- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Boundaries are healthy and necessary parts of life and ministry. Staying in Bounds provides straight-talk guidance to ministers and other leaders of churches and faith-based organizations on the what, why, and how of relational boundaries. Provides guidance on identifying, implementing, and enforcing healthy boundaries, with a special focus on ministry settings. The author develops the concept of boundaries from psychological and theological perspectives, discusses the benefits of boundaries, and then explains the importance of healthy boundaries in the church.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Staying in Bounds by Eileen Schmitz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theologie & Religion & Christliche Kirche. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

BOUNDARY APPLICATIONS IN MINISTRY

CHAPTER 8

Straight Talk on Power

“Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

JOHN EMERICH EDWARD DALBERG ACTON

“They are dogs with mighty appetites; they never have enough. They are shepherds who lack understanding; they all turn to their own way, each seeks his own gain.”

ISAIAH 56:11

Meaning, purpose, and significance are woven into the fabric of our self-concept and are needed for psychological and spiritual well-being. People naturally search for meaning, purpose, and significance through relationship. Our relational nature allows us to experience a sense of wholeness and fulfillment as our inner experience is enriched by external relationships and by participation in a collective purpose greater than ourselves. It allows us to exist in community and to connect intimately with God and others.

Parishioners come into our churches looking for answers and guidance. People are attracted to the message of grace and hope that we preach. Identification with a congregation of believers provides parishioners with an environment that allows them to develop their self-concept, formulate meaning for their lives, creatively express their purpose, and receive affirmation of their significance. Pastors have the privilege and responsibility of facilitating their parishioners’ search for purpose and meaning; the most effective tools for this endeavor are presence and relationship. As we carry out this responsibility, we want to conduct ourselves with mercy, justice, and humility. We strive to develop characteristics of integrity, authenticity, and empathy in our personal and professional lives. Ideally, we pursue our vocation of ministry not primarily for personal gain, but in response to a holy calling. Our focus is on serving with honorable and uncompromising ethical and moral standards.

So why is it that clergy are by all accounts the most likely to be reported for misconduct and moral failure by the news media? Even taking into account the media’s insatiable appetite for sensationalism, it is sobering that—in a profession that advocates in principle for morality, holy living, and service to others—the frequency of moral failure, misconduct, and abuse is noteworthy, if not astounding. And for every report that becomes public fodder, there are many, many more instances of misconduct that are not scandalous enough for the evening news. These instances remain private, hushed, or quietly “managed.”

Worse yet, the only breaches of ethical behavior that typically come to public awareness are those of sexual misconduct, child abuse, and financial misappropriation. The general public is largely unaware of the less egregious boundary violations (which may ultimately lead to more appalling breaches) that result in personal harm, hurt, and loss to parishioners and pastors alike, and compromise parishioners’ spiritual and psychological growth.

Clergy are human too, with human needs, human souls, and human brokenness.1 Pastors experience the same challenges as their parishioners to balance personal needs with the needs of others, to find significance in their own lives and to maintain healthy boundaries. But the challenge that pastors face is intensified: pastors must prevent their position from becoming an opportunity to violate boundaries in order to fulfill their personal needs.

Power and Responsibility

Motivating the spiritual growth of others is a weighty responsibility because with responsibility comes accountability (Heb. 13:17). It is also a heady responsibility, for it intimates a special emissary relationship with the Almighty2 and fosters the perception of the spiritual leader as a mediator and facilitator who is worthy of reverence and deference (cf. 1 Tim. 5). Fundamental to the position of pastor is power and with power comes an increased opportunity and susceptibility for misuse of the position. As with anything that is intended for good, the position of spiritual leadership can also be used in the wrong ways and for the wrong motives.

Power presupposes a relative difference in the ability of two people to influence one another. In chapter 2, we saw that a person who has greater sphere of influence—denoted by the larger circle—will have a proportionately greater impact on another person with a relatively smaller sphere of influence (i.e., less power). Also to be considered are the influence of both real power and perceived power. The extent of real power will vary between congregations and denominations, and depends on polity, congregational history, and the minister’s level of accountability to a governing board.

Figure 1. The Disproportionate Influence of the Minister on Parishioners

Perceived power is the level of deference or acquiescence to the pastor by the parishioners. Centuries of church history have led to a widespread notion that a “good” Christian is characterized by submission to church leaders. As with any guideline taken to the extreme, indiscriminate and absolute submission is not healthy and can lead to trouble. Although it is the responsibility of the pastor to not misuse the power intrinsic to the position of spiritual leader, indiscriminate submission is possibly the biggest contribution by parishioners to creating opportunities for the misuse of power.

Ann (A Parishioner Tells Her Story) exhibited indiscriminate submission to the authority of her pastor, Brad, presumably because she had not developed adequate self-concept and autonomy. Any time she felt slightly awkward with his demands, she attributed it to her defectiveness and deficiencies, rather than to his disregard for her boundaries, and so conceded on the basis of his position of power. Congregations that encourage or demand absolute and unquestioning submission to the pastor or other designated spiritual leaders will have to mop up the messes left behind by the inevitable misuse of power to violate boundaries. Therefore, power without accountability tends to corrupt, and “absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

Inherent in ministry are a number of forces that contribute to the power differential between pastor and parishioners, whether or not the pastor welcomes the increased power. These forces are tightly linked. Some of these forces are

- embodiment of hope

- implicit trust

- idealization

- intimacy

- ministry of prayer

- spiritual authority

- preaching

- administrative function

The Hope That Is in Us

Christian believers have something of value—hope. In a world filled with grief, existential angst, tragedy, and pain, the Christian message is one of hope and peace. If our hope is for real, it will show. People will notice. If our lives are permeated with peace, people who live in confusion will want to know the secret. “Always be prepared to give an answer to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that you have” (1 Pet. 3:15b). The first priority of ministry is to be a light or beacon that beckons with its inviting glow to those who are suffering in darkness and hopeless confusion. We want our hope to overflow so that it is unmistakable and contagious (Rom. 15:13). People will take note and recognize the power of God’s transforming love: “Neither do people light a lamp and put it under a bowl. Instead they put it on its stand, and it gives light to everyone in the house. In the same way, let your light shine before men, that they may see your good deeds and praise your Father in heaven” (Mt. 5:15–16).

The embodiment of hope is a characteristic, not an action. So, how does incarnating hope create a position of power? When others connect with us in search of hope, they are asking for help. We are in a position of influence and this creates a power differential. Our power can be used to invite others to embrace the same hope. In this case, we acknowledge that while we can explain the hope that is in us, it is not our business to coerce acceptance. We recognize that if we attempt to coerce acceptance, we will be taking on the responsibility of the Holy Spirit (Jn. 16:8) and challenging the boundary between God and us.

Our power also can be used more insidiously to encourage others’ dependence on us, to gain admiration, to build a following of “wannabes.” Sometimes people are attracted to a personality trait and attempt to assimilate that trait by imitation or association rather than by integration and personal ownership. They place their hope and salvation in their pastor, not God. In their minds the pastor becomes their redeemer. We can use our power of attraction to encourage a misplaced faith, in order to fill a personal need for feeling desirable, important, or significant. In Maryann’s story (The Power of Prayer), we see a parishioner, Betsy, who was placing her hope in her pastor. Maryann sensed the inappropriateness of this dynamic and was looking for a way to address Betsy’s misplaced hope.

Under the right conditions, this dynamic can occur with anyone. But it happens more often with clergy. People naturally tend to look for connections with those that they perceive as having higher status, as powerful, and as highly respected to enhance their self-esteem. Because our culture holds in high esteem those in religious vocations and the minister is generally the most conspicuous member of a congregation, it is no surprise that new visitors will try to meet the pastor personally (less so in very large churches), establish a connection, and gain the pastor’s attention with a word of appreciation or engaging comment.

Implicit Trust

Trust is the belief that a person is reliable, will meet expectations (often unspoken expectations), will conduct him- or herself according to a presumed code of standards common to the position, and will not harm another who is vulnerable or weaker. In many relationships, trust is earned over the course of time. However, certain relationships, such as that of doctor-patient, banker-investor, and clergy-parishioner, warrant an implicit trust based on the position and under the assumption that the character of the person in the position of power has been “certified” or endorsed by a governing body.

Implicit trust is closely associated with incarnated hope. Until recently, our culture has not only encouraged high respect for clergy, but also reinforced the idea that clergy persons merit implicit trust by virtue of their positions. Now, with the increasing media attention on moral failure, child sexual abuse, and incidents of glaring misconduct, implicit trust may not be quite as freely given, but it is still very much a force in vocational ministry. Consider how many people come to you and, in spite of limited relational history, pour out their troubles, speak their minds, and blurt out their histories. That is trust indeed!

Trust—especially implicit trust—endows pastors with power because it presumes that they will act in the best interests of their parishioners and reduces the likelihood that the pastors’ actions or motives will be questioned. Most people want to give others the benefit of the doubt. This is even more pronounced when it comes to parishioners’ relationships with their pastor. In the story of Joe (Special Friends), not even his wife appeared to question his whereabouts, seemingly because she assumed (trusted) he was working hard in his ministry.

Idealization

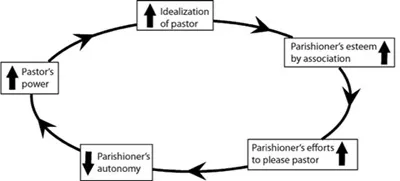

It is not uncommon for parishioners to place their pastor on a pedestal. People respect the position of spiritual leadership and feel the need to acknowledge the minister’s position; hence the titles used when addressing clergy: reverend, pastor, brother, father. Layering on top of this is the natural tendency for people to want their leader to be “perfect” (or close to perfect), solid, strong, unerring, and benevolent. If the leader is perfect, strong, and benevolent, the subjects can feel safe, secure, and cared for. People also gain significance and self-esteem for themselves by associating with someone perceived as powerful and “perfect.”

Pastors typically try to connect at least nominally with as many parishioners as possible. Parishioners feel esteemed by the pastor’s efforts to connect and relate, and when the pastor is idealized the parishioners’ increase in esteem is even greater. In essence, the greatness of the idealized person reflects back greatness on the person who is idealizing. Idealization creates a power differential because people naturally want to please someone they admire and believe to be a role model. They hope to garner notice, affirmation, and validation by the object of their admiration. In seeking to please, parishioners relinquish autonomy in exchange for feeling significant because of their connection with the powerful and “perfect” pastor: the greater the idealization, the greater the power differential and the greater the parishioners’ increase in esteem.

The dynamics of idealization are, for the most part, unconscious. This further contributes to the power differential: the less aware people are that they are idealizing the pastor, the less able they are to act autonomously and thoughtfully. They are less likely to recognize boundary problems when they do occur and less likely to enforce their own boundaries in the event that the pastor begins to encroach.

Figure 2. The Cycle of Idealization, Loss of Autonomy and Power

The increase in parishioners’ esteem is, of course, achieved by association, and is therefore not a real and durable esteem. Needless to say, if the pastor should do anything that even remotely resembles imperfection, the parishioners who idealize him or her will be dismayed and incensed. Their reaction is often exhibited as an offense to their moral sensibilities, but the greater offense is to their esteem, which was being bolstered by their association with someone they perceived as being “perfect.” Their idealization quickly turns to criticism and judgment when it has been determined that the pastor no longer meets the qualifications for idealization—he or she is no longer a fitting occupant for the alabaster pedestal. When Robert (The Ornament) could not meet the expectations of his parishioner, Sarah, she transformed her image of him from being the only one who could care enough for her to being uncaring, cold, and calloused.

Intimacy

In the course of ministry, pastors are often invited into the most private, intimate parts of their parishioners’...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- I. Foundations

- II. Boundary Building Blocks

- III. Boundary Applications in Ministry

- Notes