1

The Wrong Place at the Wrong Time

RUNWAY INCURSIONS

It all started with a terrorist bomb. It exploded in the passenger terminal at the Las Palmas Airport in Gran Canaria, a popular tourist destination in the Canary Islands located off the northwest coast of Africa. The airport was closed, and many aircraft were diverted to the Los Rodeos Airport on the nearby island of Tenerife. It didn’t take long before this small airport was overwhelmed with aircraft: The apron was crammed with passenger jets, and air traffic controllers (ATC) even had to direct aircraft to park on the only taxiway. Fortunately, within a few hours Las Palmas reopened, and crew members began their preparations for departure.

The air traffic controllers had their hands full, and to make things more difficult, low clouds and fog rolled in reducing their ability to see the runway and making it harder for the pilots to see each other’s aircraft.

Flight 4805, a KLM Royal Dutch Airlines Boeing 747, filled mostly with tourists happy to be back on their way to Las Palmas, was cleared to back-taxi (backtrack in Canadian terminology) on the runway. A few minutes later Pan American Clipper Flight 1736, another Boeing 747 also filled with tourists glad to be moving again, was cleared to back-taxi on the same runway behind the KLM B-747. The air traffic controller intended for KLM 4805 to taxi to the end of the runway and turn around, while the Pan Am Clipper was to exit the runway and continue to its threshold via the remaining parallel taxiway. Unfortunately, the Clipper crew was having difficulty locating its exit in the dense fog. As a result, the Clipper was still on the runway when KLM 4805 had turned around and aligned for departure at the threshold of Runway 30. Due to a variety of communication problems, the KLM captain thought he had been cleared for takeoff and was certain the Pan Am aircraft was clear of the runway. Unfortunately, he was wrong on both counts. He commenced the takeoff and the aircraft had reached takeoff speed when he first saw the Pan Am jet ahead on the runway. He desperately tried to get his aircraft airborne to clear the other B-747, while the Pan Am crew frantically tried to steer their aircraft off to the side of the runway to avoid a collision, but there simply wasn’t enough room—the aircraft collided, killing everyone on the KLM 747 and most of the people aboard the Pan Am 747.

All told, 583 people perished that March afternoon in 1977, making it the deadliest accident in aviation history. Amazingly, it occurred while the aircraft were still on the ground, making it also the worst runway incursion accident of all time. Defined several ways since then, the United States and Canada now use the runway incursion definition adopted by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) in 2005. Simply stated, a runway incursion is the incorrect presence of an aircraft, vehicle, or person on a runway.

At the time of this writing, the Flight Safety Foundation’s Aviation Safety Network has identified the occurrence of more than 65 major runway incursion accidents worldwide that were responsible for the loss of more than 1,250 lives. Seven of these occurred in the United States in one decade alone (the 1990s). Runway incursions don’t necessarily result in tragedy; there are literally hundreds of these events each year in the United States and Canada, but fortunately most don’t result in accidents. A surface event can be classified as a runway incursion even if there is no conflict with a departing or arriving aircraft; the runway environment is intended to be protected, and any time that protection breaks down it results in a potential threat to safety.

The most effective way to reduce the threat of a runway incursion collision is to reduce the number of runway incursions themselves. Unfortunately, since the mid-1990s, as airport traffic has increased and airport ground operations have become increasingly more complex, the incidence of runway incursions has increased almost exponentially. Transport Canada (TC) recorded a 145 percent increase in runway incursions in the four years between 1996 and 1999, and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) observed a similar trend, albeit not as steep.,

In response, both organizations implemented significant improvements to the aviation system to help reduce the number of runway incursions (we will look at some of these improvements later in this chapter). However, in spite of their efforts, the number of runway incursions continued to gradually increase in both countries. There were more than 4,200 runway incursions at towered airports in the United States (controlled airports in Canada) between 2004 and 2008 with an increase of 39 percent over that five-year period. (The FAA tracks runway incursions only at towered airports, and therefore the statistics do not include the many surface events involving aircraft operating at nontowered airports.) Both the FAA and TC continue to work with airport operators, ground crews, air traffic controllers and pilots to prevent these potentially serious occurrences; however, runway incursions remain a major hazard as evidenced by their presence on the National Transportation Safety Board’s (NTSB’s) Most Wanted List of safety improvements since it was first created in 1990 until 2013.

What’s So Hard About Navigating on the Apron?

Your task is deceptively simple: Navigate from the apron to the active runway so that the “real” flight can begin. After your flight is over and the wheels are back on the ground, it’s simply a matter of finding your way to the parking spot. It’s this apparent simplicity that leads to a certain degree of complacency about the task. Add to this the fact that the crew might have two or three checklists to complete while navigating across wide open tarmac, often containing confusing signage, and it’s easy to see how an error might be made while taxiing.

Environmental Conditions

Most runway incursions occur during the day in visual meteorological conditions (VMC), but statistics indicate that the majority of runway incursion accidents occur in conditions of reduced visibility, or at night, or both. In fact, all six fatal runway incursion accidents involving major U.S. air carriers or regional airlines in the 1990s occurred during the hours of darkness (or at dusk) or in fog. It’s simply more difficult to navigate on the airport at night or in poor visibility.,

Crossing Active Runways

A review of runway incursion accidents and incidents provides dramatic examples of what can go wrong. One of the most common runway incursion scenarios at busy airports involves aircraft that must cross one or more active runways in order to reach their destinations. The following narrative from the captain of a de Havilland DHC-8-30, as reported in the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS), is a typical example:

After initiating the takeoff, our aircraft accelerated rapidly due to having a light load for that flight. During the takeoff, a C-182 crossed the runway downfield on what appeared to be Taxiway R. The C-182 was crossing the runway at a rapid rate, and by the time the first officer saw it downfield, it was crossing the center of the runway. We were at or near V1 at this time, and seeing the aircraft clearing the runway he elected to continue. He rotated and we were off the ground prior to reaching Runway 5/23. I contacted tower after arriving at our destination and was told that the C-182 was instructed to “taxi and hold short” twice. On both occasions, the pilot read back the hold short instructions and still failed to hold short of our runway (ASRS Report No: 823234).

It was fortunate the Dash 8 was light enough and had the climb capability to clear the Cessna. The Cessna 182 Skylane pilot was twice cleared to “taxi and hold short” of the active runway, and as required by the FAA Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM), he correctly read back his runway hold instructions both times. While taxiing, it’s easy to become distracted by tasks such as programming the global positioning system (GPS), completing a checklist, or talking with passengers. You can lose awareness of your position relative to the active runway—especially at an unfamiliar airport—and become aware of the runway only as you cross it. Although hold-short lines are typically marked with yellow lines on the pavement, and red and white holding position signs are located alongside the hold-short point on the taxiway—and in some cases in-pavement lighting is also provided—pilots continue to cross onto active runways, largely due to distraction.

Lining Up and Waiting on the Active Runway

The probability of a ground collision increases when you’re cleared to taxi into position on the runway. ATC will often issue such a clearance to provide better spacing between aircraft. Pilots who have been instructed to “line up and wait” have lined up with the runway, but all too often have not waited—instead they have initiated their takeoff roll without receiving a clearance. This is often simply a result of habit. Pilots generally enter the runway, line up with the centerline, complete the runway items on the before-takeoff checklist, advance the throttles and depart. This sequence of events becomes so automatic that they sometimes start the takeoff roll even though they haven’t been cleared for takeoff.

An almost fatal illustration of this occurred at Quebec/Jean Lesage International Airport when a Cessna 172 was cleared to “taxi to position” on one runway about 16 seconds after an Air Canada Airbus A320 had been cleared for takeoff on another intersecting runway. The Cessna pilot conducted a takeoff departure without a clearance. According to the Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB), the controller instructed the pilots of both aircraft several times to abort, but the tower transmitter had been temporarily disabled so the transmissions weren’t heard by either of the pilots. The A320 was nearing its rotation speed as it approached the intersection of the two runways, and the Cessna was already in the air climbing through about 200 feet. The captain of the A320 instructed the first officer (FO), who was the pilot flying (PF), to delay rotation until after they had passed the intersection of the two runways. A collision was avoided by only about 200 feet! (TSB Report No: A04Q0089)

Wrong-Runway Departures

Of course, the probability of a collision on the ground increases if pilots taxi to, and depart from, the wrong runway. An early 1990s NASA study of rejected takeoff (RTO) incidents found a surprising number of wrong-runway takeoffs—and even taxiway takeoffs—conducted by otherwise qualified commercial airline pilots! This type of error was more recently committed by the flight crew of Comair Flight 5191 in the early morning hours of August 27, 2006. It didn’t result only in the risk of a collision with another aircraft, vehicle or person; it led to something worse.

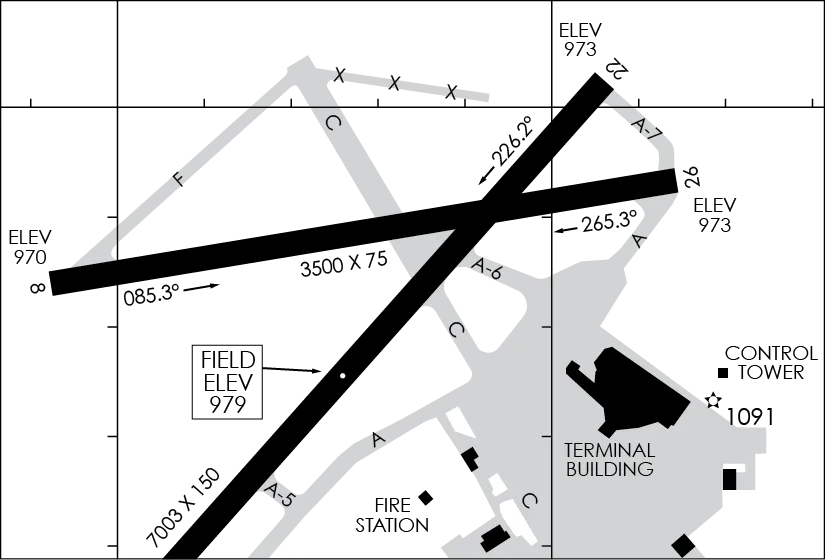

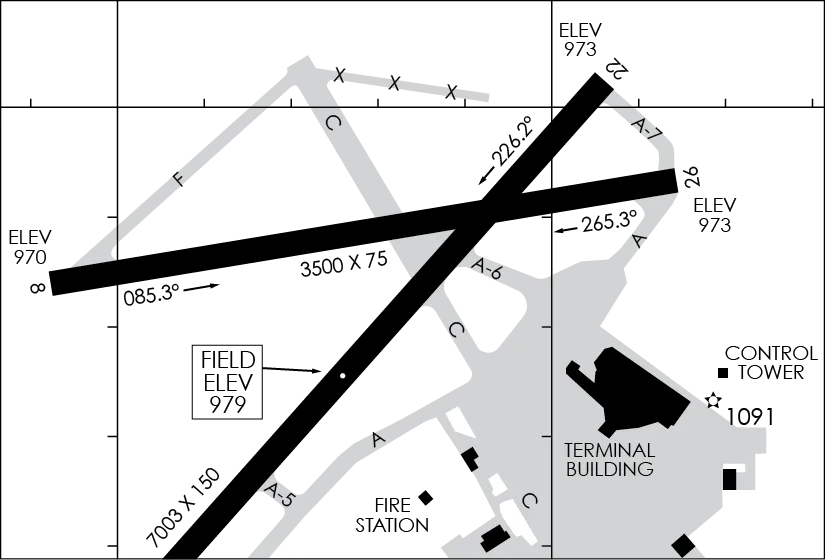

The crew arrived at dispatch at 5:15 a.m. local time to prepare for a 6:00 a.m. departure from Blue Grass Airport in Lexington, Kentucky. The preflight preparations, including engine start and taxi, were relatively normal, although there were a few minor slip-ups that suggest the crew members may not have been as focused on the task as they optimally could have been. For instance, they initially boarded the wrong airplane and had to be redirected to the aircraft intended for the flight. The radio work and checklists included some minor slips and momentary confusion. According to the NTSB report, the crew also engaged in some non-operational conversations when they should have been focusing on the task of taxiing to the runway. They were cleared to taxi their Bombardier CL-600 Challenger to Runway 22 (the 7,000-foot runway) and cleared to cross Runway 26 during their taxi. The diagram shown in Figure 1-1 illustrates that in order to reach the threshold of Runway 22 from the terminal building, the crew had to taxi past the threshold of Runway 26.

Figure 1-1. Diagram of Blue Grass Airport, Lexington, Kentucky.

Visibility that morning was about seven miles, but it was dark at the time of takeoff—sunrise wasn’t until 7:00 a.m., and the moon was well below the horizon. The taxiway they needed to take (Alpha 7) was a slight left turn, as illustrated in Figure 1-1, but when they encountered the threshold for Runway 26, they turned a full 90 degrees to the left and lined up on the wrong runway. The air traffic controller didn’t notice the error and cleared them for takeoff. The result was that Flight 5191 departed on a runway with insufficient takeoff distance (only 3,500 feet long) and hit an earthen berm a few hundred feet past the end of the runway. Everyone on the airplane was killed with the exception of the FO who suffered serious injuries (Report No: NTSB/AAR-07/05).

Wrong-runway takeoffs occur more frequently at airports where two o...