![]()

1

Part One

Airplane Performance and Stability for Pilots

![]()

1

Airplane Performance and Stability for Pilots

A Review of Mathematics for Pilots

A pilot doesn’t have to know calculus to fly an airplane well, and there have been a lot of outstanding pilots who could add, subtract, multiply, and divide—and that’s about it. But since you are going to be an “advanced pilot,” this book goes a little more deeply into the whys and hows of airplane performance, including a little math review.

Trigonometry

Trigonometry can turn into a complex subject if you let it, but the trigonometry discussed here is the simple kind you’ve been using all along in your flying and maybe never thinking of it as such.

Take a crosswind takeoff or landing: you’ve been using Tennessee windage in calculating how much correction will be needed for a wind of a certain strength at a certain angle from the runway centerline. You correct for the crosswind component and know that the headwind component will help (and a tailwind component will hurt).

You have been successfully using a practical approach to solving trigonometric functions. (If an instructor had mentioned this factor earlier, some of us might have considered quitting flying.)

What it boils down to is this—whenever you fly you’re unconsciously (or maybe consciously) dealing with problems that involve working with the two sides and hypotenuse of a right triangle. Flight factors involved include (1) takeoffs and landings in a crosswind, (2) max angle climbs, (3) making good that ground track on a VFR or IFR cross-country, (4) working a max range curve (if you are an engineer, too), and (5) calculating max distance glides. The following chapters will cover all these areas of performance in more detail.

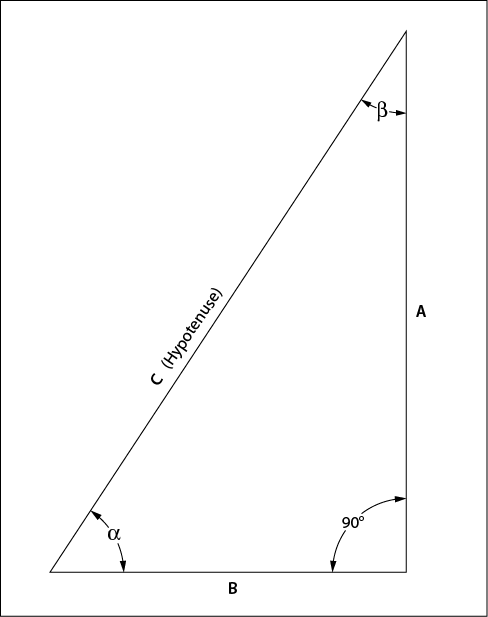

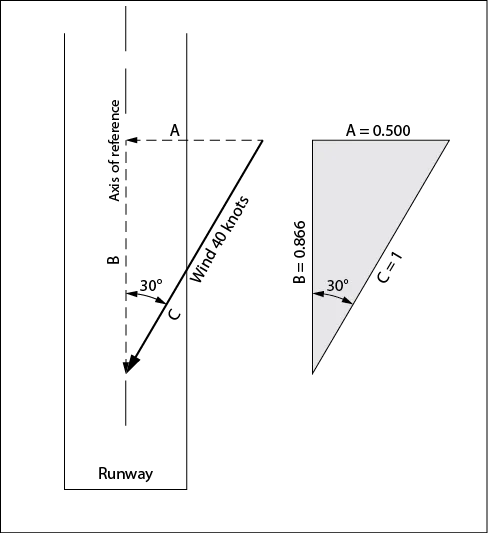

Looking at a takeoff in a crosswind, you’re dealing with the sines and cosines of a right triangle, a triangle with a 90° angle in it (Figure 1-1).

Figure 1-1. Right triangle components.

Sine

The sine (normally written as “sin,” which perks it up a little) for an angle (α here) is the ratio of the nonadjacent side A to the hypotenuse (side C) (Figure 1-1). The Greek letters α (alpha) and β (beta) are used for the angles here because, well, it gives the book more class, and the Greek letters are used in aerodynamics equations. More Greek letters will be along shortly. The sides of a triangle are normally denoted by our alphabet (A, B, C).

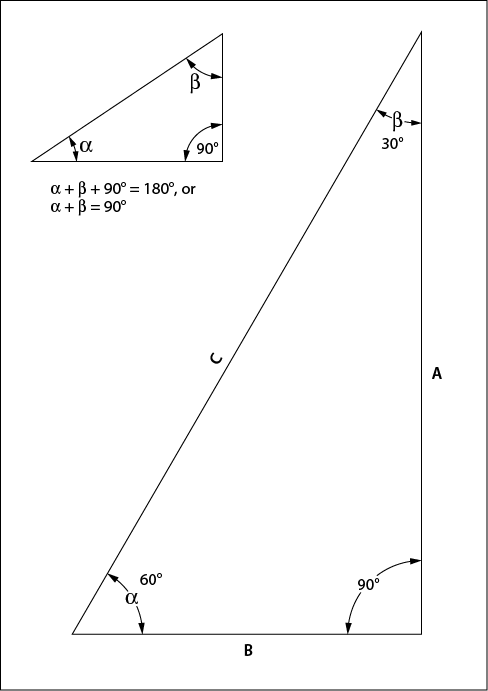

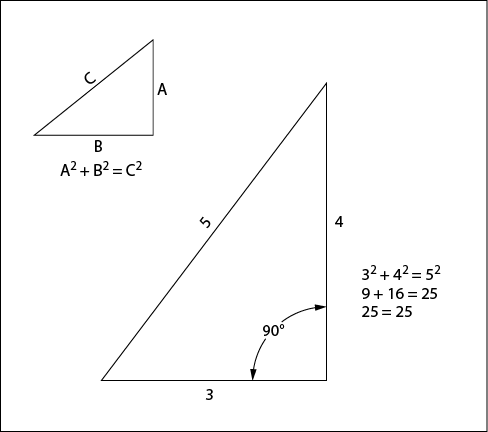

Look at a 30°-60°-90° triangle (Figure 1-2). The internal angles always add up to 180°; thus the other two angles of the right triangle (which has a 90° angle) always add up to 90° (10° and 80°, 45° and 45°, etc.). Another interesting point about right triangles is that the sum of the squares of the two sides is equal to the square of the hypotenuse, or A2 + B2 = C2 (Figure 1-3). (This is what the Scarecrow recited after the Wizard of Oz gave him a diploma—and a brain.)

Figure 1-2. A right triangle with 30° and 60° acute (less than 90°) angles.

Figure 1-3. Classic example of the relationship of the hypotenuse of a right triangle. (Another is a triangle with 7 and 24 sides and a 25 hypotenuse: 72 + 242 = 49 + 576 = 625; 252 = 625).

Cosine

For a 30° angle (β in Figure 1-2), the relationship of sides A and C (the hypotenuse), side A is always 0.866 of the length of side C (the cosine of 30° is 0.866; A/C = 0.866). Engineers add a zero before the decimal point for a value less than 1 so that it is clear that there isn’t a missing number.

Looking at the angle α in Figure 1-2, note that the relationship of length of the adjacent side B at the 60° angle to the hypotenuse (side C) is the cosine of that angle, always 0.50 (B/C = 0.50).

Looking from the same angle of 60° (α), it is a fact that the sine (the nonadjacent side A divided by the hypotenuse, or A/C), is 0.866; that is, the length or value of side A is 0.866 the length of the hypotenuse. The sine of the 60° angle is the same as the cosine of a 30° angle—and why not? That’s the same side (A). For side B, 0.500 is the cosine of the 60° angle and the sine of the 30° angle. (Got that?)

(Figure 1-2)—cosine | α = B/C = 0.500 |

sine | β = B/C = 0.500 |

Take a practical situation: You are taking off in a jet fighter from a runway with a 40-K wind at a 30° angle to the centerline. What are the crosswind and headwind components? You’re working with a right triangle with 30° and 60° acute angles (Figure 1-4). Solving for the crosswind component for the wind at a 30° angle you find that the ratio of A to C is 0.50 to 1, or one-half. The component of wind working across the runway is 0.50 of the total wind speed of 40 K, or a 20-K crosswind component, which means the same side force as if the wind were at 20 K at a 90° angle to the runway.

Figure 1-4. Finding the headwind and crosswind components.

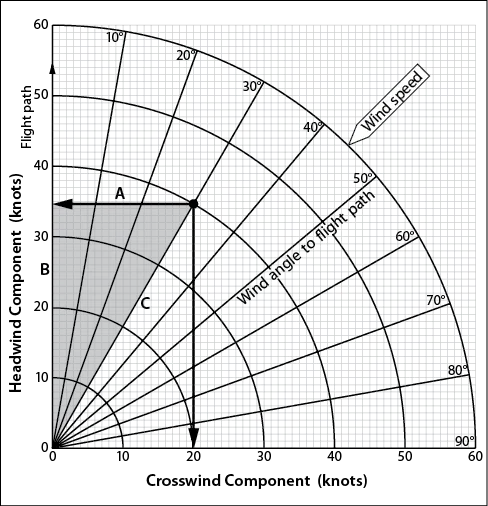

To make takeoff calculations in the Pilot’s Operating Handbook (POH), you need to know the headwind component (B/C), or the cosine of the 30° angle, which is always 0.866. So, 0.866 × 40 K is 34.64 K. (Just call it 35 K.) If, however, the wind was 60° to the runway at 40 K, the situation would be reversed and the crosswind component would be 0.866 × 40 = 34.64 (35) K (and the headwind component would be 0.50 × 40 = 20 K), as can be seen by checking the graph (Figure 1-5). What we’ve started here is a wind component chart like that found in a POH; here the engineers work out the sines and cosines for various angles the wind may make with the runway and all you have to do is read the values off the graph. Note that the triangle in Figure 1-4 and the shaded area of Figure 1-5 are the same. The wind speed in the graph is always the hypotenuse (side C) of the triangle.

Figure 1-5. The wind component chart is a prepared set of right triangles, with sines and cosines precalculated and drawn. Horace Endsdorfer, private pilot, assumes that Figure 1-5 can only be used for crosswinds from the right, since that’s the way it’s drawn, but Horace has other problems as well (see Chapter 7—Endurance).

Tangents

The tangent is the relationship between the far side (the nonadjacent side) and the near side (the side adjacent to the angle in question). Look back at Figure 1-2. The relationship A/B is the tangent of the angle α (60° shown there), and looking ahead at Figure 1-8 you can see that the tangent of 60° is 1.732. In a 60° angle, side A is 1.732 times as long as side B. The tangent is useful in such factors as finding the angle of climb, where the relationship of feet upward versus feet forward is essential.

To digress a little, Figure 1-6 shows the p...