![]()

(Photo by Amy Hoover)

![]()

![]()

This chapter explores en route procedures, including route selection, maneuvering in canyons, visual illusions, terrain flying, and emergency turns. Plan a route that considers your airplane’s performance, wind and weather, and your comfort level in remote mountainous areas (Chapters 2 and 3). Use lower-elevation passes to cross high-altitude terrain, and follow roads, major river drainages, and canyons. Use cruise climbs and descents to maximize performance and safety.

Altimeter Settings

Because remote mountain and backcountry airstrips often have no weather reporting, you will use the field elevation to set your altimeter before departure. Your altimeter can be off by several hundred feet after crossing a drainage divide into another area that is in a different pressure system (see Chapter 2). Study the charts beforehand and identify different drainage systems and potential locations where pressure might change dramatically. Altimeter errors could cause you to fly a pattern that is too high or too low if you rely solely on the altimeter. Thus, it is important to learn to use visual cues in addition to instruments to determine your height above the ground.

Check and reset your altimeter before every departure. Verify altimeter settings with other pilots in the area but be cautious, since they may not have set their altimeter before departure.

Visual Illusions

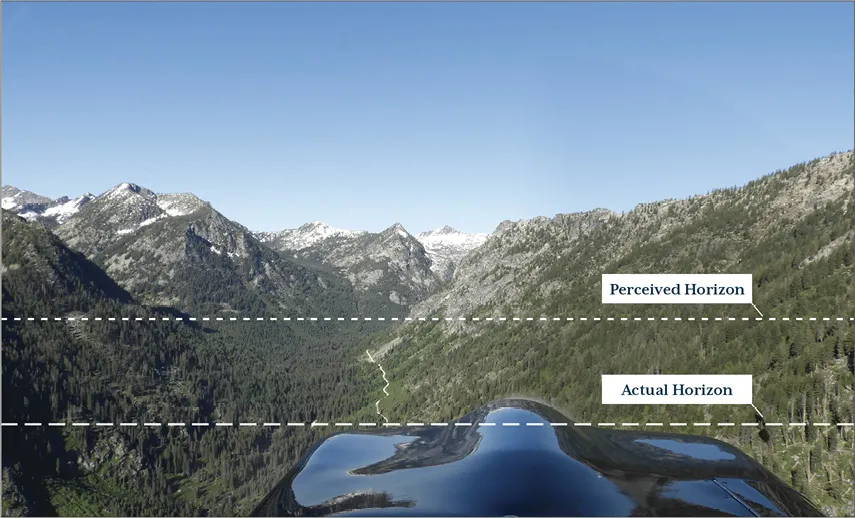

As noted by the Transportation Safety Board of Canada, “The illusions encountered in the mountains are dangerous for those who do not have the experience or the training to recognize and compensate for them” (Transportation Safety Board of Canada [TSB], 2011). One of the most common visual illusions is the inability to recognize the true horizon. In mountainous areas and especially in canyons, terrain blocks the actual horizon, and pilots typically perceive it as being higher than it actually is (Figure 4-1). The typical response to the illusion in level flight is to initiate a climb in an attempt to fly what appears to be level. Continuing this slow, even imperceptible, climb can result in loss of airspeed to the point of becoming hazardous if the pilot fails to recognize the situation.

Figure 4-1. Position of the actual horizon and the perceived horizon. In level flight, a typical response is to climb, which can cause a dangerous loss of airspeed. (Photo by Amy Hoover)

Baldwin captured the essence of the dangers to pilots who fail to recognize this visual illusion:

We are born into a level world. We crawl on level floors, sit at level tables, play sports on level playing fields and otherwise spend our lives leveling cabinets, refrigerators, and picture frames. When we start out in our flying career we learn to level off, level our wings and go straight and level. We are so level oriented that we psychologically crave level even in our uneven world. It is so pervasive that we will assign level to something even if it isn’t and fail to acknowledge the obvious signs that scream out the contrary. (Baldwin, 2010)

The obvious signs are an increase in pitch attitude and decreasing airspeed. This is a good reason to cross-reference your airspeed indicator and use all your senses to help understand the situation. For example, your engine sound will change in a climb. Continuously having to advance the throttle to “stay level” is a warning that you are either in a downdraft or are climbing due to a visual illusion. Regardless of which it is, the response should be the same. Look straight ahead and envision level, cross-reference your airplane instruments, and do not climb. Visual reference to upsloping terrain perceived as level will cause you to ascend and your airplane might not be able to out-climb the gradient.

Another factor that contributes to spatial disorientation is uneven terrain. Using the slope of the mountainside or canyon wall as a visual horizon, especially during turns, can cause you to lose sense of the actual horizon, especially with no sky visible. For example, in the traffic pattern at a canyon airstrip, terrain can block all reference to the actual horizon, and you may not be able to see anything but sheer rock and canyon walls everywhere you look. Developing a visual sense for this type of maneuvering takes practice, and novices can quickly become disoriented. Some methods to overcome visual illusions while turning are discussed later in this chapter.

Before flying in mountain and canyon terrain, there are ways you can develop depth perception. For example, glider pilots develop depth perception to accurately estimate altitude above the ground in case they need to make an off-field landing during cross-country flights. That training transfers well to mountain and canyon flight. Practice by covering your altimeter (first ensuring it is correct), estimating your height above the ground over a known elevation, and then checking it with the altimeter until you can be accurate within 200 feet or less.

Crossing Ridges

The safest way to cross ridges is to have plenty of altitude. Most mountain flying recommendations suggest a clearance of at least 1,000–2,000 feet of altitude above ridge level, depending on the conditions (Imeson, 2005; Anderson, 2003; Levi & O’Meara, 1992). Try to cross at the lowest point or through a mountain pass or saddle. Choose a location that is more like a knife-edge rather than a broad, flat plateau that takes more time to cross.

Performance limitations may require you to fly at lower altitudes, so you need to know how to cross ridges at or near ridge-top level. Ensure you have adequate terrain clearance before attempting to cross. If more terrain becomes visible beyond the ridge as you approach, then you should clear the ridge (unless there is a downdraft). If the ground beyond the ridge disappears as you approach, you will not clear it, so turn away and gain more altitude before attempting to cross. An overlying cloud base may restrict your altitude, so make sure the mountain tops are not obscured by clouds or you could enter the cloud before clearing the ridge. Use caution in this situation, as it is easy to head down the wrong canyon under low ceilings (Figure 4-2). Avoid cutting through a ravine or drainage when ridge tops are obscured, as there may not be room to turn around to the other side.

Figure 4-2. Low clouds and ceilings obscure mountain and ridge tops, making it hard to distinguish canyons. A low ceiling may obscure the ridge tops and you might not be able to clear the terrain before entering the cloud. (Photo by Amy Hoover)

Constantly monitor the conditions behind you if the weather is deteriorating and ensure you will always be able to continue ahead or turn back. It may help to periodically make a 360-degree turn to assess the weather behind and to the sides of your flight path.

Expect downdrafts on the downwind (or leeward) side of a ridge. Allow sufficient altitude to provide a wide margin of safety when crossing. On the windward side, updrafts might help you gain altitude to clear the ridge, but do not count on that. However, be aware that severe updrafts could carry you upward into an overlying cloud layer. Try to determine the wind direction at all times and seek out lift and updrafts to help remain at safe altitudes.

Regardless of which side you approach a ridge, saddle, or pass, always cross at an angle that allows a turn back or escape toward lower terrain, preferably a 45-degree angle or less. Avoid entering directly into small cul-de-sacs where it is not possible to turn around. Continuously update your mental “picture” of how you will turn back, and update your escape plan often.

A smaller approach angle can give you a better view of terrain on the other side of the ridge and requires a shallower bank if you need to turn away from the ridge. Your planned escape route must be downhill or downstream and free of obstacles. Once you have cleared the ridge or pass, fly away from it at a 90-degree angle, if terrain permits. That will get you out of turbulence and downdrafts as quickly as possible. As stated by the Civil Aviation Authority of New Zealand:

Remember Murphy’s Law of mountain flying: when you need to turn back, it will be through sink, turbulence and a tailwind—so make sure you have the space and height available to do it safely. Don’t rely on aircraft performance to get you out of trouble—good anticipation and good decisions are required. (CAA of New Zealand, 2012)

Slow to maneuvering speed (VA) or below in wind, and anticipate wind shear as you cross a ridge, especially...