christian Faith and Practice

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

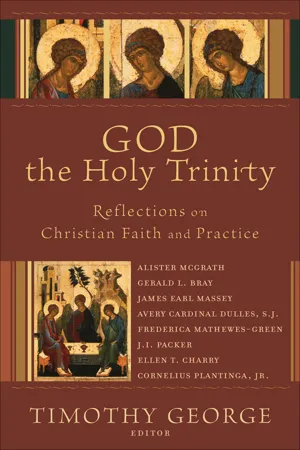

God the Holy Trinity (Beeson Divinity Studies)

Reflections on Christian Faith and Practice

About this book

God the Holy Trinity brings together leading scholars from diverse theological perspectives to reflect on various theological and practical aspects of the core Christian doctrine of the Trinity. Throughout, the contributors highlight the trinitarian shape of spiritual formation. The esteemed lineup of contributors includes Alister E. McGrath; Gerald L. Bray; James Earl Massey; Avery Cardinal Dulles, S.J.; Frederica Mathewes-Green; J. I. Packer; Timothy George; Ellen T. Charry; and Cornelius Plantinga Jr. This book will appeal to students, church leaders, and interested laity. It is the second book in the Beeson Divinity Studies series.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access God the Holy Trinity (Beeson Divinity Studies) by George, Timothy, Timothy George in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Theology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Doctrine of the Trinity

An Evangelical Reflection

ALISTER E. MCGRATH

One of my fonder childhood memories concerns a church service in Northern Ireland, in the late 1950s. I was growing up, totally disinterested in the Christian faith, but still feeling the cultural pressure to self-identify religiously and attend church. The Book of Common Prayer was still the only authorized form of worship, and we religiously—I think I can safely use that word!—followed its seventeenth-century English prose. On one occasion, for reasons that I cannot entirely recall, we said the Athanasian Creed. As we recited its rather ponderous statements, we came to affirming our belief in “the Father incomprehensible, the Son incomprehensible, and the Holy Ghost incomprehensible.” I can still recall the loud voice of a slightly deaf local farmer, standing by my side, booming out: “The whole damn thing’s incomprehensible.” The congregation had paused for breath at that particular point and had no difficulty in hearing this piece of theological commentary.

At that stage, I have to admit that I had no particular interest in religion, regarding attending church as one of life’s less exciting inevitabilities. But some such thought has haunted the Western church throughout its history, particularly since the rise of the “Age of Reason” in the eighteenth century. Is the doctrine of the Trinity simply an intellectual incoherence? Perhaps it is the classic example of an outdated and outmoded demand that we, like Lewis Carroll’s Alice, should believe “as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”[1] There is no difficulty in identifying many who feel this way. While navigating that international superhighway of human knowledge and wisdom called the Internet, I came across the site www.religionisbullshit.com, making some quite strident comments on the matter, in which the words “illogical” and “irrational” featured prominently.

Common Anxieties about the Trinity

Here I want to explore this deep sense of unease that many have concerning the coherence of the doctrine of the Trinity, and how it casts light on both the theological enterprise and the issues we face in addressing our cultural situation. I begin by teasing out some aspects of the “irrationality” of the doctrine of the Trinity. Above all others, this doctrine provides us with a prism through which we may understand the traditions and tasks of Christian theology, as well as highlighting some concerns about recent directions that it has taken. To begin, I focus on issues of rationality.

The first point is obvious and rather well-worn but nevertheless merits constant repetition. There are limits to what we can understand. The first and most inconvenient of all theological responsibilities is to recognize our limitations. We can explore these at three different levels: human finitude, human creatureliness, and human sinfulness. In each of these respects, we are highlighting an aspect of our existence as finite, fallen creatures. This condition is laden with implications for our competence as thinkers and actors, and above all for our thinking and acting in relation to God. We can see this in relation to both revelation and salvation, two leading themes of Christian theology that affirm our incapacity to describe and encounter God under conditions of our own choosing, and in terms that we have determined in advance. Rationalism is epistemic Pelagianism. The first point to make, therefore, is that we must expect that our frail, sinful, and limited human capacity to reason will be severely tested when trying to accommodate itself to the divine reality. Indeed, many leading Christian theologians—and I mention Origen, Erasmus of Rotterdam, and John Calvin as obvious examples—point out that God accommodates himself to our weakness in revelation.

A second point would be that, in the relatively recent past, it was customary to excoriate the doctrine of the Trinity as irrational nonsense. If Christianity was not capable of stating its thinking about God in ways that resonated with common sense, thinking people need not take it seriously. Yet as the Enlightenment vision of human reason’s scope relentlessly loses credibility, that erosion diminishes the force of this complaint to a near vanishing point. Even the notion of “common sense” is now regarded as socially constructed. As Alasdair MacIntyre explained in his Three Rival Versions of Moral Enquiry, philosophy in general and ethics in particular cannot proceed by means of reasoning from neutral, self-evident facts accepted by all rational persons. He concedes that many intellectuals of the late Victorian period believed exactly that, confusing the customs of their time with universal truths. However, we simply cannot sustain this view. Nearly everything philosophers have proposed as a “universal category,” immune from the irritations of historical specificity, has found itself beached and shipwrecked.[2]

MacIntyre’s contention that the Enlightenment proposed a theoretical criterion of justification that no one could meet in practice is of fundamental importance to the theological task. What the Enlightenment theoretically proposed no one could put into practice. People gradually realized that this massive tension between theory and practice represented more than an irritating anomaly that a later generation would sort out. It was the fatal flaw of the Enlightenment project as a whole. The Enlightenment insisted that whether something could be understood and rationally justified determined its credibility. But then the Enlightenment found itself in the rather tiresome position of having to acknowledge that it was just as “particularist” as the positions it believed it could critique from the Olympian heights, far above the specifics of history and culture.

My third point takes us off in a slightly different direction and builds once more upon growing impatience with the overstatements of the Enlightenment. One of the more troubling aspects of the Enlightenment agenda is its desire to dominate. To understand something is essential before it can be mastered. Understanding is the first step in a process of bringing something or someone to submission.

On Failing to Master God

In one sense the doctrine of the Trinity is our admission—as beings created and finite, fallen and flawed—that we simply cannot fully grasp all that God is. Was not Augustine right when he pointed to the limitations placed on our capacities, and their devastating impact on the theological enterprise? Si comprehendis, non est Deus.[3] One human response to this has been to argue that, since we cannot possibly grasp the mystery of God, we might as well content ourselves by creating something rather more manageable. The human desire to understand is interlocked with the darker desire to dominate. Those of us who have wrestled with the ideological program of modernity are uncomfortably aware of what Bruno Latour describes as “the double task of domination and emancipation.”[4] If we are to master something, such as the natural world, we must first understand it. What Augustine termed the “eros of the mind”—meaning the sheer ecstatic delight of knowledge for its own sake—thus easily decays and degenerates into something rather more sinister. Knowledge is acquired, not to delight in the Other, but to dominate it, forcing it to serve our needs and our ends.

The doctrine of the Trinity represents a chastened admission that we are unable to master God. As Thomas Aquinas pointed out in the thirteenth century, the theologian who tries to master God is rather in the position of Jacob wrestling with the angel at Peniel (Gen. 32:24); the theologian emerges from the event bruised and defeated, yet the wiser and better for the engagement. For Augustine, to “comprehend” was to intellectually subjugate something, to proclaim the victory of the human intellect over all that it surveys. Yet Augustine was quite clear: we simply cannot “comprehend” God.

Writers sympathetic to the goals of the Enlightenment protest that such theological strategies are simply retreats into irrationalism. Yet it is important to pause and adjudicate this claim. The Enlightenment used the term “rational” in a triumphalist sense, often with a hidden meaning. Rational means what reason can account for, thus validating its own claim to mastery and autonomy. By designating what it could not master as “irrational,” the Enlightenment sought to deflect attention from those aspects of reality—including the vision of God—that were clearly too much for human reason to cope with. Those areas of reality that reason could not conquer were not declared to lie beyond reason, but to be contrary to reason.

The Enlightenment now lies behind us, leaving us stranded as we seek to secure adequate criteria for knowledge, as opposed to mere opinion. With the long, lingering death of the cult of reason has come the rebirth of interest in the concept of mystery, understood in its proper sense as a matter of intellectual immensity, which our frail and finite human minds simply cannot grasp in its totality. In short, we are confronted with a mystery.

Reclaiming the Notion of “Mystery”

This brings me to my final point concerning the Trinity and rationality: the recent revalidation of the concept of mystery. On a Christian reading of the world, the coherence of reality is not something that is optimistically and improperly imposed upon a formless or inchoate actuality, but something that can be discerned, within the limits of our capacities as created beings. The Christian vision of things affirms the ultimate coherence of reality, so that we can hold the occasional opacity of things to reflect a mystery rather than an incoherence. Perceptions of incoherence are thus to be understood as noetic, rather than ontic, as resting on our limited capacity to perceive and to represent, rather than on the way things actually are.

Faced with a mystery, in the proper sense of the term, human beings tend to take one of two approaches: First, they may declare it to be an incoherence, which therefore need not detain us, save as offering a textbook example of primitive or superstitious beliefs, which the modernist enterprise worked so hard to eliminate. Second, they may reduce it to something more manageable, arguing that while the totality of the mystery may lie beyond us, we may be able to grasp at least some of its aspects. While both of these strategies are understandable, they are theologically problematic.

The doctrine of the Trinity gathers together the richness of the complex Christian understanding of God; it yields a vision of God to which the only appropriate response is adoration and devotion. The doctrine knits together into a coherent whole the Christian doctrines of creation, redemption, and sanctification. By doing so, it sets before us a vision of a God who created the world, whose glory can be seen reflected in the wonders of the natural order; a God who redeemed the world, whose love can be seen in the tender face of Christ; and a God who is present now in the lives of believers.

In this sense, we can reckon the doctrine to “preserve the mystery” of God, in the sense of ensuring that the Christian understanding of God is not impoverished through reductionism or rationalism. The Brazilian liberation theologian Leonardo Boff also makes this point:

Seeing mystery in this perspective enables us to understand how it provokes reverence, the only possible attitude to what is supreme and final in our lives. Instead of strangling reason, it invites expansion of the mind and heart. It is not a mystery that leaves us dumb and terrified, but one that leaves us happy, singing and giving thanks. It is not a wall placed in front of us, but a doorway through which we go to the infinity of God. Mystery is like a cliff: we may not be able to scale it, but we can stand at the foot of it, touch it, praise its beauty. So it is with the mystery of the Trinity.[5]

So how do we wrestle with a mystery? I will offer two pointers, one drawn from the Reformation, the other from the twentieth century. One of the central themes of Martin Luther’s “theology of the cross” is that we are to regard the cross as a mystery.[6] By this, Luther means that human reason is incapable of fully grasping the doctrine, which it therefore seeks to restate on its own terms. We can never hope to give a full account of the cross; although we can certainly delineate its many revelational, soteriological, and spiritual aspects, we cannot hope fully to plumb the depths of its meaning. Luther does not see this as a problem; it is simply the way things are, involving a chastened and responsible admission on the part of human theologians that they are not divine. The human mind’s creaturely and fallen status limits it. What we can know about God we can indeed know reliably; yet we cannot fully know God.

Here Luther is stating the principle of “reserve,” a leading theme in both the Cappadocian fathers and in more recent writers, such as John Henry Newman. God gives human intellect and reason, which are not contrary to revelation; yet they cannot apprehend all the mysteries of faith and must learn to accept the limitations under which they are obliged to operate.

In the twentieth century, Hans Urs von Balthasar develops a related line of thought. Von Balthasar insists upon the “totality” of the divine revelation, holding that it necessarily exceeds human comprehension. To develop this idea, he draws on the notion of Gestalt, a term used by Christian von Ehrenfels (1859–1932), the Austrian founder of Gestalt theory, to designate complex wholes that simply cannot be reduced to their constituent components. We are to see the whole as more than, and other than, the sum of its individual parts.[7] Von Balthasar applies such insights to the notion of revelation, which he insists is ultimately irreducible.[8]

Conceding the human need and impulse to “dissect” such a Gestalt, von Balthasar argues that this represents an attempt to “master” revelation,[9] and hence to subjugate it. Beholding the Gestalt as a totality forces us to concede the inadequacy of our fragmented approaches to mystery. We cannot hope to see behind the mystery; we must look for meaning within it, accepting the limitations on comprehension and representation that this entails.

We can understand the point at issue by considering the famous distinction Gabriel Marcel (1889–1973) developed between “problems” and “mysteries.”[10] Marcel sees reality as existing on two levels, the world of the problematical and the world of the ontological mystery. For Marcel, the world of the problematical is the domain of science, rational inquiry, and technical control. Here we define the real by what the mind can conceptualize as a problem and hence solve and represent in a mathematical formula. Reality is merely the sum total of its parts. In the world of the problematical, one therefore views human beings essentially as objects, statistics, or cases, and defines them in terms of their vital functions (biological) and their social functions; one thus considers the individual as merely a biological machine performing various social func...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 The Doctrine of the Trinity: An Evangelical Reflection

- 2 Out of the Box: The Christian Experience of God in Trinity

- 3 Faith and Christian Life in the African-American Spirituals

- 4 The Trinity and Christian Unity

- 5 The Old Testament Trinity

- 6 A Puritan Perspective: Trinitarian Godliness according to John Owen

- 7 The Trinity and the Challenge of Islam

- 8 The Soteriological Importance of the Divine Perfections

- 9 Deep Wisdom

- Notes

- Contributors

- Index