- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

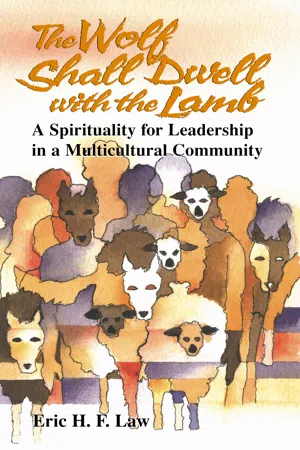

The Wolf Shall Dwell with the Lamb

About this book

This groundbreaking work explores how certain cultures consciously and unconsciously dominate in multicultural situations and what can be done about it.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Wolf Shall Dwell with the Lamb by Eric H F Law in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religious Institutions & Organizations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The “Peaceable Realm” as a Vision of an Ideal Multicultural Community

The wolf shall dwell with the lamb,

and the leopard shall lie down with the kid,

and the calf and the lion and the fatling together,

and a little child shall lead them.

The cow and the bear shall feed;

their young shall lie down together;

and the lion shall eat straw like the ox.

The sucking child shall play over the hole of the asp,

and the weaned child shall put his hand on the adder’s den.

They shall not hurt or destroy in all my holy mountain;

for the earth shall be full of the knowledge of the LORD

as the waters cover the sea.

and the leopard shall lie down with the kid,

and the calf and the lion and the fatling together,

and a little child shall lead them.

The cow and the bear shall feed;

their young shall lie down together;

and the lion shall eat straw like the ox.

The sucking child shall play over the hole of the asp,

and the weaned child shall put his hand on the adder’s den.

They shall not hurt or destroy in all my holy mountain;

for the earth shall be full of the knowledge of the LORD

as the waters cover the sea.

Isaiah 11:6–9, RSV

Ten years ago, I spent a semester in France studying the audiovisual communication of faith. For the first time I participated in a multicultural gathering in which three languages were used. The experienced instructors divided the participants into two major groups according to the languages that we spoke—an English group and a French/Spanish group. The two groups lived in separate housing facilities. We received instruction separately most of the time except for major lectures that were translated simultaneously. At the beginning of the program, we did many things together—field trips, discussions, planning, worship, and eating. The English group, of which I was a part, tended to enjoy these gatherings because most of the time we were doing activities that we liked.

As time went by, the two groups had fewer and fewer opportunities to gather except during lunch time and occasional large community celebrations. Finally, the English group questioned the instructors concerning the lack of opportunities to mingle with the French/Spanish group. The response was: “We decided not to put the two groups together anymore. We have had too many complaints from the French and Spanish group. They said that whenever the two groups were together, the English group always took control and the needs of the French/Spanish-speaking group were always ignored.” Upon hearing this, the English group, myself included, was taken totally by surprise. I had no idea that we were dominating and certainly was not conscious of the other group’s feeling. Some of us felt bad about it while others denied that they were dominating. Some tried to convince the French/Spanish group that they should not feel excluded.

This incident was a typical example of how cultural differences set up a frustrating power dynamic in a multicultural situation. Through my years of traveling and working with groups, I have asked people of all colors to share their multicultural group experiences with me. Eighty percent of them described the same frustration. Whenever two or three culturally diverse groups come together, the white English-speaking group most likely sets the agenda, does most of the talking and decision making, and, in some cases, feels guilty that the other ethnic groups do not participate in the decision making.

I observed the same scenario over and over again. For a long time, I felt totally powerless about changing the course of these encounters. I call it the “wolf and lamb” scenario. When a wolf is together with other wolves, everything is fine. When a lamb is together with other lambs, everything is safe and sound. But if you put a wolf and a lamb together, inevitably something bad is going to happen. Some people are so disheartened by it that they are giving up the idea of integration altogether. Many white English-speaking people enter a multicultural situation with dread and apprehension that the other might accuse them of domination and oppression. Many people of color stop accepting invitations to multicultural gatherings, knowing that they will be ignored and put down one more time and that the result will be a waste of their time.

If we stretch the analogy of the “wolf and lamb” scenario further, one might say that the cultures of the world are as numerous as the kinds of animals inhabiting this earth. Each culture has its own characteristics, values, and customs. Some are perceived as strong and some as weak. Some are more aggressive and some are considered passive and timid. People in one culture survive as individuals while people in another culture find their own liveliness as part of larger groupings. If cultures are analogous to the different animals, then Isaiah 11:6–9 becomes a vision of culturally diverse peoples living together in harmony and peace. This passage is known popularly as the “Peaceable Kingdom.” I prefer to call it the “Peaceable Realm.” For me, the word Kingdom has too many connotations of the hierarchical human system that the passage challenges. Realm may be a more neutral term. It connotes a state of being. It can also imply a philosophical essence, as in “realm” of thoughts.

In order for the animals to co-exist in this Peaceable Realm, very “unnatural” behaviors are required from all who are involved. How can a wolf, a leopard, or a lion not attack a lamb, a calf, or a child for food? At least our fairy tales taught us to believe that. How can a lamb or a calf not run when it sees a lion or a leopard coming close? How can a lion eat straw like an ox when a lion is known to be a meat eater? It goes against an animal’s “instinct” to be in this vision of the Peaceable Realm. Perhaps that is what is required of human beings if we are to live together peacefully with each other. Perhaps we have to go against the “instinct” of our cultures in order for us to stop replaying the fierce-devouring-the-small scenario of intercultural encounter. Perhaps, when all of us have learned how to do that, we may be able to regain our innocence like a child playing over the hole of the asp and putting her hand on the adder’s den and not being afraid anymore.

When I use the word culture in this context, I refer to ethnic culture—the values, beliefs, arts, food, customs, clothing, family and social organizations, and government of a given people in a given period. It is a known fact that ethnic cultures differ from each other to varying degrees. If all cultures were the same, I would not be writing this book. How do cultural differences come about? Here is a hypothesis that I discovered in a very useful book called Developing Intercultural Awareness. Before there were planes, boats, trains, television, movies and magazines, people lived in various parts of the world in isolated communities. Because of differences in climate and natural resources, people developed different ways to meet the basic necessities of life such as food, shelter, community, family, etc. These solutions to life’s basic necessities evolved into different cultures. These cultures are neither good nor bad. They are just different. However, because these cultures were developed in isolation, a person brought up in one particular culture, having never seen or experienced a different culture, believes that his or her culture’s way of doing things is the right way. This is called ethnocentricity. There is no problem when a person who was raised in one culture stays within that cultural group because everyone in the group knows, understands, and shares the same worldview. Problems arise when a person from one culture is put into another culture. Conflict becomes inevitable.1

It is helpful to look at culture in two parts: external and internal. External culture is the conscious part of culture. It is the part that we can see, taste, and hear. It consists of acknowledged beliefs and values. It is explicitly learned and can be easily changed. However, this constitutes only a small part of our culture. The major part is the internal part, which consists of the unconscious beliefs, thought patterns, values, and myths that affect everything we do and see. It is implicitly learned and is very hard to change. A good image that can help us understand this better is an iceberg.2 An iceberg has a small visible part above water and a very large and irregular part under the water. The part above water can represent external culture and the part under the surface can represent internal culture. What I mean by the “instinct” of our culture is this internal part that is not conscious and is very hard to change. Let’s examine the two parts of culture in more detail.

Most of the time, when we use the word culture, we mean the kinds of things that we see and hear—music, dance, food and art, etc. These are only the external cultural traits that are articulated and therefore observable. They are explicitly learned behaviors, knowledge, and beliefs. One is conscious of these external cultural traits and, therefore, they are easily changed. For example, I grew up in a Chinese household in which we ate only with chopsticks. Using chopsticks is definitely a learned behavior. Chinese were not born with chopsticks in their hands. Neither were Europeans born with a knife and fork in their hands. The objective of using chopsticks is very simple: to get food into your mouth so you won’t be hungry. The first time I went to a British restaurant, it was very puzzling to see the layout of forks, knives, spoons, glasses, and stacks of plates and bowls. My ethnocentric self thought: this is quite ridiculous when a pair of chopsticks and a rice bowl would be much easier, better, and faster. After my initial prejudiced reaction, I realized that the objective here was the same: to get food into your mouth. So with some practice, I learned very quickly the proper way to eat with knives and forks.

Let me offer another example. When I was a teenager in Hong Kong, I acquired a taste for American folk music. I liked it because it was simple music and easy to learn. I used to sing “This Land Is Your Land” in Hong Kong and had no idea what it all meant. When I immigrated to the United States in 1971, suddenly the music of Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, and Peter, Paul and Mary had a context. Within this context I consciously embraced many of the values of that era and began to write the same kind of music myself. As I evolved with the ’70s and ’80s, my philosophy, beliefs, and values changed and I did not stubbornly hold on to the ideals of the ’60s. Because I consciously adopted these values and beliefs, I usually could change them with ease after some reflection, research, or rationalization. I believe this flexibility came from my consciousness of embracing those values. I deliberately take up an idea and I can easily leave it behind. I would have had a more difficult struggle had I been born and raised in the ’60s in the United States, because many of these values and beliefs would be unconscious to me and, therefore, very hard to change.

However, external culture constitutes only a small part of our cultural iceberg. The larger part is the hidden internal culture that governs the way we think, perceive, and behave unconsciously. This is what I call the “instinct” of our cultures. Instinct as defined in Webster’s Dictionary is an “inborn tendency to behave in a way characteristic of a species: natural, unacquired response to stimuli….” The cultural environment in which we grew up shapes the way we behave and think. Implicit in this cultural environment are the cultural myths, values, beliefs, and thought patterns that influence our behavior and the way we perceive and respond to our surroundings. Most of the time, we are unconscious of their existence. They are implicitly learned and are very difficult to change. We are conditioned to react to our environment in particular ways that are not very different from an instinctual physical reaction to stimuli. When we feel the sting of a needle, we withdraw. In the same way, we interpret what we see according to these unconscious values and thought patterns and we respond in an instinctual way according to these beliefs and values regarding what is proper and right.

Internal culture is like the air we breathe. We need it to survive and make sense of the world that we live in, but we may not be conscious of it. If you put an object with both red and green designs in front of a red background, you will see only the green design. The red designs will blend into the background and become less noticeable. However, if you put the same object in front of a green background, you will see the red design much better and not notice the green design. Internal cultures are like these backgrounds. They influence the way we perceive our relationships and environment, often unconsciously. Internal cultural differences, then, are like the difference between the red and the green backgrounds. It is not a matter of different ways of eating or different clothing or languages. It is more a matter of perceptions and feelings. The same event may be perceived very differently by two culturally different persons because the two different internal cultures highlight different parts of the same incident. This internal, unconscious part of culture constitutes a much larger part of our culture. To discover the unconscious, implicit part of our culture is a lifelong process. Some of us go through life like a fish in the stream and never know that we are living in water.

As a Chinese American with a somewhat complicated cultural makeup, I still surprise myself when I discover a new aspect of my internal culture. For example, one of my “instinctual” reactions to conflict is to be silent. It took me a long time to recognize this internal cultural trait. Every internal cultural trait has a value behind it. To be culturally sensitive is to recognize these values in ourselves and in others. After much reflection and help from friends and spiritual directors, I discovered that, growing up as the youngest child in a Chinese family, I used silence as a way to protect myself. Silence in my family is a form of protest. It still works for me today but only in the context of my family. I was eating dinner and conversing freely with my parents one evening last year. In the middle of the interchange, my father said, “Eric, I think you should go to medical school and become a doctor. Look at Mr. Wong’s son. He was a little guy then, but he made it. He is a doctor now. If he can do it, you can too.”

I had not heard my father mention medical school since I was ordained, so I was quite disturbed by what he was saying at this stage of my life. My ego was bruised. Here I was, thirty-four years old, an ordained Episcopal priest, with two degrees. I traveled all over the country to teach, consult, and give workshops. I composed music and had put out three recordings. And my father wanted me to be a doctor! While I was steaming over what he said, I grew silent. I could get mad and confront him. I could stand up and walk away, but I simply stopped talking. My mother immediately sensed my protest. She, in her gentle way, said, “Your father thinks you are still a little boy sometimes.” Then to my father she said, “I don’t think being a doctor is so great anymore. In this country, you can go broke paying the malpractice insurance. In Hong Kong, it’s a different story. At least you get respect. Here you don’t even get respect. At the blink of an eye, you get sued.” That took care of it. My father never talked about medical school again. I at that moment resumed my conversation with my parents on another topic. My silence was interpreted correctly as a protest against my father’s lack of sensitivity.

However, I was not conscious of this implicit cultural trait for a long time. In a white English-speaking environment, when I disagreed with what was going on, all I knew was that people ignored me. I could not understand why they did not read my message of disapproval. I did not realize that they probably interpreted my silence as consent, indifference, or incompetence. Even though I am conscious of this now, my initial reaction to most conflict is still silence. This has been an implicit value for me for a long time, and it is very hard to change. However, I have learned to recognize this internal cultural trait and to take positive steps to determine the appropriateness of this behavior. For example, if I am in a first-generation Chinese environment, silence is still an appropriate behavior to communicate dissent. But if I am in a white English-speaking situation, I must recognize that silence will be misinterpreted and I must find ways to verbalize my disagreement.

Cultural clashes do not happen on the external, conscious cultural level. We can easily change behaviors based on conscious values and beliefs in order to adapt and accommodate to the situation. We can even modify our acknowledged beliefs and values with some intellectual reasoning and reflection. Most cultural clashes happen on the internal unconscious level—on the instinctual level where the parties involved are not even conscious of why they feel and react the way they do. Since each person thinks only in her own thought pattern, she cannot even understand why the others do not perceive things the way she does. It is like two icebergs hitting each other under the water. On the surface they appear to be at a safe distance from each other. This communication breakdown creates a mutual animosity, causing a need to protect oneself. This defense usually comes in the form of putting down the other or assuming one’s own culture is superior.3

To be interculturally sensitive, we need to examine the internal instinctual part of our own culture. This means revealing unconscious values and thought patterns so that we will not simply react from our cultural instinct. The more we learn about our internal culture, the more we are aware of how our cultural values and thought patterns differ from others. Knowing this difference will help us make self-adjustments in order to live peacefully with people from other cultures. A lion needs to know that its predatory instinct can hurt the calf and therefore must temper it. A lion might even become a vegetarian for a while in order to live in the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Also by Eric H. F. Law

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 - The “Peaceable Realm” as a Vision of an Ideal Multicultural Community

- Chapter 2 - What Makes a Lamb Different from a Wolf? Understanding Cultural Differences in the Perception of Power

- Chapter 3 - Differences in the Perception of Power and Their Consequences for Leadership

- Chapter 4 - What Does the Bible Say to the Powerful and the Powerless?

- Chapter 5 - A Fresh Look at Pentecost as the Beginning of a Multicultural Church Community

- Chapter 6 - Who Has Power and Who Doesn’t? Power Analysis, an Essential Skill for Leadership in a Multicultural Community

- Chapter 7 - The Wolves Lie Down with the Lambs

- Chapter 8 - Living Out the Fullness of the Gospel in the Peaceable Realm

- Chapter 9 - Mutual Invitation as Mutual Empowerment

- Chapter 10 - Media as Means of Distributing Power

- Chapter 11 - Liturgy as Spiritual Discipline for Leadership in a Multicultural Community

- Appendix A - Mutual Invitation

- Appendix B - Using Photolanguage in Small Group Communication

- Appendix C - Community Bible Study