eBook - ePub

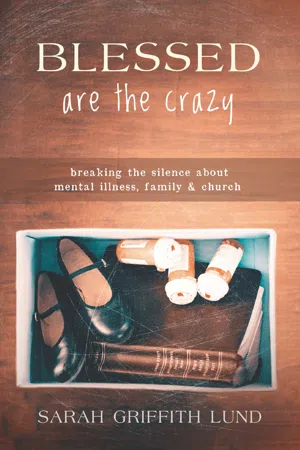

Blessed Are the Crazy

Breaking the Silence about Mental Illness, Family and Church

- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Blessed Are the Crazy

Breaking the Silence about Mental Illness, Family and Church

About this book

When do you learn that "normal" doesn't include lots of yelling, lots of sleep, lots of beating? In Blessed Are the Crazy: Breaking the Silence about Mental Illness, Family, and Church, Sarah Griffith Lund looks back at her father's battle with bipolar disorder, and the helpless sense of déjà vu as her brother and cousin endure mental illness, as well. With a small group study guide and "Ten Steps for Developing a Mental Health Ministry in Your Congregation, " Blessed Are the Crazy is more than memoir-it's a resource for churches and other faith-based groups to provide healing and comfort. Part of The Young Clergy Women Project.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Blessed Are the Crazy by Sarah Griffith Lund in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Religion

chapter 1

Learning to Testify

I am five years old. Sometimes my dad is scary. He likes everything to be lots: lots of eating, lots of adventures, lots of sleep, lots of work, lots of yelling, lots of beating, lots of laughing. But he doesn’t like lots of me. I don’t see him lots. Mommy says he sleeps at the animal hospital now so I snuggle up with her in the California king bed and we cuddle because I am the baby. I am number five. We are Susan, Scott, Steve, Stuart, and Sarah.

It is Sunday morning now. We are in church. My shoes are black. I swing them, tapping the wood with my toes. The singing stops and Mommy holds my hand and says, “It’s time to go up.” My family stands in line like getting ready for recess, but we don’t play in church. Dad says church is for praying, not playing. The minister gives the big people snacks, but this is not snack time because I don’t get any. The wafers and wine are not for kids. They are parts of God’s body. When it is my turn I put my knees on the pillow and cross my arms over my heart. The minister’s big hand covers my head and he leans over me whispering, “May God bless you in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.” My head feels warm. I don’t look up. I look down at my dress and count the hearts on it but some are half hearts at the edges. Do the broken hearts count?

My brothers are next to me at the altar and the older two boys are breaking the rules by being rude, making farting sounds and laughing. I didn’t fart. We hurry back to sit down. More singing but Dad is not happy. He is crying. Mommy holds my hand. And when the song is over we pray and go home.

Sometimes after church we get fancy pie but not today. Dad is driving the car fast past the pie place. My brothers cry out for pie. Dad says we were bad in church, so no pie for bad children. But I wasn’t bad. My brothers cry out, “We want pie!” And the car stops. Dad gets out of the car and pulls off his belt. He opens the car door and grabs my oldest two brothers. They scream with their pants down and their underwear touches their shoes. He whips them and the other cars on the road drive by fast. They get back into the car. This time Mommy is crying. I wish the hearts on my dress were stickers; then I would use them for band-aids.

It is night time. But Dad needs help at the animal hospital and we all want to go. On the way there we get snacks at the drive-thru. We get lots of paper bags with twenty hamburgers and French fries. Dad is hungry tonight and needs energy for work. There are two dogs scheduled for surgeries so my brothers and sister help my dad in the operation room. Being the baby means that I am too little to do the surgeries. I go down the hall to the room with the cages where all the cats and dogs sleep. I crawl into an empty bottom cage and pretend I am a cat. Today I don’t have to clean the stinky cages and throw away the pee pee newspaper.

Only the dogs are getting surgeries now, not me or my brothers or sister. If we get sick or hurt we go to the animal hospital and get dog shots because we are the same size as dogs. Just the other day when I cut my head open jumping on the bed, Dad said to wrap it in a wet towel to stop the bleeding. Mommy wanted to call the doctor but Dad said no. Now we know that whenever there is blood to get into the shower. My head stopped bleeding, but you can still feel a dent. I close the wire door and stay inside the cage until it’s time to go home.

Home Is Where God Is?

Home is where God is, but God wasn’t always living with us at 1908 Angola Avenue in California. If God is love, my ten-year-old mind reasoned, then how could God live in a house where there is such hate? I wondered that when my dad and my oldest brother, Scott, were having one of their fights. This time it got so bad that Dad chased him out of the house. I followed them, wanting to see for myself what happened next. Would this be the time that my dad killed my brother or would it be the other way around? This time Dad confiscated my brother’s prized skateboard and started to drive off in the truck, probably going to throw it in the city dump. Just then my brother ran up to the truck door and hurled his thin body through the open window, practically climbing into my dad’s lap to get his skateboard back. But when my brother leaned in, the truck suddenly reversed and my brother smacked to the ground, screaming, the truck tires screeching as my dad drove off down the street. While my brother lay there writhing in pain with a fractured leg, I saw the look of betrayal and abandonment on his bloody face. Dark streams of blood stained his dirty blond mohawk. God gave us the most horrible, twisted, and awful father who ever lived. Without a doubt he hated us all and he was going to kill us.

Soon after the hit-and-run, Mom dragged us all to family counseling to figure out what to do. She wanted to know if she could save her marriage and keep the family safe from our father’s rages. The counselor stared at us through thick black-framed glasses and then asked us kids to vote. He said to raise our hands up high if we wanted to split the family up and leave our father behind in his own miserable mess. In the dimly lit room I was unsettled. This man who looked so serious—did he really not know what we should do? I shrank in the darkness of the unknown. I couldn’t move my hand, let alone think about moving my whole life.

What I did know was that my stomach hurt, bad. In it was a feeling that something was irreversibly wrong, hitched to a sense of an impending domestic nuclear disaster. After the counseling appointment we went home and packed black trash bags with underwear, shoes, shirts, and shorts. Into superhero and Strawberry Shortcake pillowcases we stuffed pieces of our childhood: handmade baby blankets, baby books, and home videos of births. The Christmas ornaments given to me by my godparents, several from each of my ten years, were considered unessential. We crammed all this into the blue and white Suburban, along with our bodies—five kids and a mom—plus the roll top desk and grandfather clock. Mom couldn’t bear to part with those.

That summer, in the middle of the night, with pregnant avocados hanging heavy on the tree branches, we left Angola, moving out in secret, without saying a word to any of our friends. We moved to Missouri to live with my mom’s parents. If God is good, then God was glad that we were finally gone from that house where hate scared love away.

Moving to Missouri put geographic distance between me and my father, but the fear of him remained smack dab in the middle of my heart. He figured out right away what we had done and he tracked us down, making harassing phone calls to my grandparents’ house where we stayed. He threatened their lives too, blaming them for stealing his children. My mother warned me to never go with my father anywhere if he showed up to take me, and to never let him into the house. In addition to my chronic stomach pain I started wetting the bed. With my dolls I made up imaginary worlds. We needed to go to the doctor, but didn’t. No money. But still…nothing was so bad now, was it? We were all still alive.

My father remained in California while we made Missouri our new home. In California we had lived in a ranch house, had a live-in nanny, gardeners, and a pony. In Missouri, Mom worked as a public school teacher, but Dad didn’t pay child support. Mom explained that he wasn’t being lazy; he couldn’t work because of his disability. Whatever that was—no one would tell us exactly. When we weren’t in school, all five of us kids worked: paper routes, washing dishes, waitressing, tutoring, and babysitting. But we were still poor. Food stamps, free lunch programs at school, and secondhand clothes were all new to me. I repeatedly had to tell the cashier in the lunchroom, in front of my friends, that I was “free lunch.” I decided to bring my lunch to school and nobody needed to know it was paid for with food stamps. I could at least try to pretend I wasn’t poor.

How He Loved Us

That same year Dad managed to trick my mom and “abduct” my middle brother Steve for part of the junior high school year. At first Dad had both Steve and Stuart with him for a short visit during the summer, but Dad then decided to send Stuart home and keep Steve. Mom remembers picking Stuart up at the airport, shocked to find him by himself. She says that Stuart was so traumatized by his older brother Steve’s abduction (in part wondering why Dad hadn’t wanted him as well) that he was temporarily mute, in addition to his chronic stutter, and couldn’t tell Mom why Steve wasn’t with him or why he was sent back home on the airplane by himself.

Steve was just starting junior high and he remembers living with Dad in a God-forsaken part of Los Angeles, eating strictly a fast-food diet of fried chicken, burgers, milkshakes, and French fries. The small hotel room was crammed with piles of magazines, stacks of boxes, and old fast-food wrappers carpeting the floor. It was fun for Steve for a while, a new adventure, but it sort of got old and none of his friends were at his new school. I talked to Steve on the phone a few times when his allergies were bad. He sounded really stuffed up; maybe he wasn’t getting to the doctor. After a few months, my dad grew tired of my brother and sent him back to Missouri on an airplane with tickets purchased by my grandparents.

In my father’s world, he was a man of global political importance. He was distressed at being targeted and followed by undercover spies because he harbored secret information about a plot to kill the Queen of England. He knew he would be famous some day for his inventions, like underground tunnels connecting continents. He became totally brainwashed by Lyndon LaRouche, a political figure whose movement attracted followers with its claims to have secret, inside information about United States history and government. They boasted about ownership of privileged information about communist plots, assassination attempts, and scandalous connections to British aristocracy, as well as the hidden influences of Thomas Jefferson on modern politics. Instead of trying to repair our family, he joined LaRouche’s new family.

He was furious that we left him. He accused Mom of being a lesbian. He’d call to enlighten us about LaRouche. At first I sincerely tried to listen and understand what it was all about, but it got too weird. AIDS, he told us, was invented as a Soviet war machine. Harvard University is a center for fascism. The Episcopal Church is the assassination arm of British intelligence. Really?

I knew Dad was smart. He married my mom. I knew he had important ideas. He owned one of the first emergency animal hospitals in the city. But what I really didn’t know until later was that he was also sick. He covered up his mental illness so well, hiding it behind his intelligence, work ethic, charisma, and love for life. It was hard to tell sometimes whether he was manic or just excited about a new project. But as he got older, and we kids grew older, his mental illness remained untreated, and his symptoms grew more pronounced. It wasn’t until we moved to Missouri that I realized there was something wrong with the way Dad’s brain worked. He had a zig-zag way of telling us things. There was always another version of the truth, a secret story that only he knew.

My father mailed us boxes of “educational literature” from the LaRouche organization. We leafed through the pages, laughing in disbelief and concealed grief. In a way, the boxes were like care packages. I guess this propaganda was his love language, his way of communicating how much he cared about us. Where he had once insisted that we go to church, he had now adopted LaRouche as his religion, and now the salvation of his family was at stake. It was his job to save us. We didn’t throw out the boxes; we just stacked them in our basement family room right next to the Nintendo game station. My father’s slanted handwriting in black ink on the brown cardboard lid linked me to him. Inside those boxes there was some trace of my father’s love.

When he called the house I usually got stuck on the phone with him the longest because my brothers and sister refused to talk with him or only listened briefly and then handed the phone over to me. With one ear I would listen to him ranting manically nonstop about LaRouche while the other ear was trying to follow The Cosby Show on TV. The part of me that listened to him felt flattered to be the chosen one, and strangely loved by his attention, even if it was garbled nonsense. Somehow I was important to my father. Maybe there was a part of him that wasn’t crazy and could still love me? Maybe it was all a big mistake, a misunderstanding? He could get better if he wanted to, and, if he loved us enough, he would.

No One Asked

I even prayed about it, asking God to help me understand why love had to be so confusing and painful. Sunday mornings I ran down the street to church and headed straight to the donut table in the fellowship hall. The ministers and kind strangers at our church helped me know that not everything in my life was ruined. At ten, I liked going to church and hearing about my Father God and his love. It made my stomach not hurt so bad, despite my filling it with donuts.

Church taught me a lot about a loving God, but not how to tell my own story about love, or the lack of it. My Sunday school teachers wanted me to learn about God’s love for the world and that this love sent Jesus to save us. But no one in Sunday school ever asked me what I needed saving from in my own life. Bible truths would magically set us free from sin. Yet there was no place for us to name, in our own words, the sin in our lives, the sinfulness of our families, or the sinfulness of our world.

None of my closest friends knew my father was crazy. I buried all my feelings of abandonment, neglect, rejection, anger, and fear deep down inside. I spent time with my friends and their dads, the ones who coached my soccer team or drove me and my friends around after school; dads who were at home to eat family dinners. I spent lots of time at my best friend Jill’s house. She seemed to have the perfect life: only one brother, a mom, and a dad.

It’s seventh grade math class and I’m sitting at my desk in the back of the classroom trying to figure out the surface area of a cylinder. Someone comes into the classroom and hands the math teacher a note. The teacher calls my name and my heart races as I walk up front in-between the narrow rows of desks, embarrassed that my shorts are sticking to the back of my thighs. The freaky boy in the front row is looking at my big butt. The teacher hands me the note. It is yellow office paper and it says, “Sarah Griffith. Come to office. Father is here for early pick up.”

My mother is dead.

Why else would my father come all they way to Missouri from California to get me? That would be the only reason he would come. Confused and terrified I quickly walk back to my desk to get my pink Guess book bag. Running down the hallway and up the stairs to the school office, I fear for my life. What is going on? Where is my mom? Then I see him and my stomach knots. He’s waiting for me, sitting on the white plastic office chair. “Come on,” he says standing up, “let’s go.” I look to the school administrator, wondering if she thinks it is safe to go with him, and she smiles, nodding. She doesn’t know anything about my father. I do not say a word, but follow him out to the parking lot where we get into his rusted-out old truck. “So, where do you want to go? I thought we could get a bite to eat,” he says. He is oblivious to how scary and infuriating this is for me.

“Does Mom know you are here?” I ask. “No,” he says. I haven’t seen him for three years. He thinks he can take me out of school, and then try to buy my love with food. “Take me home now. I have to do my paper route,” I blurt out. “Oh, come on. Aren’t you hungry?” He laughs. “Let me get you something,” he argues. “I want to go home,” I repeat as I roll down the truck window. The clouds briefly cover the sun and a bird cries out.

He starts the truck and we putter out of the school parking lot. Across the street the dogwood trees are in bloom, and their white petals are traced with pink. I direct him how to get home. Thoughts race through my mind: What does he want with me? What if he doesn’t take me home? Even with the window down, I’m suffocating, trapped inside the truck with him. It smells like stale French fries. He drives slowly past our church before turning down the street to my house. My stomach turns somersaults.

The truck engine dies in front of my house on Highland Drive. The grass is too long and looks white trash; the gray house paint is peeling. “Thanks for the ride home,” I mutter while reaching for the truck door. His giant hand grabs my arm. “Stay with me,” he pleads. I pull my arm away from him and pause for a moment. I close my eyes and feel safety in the sunshine streaming down on me from above. Nothing bad can happen to me in the daylight. Now that I’m home, I’m almost free. He can’t hurt me here. He wouldn’t dare.

A green van pulls up into the driveway, and a guy unloads five bundles of newspapers, and piles them by the steps, one on top of another, before driving away. “Well, I’ve got to go do my paper route.” I open the truck door, grab my book bag, and get out. Closing the door I take a hard look at him. I don’t know who he is, really, or what he is capable of doing to me. I turn away. Walking up to the house I see the school bus coming and it stops at the tall oak tree. And there, in his dilapidated truck, my dad drives away, following the yellow school bus down the road.

Someone’s Girlfriend, Someone Else’s Story

Even though I have three older brothers, unless we were fighting over what food remained in the house, we pretty much ignored each other. The only boys I paid any real attention to were the ones who liked me. In junior high I discovered that boys gave me some of the attention and affection I craved, even if it wasn’t real love. Chasing and being chased by boys was a marvelous distraction from dealing w...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Definitions

- Foreword by Donald Capps

- Preface

- 1 Learning to Testify

- 2 Entrusting My Father to God’s Beloved Community

- 3 Caring for My Brother—How Would Jesus Do It?

- 4 Seeking the Holy Spirit on Death Row

- 5 Feeling Pain in God’s Presence

- 6 Blessed Are the Crazy

- Epilogue

- Afterword by Carol Howard Merritt

- Appendix: Ten Steps for Developing a Mental Health Ministry in Your Congregation and Mental Health and Faith Resources

- Notes

- Acknowledgments