- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Teaching the Bible in the Church

About this book

This interdisciplinary conversation combines educational theory with Bible scholarship to help teachers of the Bible move beyond conveying information to revealing the transformative power of the scripture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Teaching the Bible in the Church by John Bracke,Karen Tye in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Biblical Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Biblical Studies 1

Teaching the Bible: How We Learn

It was the first night of a workshop on teaching the Bible in the church that we were leading for a local congregation. The participants were church school teachers of children and adults and several interested church members. In order to illustrate some of the material we were presenting, we asked the participants to read and think about Psalm 23. After some discussion of early memories regarding this psalm, we invited participants to sit back, close their eyes, and listen to a musical representation of this text. The room became quiet, and slowly the sounds of a beautiful Gregorian-like chant filled the air and the familiar words began: “The Lord is my Shepherd, I have all I need, She makes me lie down in green meadows, Beside the still waters, She will lead.”1 We could feel the mood in the room shift. “She restores my soul, She rights my wrongs, She leads me in a path of good things, And fills my heart with songs.” It was almost as though the participants were holding their collective breath. What was this?

Even though I walk, through a dark and dreary land,

There is nothing that can shake me,

She has said she won’t forsake me,

I’m in her hand.

There is nothing that can shake me,

She has said she won’t forsake me,

I’m in her hand.

She sets a table before me, in the presence of my foes

She anoints my head with oil,

And my cup overflows.

She anoints my head with oil,

And my cup overflows.

Surely, surely goodness and kindness will follow me,

All the days of my life,

And I will live in her house,

Forever, forever and ever.

All the days of my life,

And I will live in her house,

Forever, forever and ever.

As the music came to an end, the quiet was absolute. We paused for a moment, then asked for people’s responses. Slowly they came. Some were angry—“I don’t like that interpretation. The language doesn’t speak to me!” “God isn’t a She!” “I had a hard time listening.” Others were deeply moved, but for different reasons. One person said that the beauty of the music held her attention. Another woman said that it was a deeply emotional experience for her, that she felt a real connection with the psalm because of the feminine language. When we commented that Bobby McFerrin wrote this version of Psalm 23 for his mother and dedicated it to her, we saw faces light up with recognition and understanding. This information seemed to help make a connection with this representation of the text, especially for those who were angry or feeling some discomfort.

In witnessing this encounter, we became aware that we were watching learning take place, watching the process by which people struggle to know, understand, and make meaning of a biblical text, with all its accompanying complexities and ambiguities. Understanding something about this process we call learning is foundational to our work as teachers of the Bible in the church. In this chapter we want to discuss some of the primary factors that we have discovered are key to how people learn. We believe this information is vital if we are to teach the Bible in ways that enable people to learn, make meaning, and hopefully be transformed. Although we cannot engage in an exhaustive look at learning, which would take volumes, we do want to consider some of the basics about learning that have proven helpful to our own work in teaching the Bible. These basics include (1) the brain and how it works, (2) memory and how it is formed, and (3) the role of learning styles and multiple intelligences in the learning process.

The Brain and How It Works

As we observed the participants in our workshop on teaching the Bible that evening, we were observing the human brain at work. In fact, it is simply impossible to talk about learning without beginning with the brain. However, we need to hear a word of caution. Although neuroscientists are making amazing discoveries regarding how the brain works, there is still so much we do not know. Therefore, we need to approach the following discussion with a certain sense of humility, open to the new discoveries that are yet to come. That does not mean, however, that we don’t have several important insights already at hand. As Eric Jensen says, although we do not yet have an “inclusive, coherent model of how the brain works,” we do know enough to rethink and reshape how we teach and learn.2 What are some important “facts” about the brain that we need to know?

First, the human brain is “the best organized, most functional three pounds of matter in the known universe.”3 As human beings, we have more than enough brain matter for the work of learning! Our brains have more than 100 billion neurons, or nerve cells, and these neurons are key to learning. In fact, neuroscientists define learning as “two neurons communicating with each other.”4 Neurons have “learned” when one neuron sends a message and another neuron receives that message. In other words, learning occurs when two neurons communicate. They make a connection. But it is more than just two single neurons. Several neurons become involved in the communication, and what is called a “neural network” is formed. It is the engagement of these neural networks that is central to learning.

The key here is to continually engage these connections. As Marilee Sprenger points out, “The more frequently a neural network is accessed, the stronger it becomes.”5 The more we use the connections that have been made in a neural network, the more firmly set that learning becomes. Let’s use an example. A child sees a cat for the first time. Her mother points to the cat and says “cat.” The child attempts to repeat the word. At that moment her brain makes a connection. A few neurons are talking about “cats.” If the cat meows, the child makes a connection that this object called a cat makes a sound like this. The next time she sees a cat and hears it meow, her brain will make these same connections—cat and meow. Each time the child encounters a cat and hears it meow, the neurons become more efficient at connecting, and the message that this is a cat and it meows travels more swiftly through the neural network. As time goes on, the child will add more connections to the neural network regarding cats; the more this network is used (in other words, the more the child encounters cats), the stronger the connections will be.

Let’s return to our participants in the workshop. When we first asked these folks to talk about their early memories and experiences with Psalm 23, we were inviting them to access their neural networks regarding this psalm. Many of them had had several encounters with this very familiar psalm, and therefore some strong connections were already in place. That’s how neural networks work. The more we return to a familiar text and read it, hear it in sermons, sing it in songs, encounter it in a variety of settings (funerals are a favorite setting for Psalm 23), the stronger the learning with regard to that text.

Scientists call this strengthening of the neural networks “neural branching.” The more we engage an object, experience, or idea, the more connections or “branches” are formed between neurons and the easier it is for that network to be accessed and used. The opposite is also true. When a neural connection is not used, when we no longer have some experiences or encounter certain objects or read about certain subjects or exhibit certain behaviors, the connection is lost. As Sprenger says, “Each day the brain prunes some neuronal connections because of lack of use.”6

This knowledge that the brain engages in both neural pruning and branching as it makes connections carries an important implication for our work as teachers of the Bible. We can either teach for branching or teach for pruning. We teach for neural branching by helping our students make connections with the material and doing this over and over again. The first time a child hears a Bible story, a connection is formed. A neural network begins to take shape. Whether that network stays in place and the knowledge becomes a part of long-term memory depends a great deal on whether the network is accessed again and again. This is why it is important to focus on a single story and to tell that story over and over again in a variety of ways. Jumping from story to story too quickly, as sometimes happens in some church school curricula, does not aid in the development of neural branching and generally leads to little of that story being retained. By not using the connections again and again, we engage in neural pruning. If our participants in the workshop had only heard Psalm 23 a few times in their lives, their memories of this psalm would be weak. But because of its frequent use in a variety of settings, many of those participants had strong memories, strong neural networks with regard to this particular text.

The knowledge that the brain engages in neural branching and pruning as a part of the learning process leads to another fact we need to know about the brain. Scientists are now talking about the “plasticity” of the brain,7 referring to the brain’s ability to grow and change. We used to think that the brain was pretty well “fixed” by a young age, usually around the age of five, but research is now indicating that this is simply not true. The brain continues to adapt and change throughout our lifetime. We actually change the physical structure of the brain through the experiences we have, meaning that we engage the brain’s neural branching and pruning capabilities through our experiences. The old adage “You can’t teach an old dog new tricks” is just not true from a brain perspective. We are capable of continuing to learn, of shaping our neural networks, throughout our lives.

We were offering an opportunity for new learning when we played the McFerrin interpretation of Psalm 23 for our workshop participants. Trusting in the brain’s plasticity and that new branching could occur, we sought to expand our participants’ understandings of Psalm 23 and its meanings for their lives by offering a new experience that held the possibility that a new branch would be formed in their neural network regarding this psalm. We sought to help this connection in a couple of ways. First, by asking participants to share their memories of this psalm, we were activating the networks already in place. Second, in placing this new interpretation in a context by sharing the origins of McFerrin’s work as a tribute to his mother, we were providing a way to connect to this different translation with which participants might identify. Our own experiences of mothers as those who shepherd us, love us, and steadfastly stand by us open a neural branching between Psalm 23 and mothers that might deepen our insight regarding the nature of the Lord, or God, and strengthen our neural network for this text.

A third fact about the brain that is important for teachers of the Bible to know is in regard to certain structures of the brain that play a significant role in learning. Our purpose here is not to go into great detail regarding these structures and their specific biology but to help us understand how the brain engages in the work of learning and creating memory. We will say more about memory itself in a later section of this chapter.

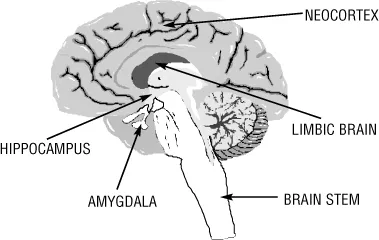

Located in a central part of the brain, called by some the limbic brain,8 are two structures that are crucial to learning and memory. These are the hippocampus and the amygdala (see figure 1). The hippocampus sorts and files the factual information that the brain learns. The amygdala sorts and files emotional information. To understand the importance of these two brain structures, we need to look briefly at how the brain processes information.

Information comes into our brain through our five senses and is first filtered through the brain stem. It is then sent to the thalamus, the brain structure that first sorts information. If the information is visual, the thalamus sends it to the visual part of the cortex, where it is initially processed; if it is auditory, it sends it to the auditory cortex, and so on. The cerebral cortex also sorts through the information, relaying it to the hippocampus for cataloging and filing. The hippocampus does not actually house the information itself. It sends it on for permanent placement in other storage places in the brain and the body.

Figure 1

The hippocampus plays an important role in determining what is retained and what is forgotten. The senses continually flood the brain with information, some of it vital but much of it unimportant. You don’t need to remember the face of everyone you pass on the street, but you do want to recognize the faces of your spouse and children! To prevent an information overload that would accompany having to remember too much, the hippocampus sifts through the barrage of incoming information from the cortex and picks out what to store and what to discard. In other words, the hippocampus serves as a central clearinghouse, deciding what information will be placed in long-term memory and helping to retrieve it when called upon.

The question that comes to the fore, then, is how the hippocampus decides what is worth storing—in other words, what is worth learning and remembering. There is growing evidence that two primary factors shape the hippocampus’s decision to store information for future access. The first is whether the information has emotional significance. The amygdala is the key player in this decision. The second factor is whether the new information relates to something we already know. Put another way, “If information is not meaningful or allowed to form patterns in the brain, it will be lost.”9

Two important implications for teaching the Bible emerge from this information about how the brain works. The first of these is that emotion plays a significant role in learning. We ignore it at our peril! As Robert Sylwester says, “The best teachers know that kids learn more readily when they are emotionally involved in the lesson because emotion drives attention, which drives learning and memory. It’s biologically impossible to learn anything that you’re not paying attention to.”10 The relationship between attention and emotion is critical. Our choice to play McFerrin’s interpretation of Psalm 23 for our workshop participants was a deliberate one because we knew it would evoke an emotional response from listeners. Not everyone felt the same emotion, but they all had a felt response and were attentive to what was going on. But it wasn’t enough just to evoke an emotional connection and have their attention. We also needed to do something with that attention, to engage that emotional response in a positive and helpful way. This leads to the second implication for teaching the Bible that emerges from our understanding of the work of the hippocampus. This is the importance of teaching for connections. As mentioned earlier, the brain is naturally a connecting organism. It engages in neural branching as it processes information. We can help it in this process, and help the hippocampus do its work of sorting information, if we provide some connections between new information and that which is already in place. It is like knowing what file folders are already in the files before we start to put new material in them. We sought to get a feel for the connections that were already in place for our participants by asking them to reflect on early memories they had of Psalm 23: where they had first heard it, some of the important images it evoked for them, and what associations they had with it. In addition, this helped the participants bring these connections into conscious memory.

But we also wanted to help make connections with this new expression of the psalm. To do so, we drew on the context out of which McFerrin’s interpretation came—a tribute to his mother. Participants were invited to think about why McFerrin would identify this psalm with his mother, and we found ourselves in the midst of a rich discussion about the similarities between the qualities of a good mother and the qualities of the shepherd in the psalm. It was a short step to begin to think of our images of God and how God might be like a mother. To our mostly city-dwell...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 - Teaching the Bible: How We Learn

- Chapter 2 - Teaching the Bible: How We Teach

- Chapter 3 - Teaching the Bible: An Intercultural Education Experience

- Chapter 4 - Teaching the Bible: Issues of Interpretation

- Chapter 5 - Teaching the Bible: Putting It All Together

- Women’s Bible Study

- Notes