eBook - ePub

The Stone-Campbell Movement

A Global Histroy

- 488 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Stone-Campbell Movement

A Global Histroy

About this book

The Stone-Campbell Movement: A Global History tells the story of Christians from around the globe and across time who have sought to witness faithfully to the gospel of reconciliation. Transcending theological differences by drawing from all the major streams of the movement, this foundational book documents the movement's humble beginnings on the American frontier and growth into international churches of the twenty-first century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Stone-Campbell Movement by Douglas A. Foster,D. Newell Williams, Douglas A. Foster, D. Newell Williams in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & History of Christianity. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

History of Christianity1

Emergence of the Stone-Campbell Movement

The Stone-Campbell Movement began with the union in the 1830s of two North American groups: the Christians led by Barton W. Stone, and the Reformers led by Thomas and Alexander Campbell. Influenced by a host of people, ideas, and events, both groups affirmed that Christian unity was critical to the evangelization of the world and the in-breaking of Christ’s earthly reign of peace and justice. The founders of both groups were identified with Presbyterian denominations—Stone in the United States, and the Campbells in Northern Ireland. Also, each group attracted significant numbers of Baptists. Yet despite these similarities, there were significant differences between the two groups.

Christians

The Christians emerged from the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, a body profoundly shaped by colonial revivalism. The revivals that appeared among New Jersey Presbyterians in the 1720s proved controversial. The central issue was the revivalists’ insistence that religion was a “sensible thing,” an experience of the work of the Holy Spirit, and not merely a matter of believing the right doctrines and living a moral life. Matters came to a head in 1741 when the anti-revival Old Light party expelled the pro-revival New Light party from the Synod of Philadelphia. Following the division, the New Lights constituted themselves as the Synod of New York and continued to grow, while the Old Lights declined. In 1758, the two parties reunited largely on New Light terms.1 The Presbyterian Church from which the Christians emerged in the early nineteenth century was the church formed by the reunion of 1758.

The Old Northwest

Barton Warren Stone (1772-1844) joined this church while studying at the classical academy of Presbyterian minister David Caldwell in Guilford County, North Carolina. When he entered the academy in January 1790, a neighboring Presbyterian pastor, James McGready, was leading a revival among the fifty or so students of the academy. McGready stood squarely in the tradition of the colonial awakening, preaching that human beings were created to know and enjoy God. Having lost this capacity because of the first sin, however, they sought happiness through the satisfaction of their “animal nature,” the possession of “riches” and “honors,” and a “religion of external duties” which they thought appeased God who remained unknown and unloved. Yet none of these substitutes could satisfy their longings for happiness. At death they would be separated from God eternally and suffer torments beyond human comprehension.2

McGready urged that salvation delivered God’s elect from future punishment and enabled them to experience in this life the happiness for which they were created—the happiness of knowing and enjoying God. Heaven was a continuation of this happiness. Salvation through faith in Jesus Christ caused the sinner to fall in love with God and come to Christ, both for pardon from the penalty of sin and release from its power. Though this faith was a gift from God, only sinners who applied to Christ—who sought faith—could have assurance of receiving it. One applied to Christ by using the “means of grace,” which included withdrawing from distracting activities such as dancing and playing cards, asking God to change one’s heart, and meditating on the horrors of sin and the full and free salvation in Jesus Christ.

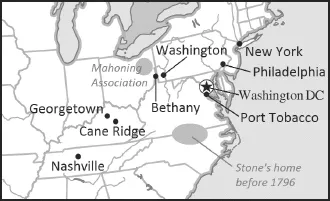

Stone had entered Caldwell’s academy with the intention of pursuing a career in law, a career he believed would enable him to attain the wealth, status, and pleasures that, according to the popular literature of his day, would bring him happiness. Born December 24, 1772, near Port Tobacco, Maryland, he had grown up in an Anglican family long accustomed to wealth and social standing. His father, John Stone, whose holdings in land and sixteen enslaved Africans identified the family as upper middle class, had died when Barton was three. Four years later, in the midst of the American Revolution, his mother Mary had moved the family to Pittsylvania County, Virginia, where they had continued to identify with the Church of England.

Though Stone tried to ignore the revival, he could not deny that the converts seemed to enjoy a happiness he did not know. Hearing McGready preach, he resolved to seek the gift of faith. In keeping with Presbyterian teaching of the time, his period of seeking faith lasted a full year. At one point he despaired of ever receiving it. He reported that he received the faith he sought through a sermon delivered by McGready’s colleague, William Hodge.

With much animation, and with many tears, he spoke of the love of God to sinners, and of what that love had done for sinners. My heart warmed with love for that lovely character described... My mind was absorbed in the doctrine—to me it appeared new.

According to revivalist Presbyterians, to find one’s heart “warmed” with love to God and to find something “new” in the preaching of what God had done for sinners through Jesus Christ were signs of faith. Stone reported that the truth of God’s love triumphed, and that he fell at the feet of Christ, “a willing subject.”3

Following his conversion, Stone felt a call to preach the gospel. Completing his studies at Caldwell’s academy, he became a candidate for the ministry in the Orange Presbytery of North Carolina in spring 1793. This was the beginning of a struggle, which, though it would not prevent him from being ordained as a Presbyterian minister, would ultimately lead him to separate from the Presbyterian Church—a struggle between Presbyterian doctrine and Enlightenment reason.

The Presbytery directed Stone and former classmate Samuel Holmes to prepare for an examination on the doctrine of the Trinity by reading a work by the seventeenth century Dutch Reformed theologian, Herman Witsius.4 Stone remembered that

Witsius would first prove that there was but one God, and then that there were three persons in this one God, the Father, Son and Holy Ghost—that the Father was unbegotten—the Son eternally begotten, and the Holy Ghost eternally proceeding from the Father and the Son—that it was idolatry to worship more Gods than one, and yet equal worship must be given to the Father, the Son, and Holy Ghost.

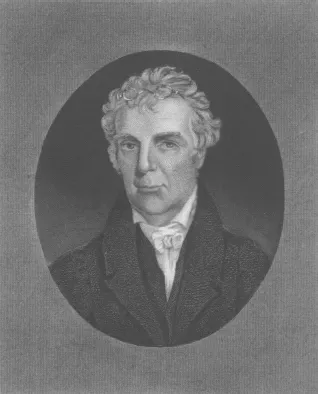

Engraving of Barton W. Stone from a portrait by Alexander Bradford who lived in Georgetown, Kentucky, in the 1820s. It appeared in the Biography of Elder Barton Warren Stone Written by Himself, With Additions and Reflections by Elder John Rogers, published in 1847.

Previously Stone had prayed to the Son without fear of idolatry or concern for equal worship to the members of the Trinity. The result of his effort to follow Witsius’ Trinitarian teaching was that he no longer knew how to pray, which greatly diminished the enjoyment of God he had known since his conversion. “Till now,” he wrote, “secret prayer and meditation had been my delightful employ. It was a heaven on earth to approach my God, and Saviour; but now this heavenly exercise was checked, and gloominess and fear filled my troubled mind.” When he and Holmes discovered that each was having the same problem, they stopped studying Witsius, convinced that his text obscured rather than enlightened the truth and had disrupted their spiritual development.5

Like other Americans of the Revolutionary generation, Stone had been influenced by the Enlightenment dictum of John Locke that propositions inconsistent with clear and distinct ideas were “contrary to reason.” To Stone, the idea that there was more than one God, which he found implied in Witsius’ teaching that equal worship must be given to the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, was inconsistent with the clear and distinct idea that there is one God. Not considering the possibility of holding in tension seemingly contradictory propositions, Stone concluded that Witsius’ treatment was unintelligible.6

Witsius’ work, however, was not the only treatment of the doctrine of the Trinity. Henry Patillo (1726-1801), a respected member of the Orange Presbytery, championed the views of Isaac Watts (1674-1748) who had been influenced by the Enlightenment. Watts argued that the scriptural doctrine of the Trinity was not contrary to reason. To be sure, the idea that “three Gods are one God, or three persons are one person” was contrary to reason. The Scriptures, according to Watts, taught that “the same true Godhead belongs to the Father, Son and Spirit, and… that the Father, Son and Spirit, are three distinct agents or principles of action, as may reasonably be called persons.” Thus, to say “the Father is God, the Son is God, and the Spirit is God” was not contrary to the proposition that there is one God.7

As to the proper worship owed to the members of the Trinity, Watts asserted that the Scriptures revealed all that was necessary. One could be sure that it was proper to worship Father, Son, and Spirit because Scripture clearly reveals that they share in the divine nature or godhead, implying that we should worship the members of the Trinity with an eye to the specific place, work, and character Scripture attributes to each.8

Stone and Holmes obtained Watts’ “treatise” and accepted his views.9 Stone’s struggles with Presbyterian doctrine and Enlightenment reason, however, did not end with his discovery of Watts’ treatise. By spring 1794, he had decided to pursue some other calling. “My mind,” he wrote, “was embarrassed with many abstruse doctrines, which I admitted as true; yet could not satisfactorily reconcile with others which were plainly taught in the Bible.” As before, when Stone had struggled with the doctrine of the Trinity, his intellectual difficulties affected his devotion: “Having been so long engaged and confined to the study of systematic divinity from the Calvinistic mould, my zeal, comfort, and spiritual life became considerably abated.”10

Yet he could not shake his call to ministry. After teaching for a time in Georgia, he returned to North Carolina in spring 1796, successfully completed his theological examinations, and received a license from the Orange Presbytery to preach the gospel as a probationer. He had not, however, overcome his earlier difficulties with Calvinist theology. He admitted that during his first years of ministry, he accepted the Calvinist doctrine of predestination as true but beyond human understanding. As a result, he avoided it in preaching.11 David Caldwell had advised just such a course of action to another of his students, Samuel McAdow, who later became a leader of the Cumberland Presbyterians.12

In late 1797, the Presbyterian congregations at Cane Ridge and Concord in central Kentucky invited Stone to serve as a probationer. The following spring, he received a call through the Transylvania Presbytery to become pastor of the two congregations. October 4, 1798, was set for his ordination.13 Knowing that he would be required to “sincerely receive and adopt” the Westminster Confession of Faith as “containing the system of doctrine taught in the Holy Scriptures,” he undertook a careful re-examination of the document. This resulted in an even greater crisis than before. He could not believe the doctrine of the Trinity as expressed in the Confession. Furthermore, he had great doubts about the Confession’s teaching on predestination. Convinced that God gives faith, he struggled to understand how a God who loves sinners could give faith to some by a special work of the Spirit and condemn others for not believing.14 In Lockean terms, the clear and distinct idea was that God loves sinners and desires that they come to faith.

As the day of his ordination at the Cane Ridge meeting house arrived, Stone informed James Blythe (1765-1842) and Robert Marshall (1760-1833), two leaders of the Presbytery, of his difficulties with the Confession’s teaching on the Trinity. He did not, however, share his doubts regarding the doctrine of predestination. The Adopting Act of 1729 had allowed Presbyterian ordination of ministerial candidates who would only partially subscribe to the Confession of Faith if, in the view of the presbytery, the candidate’s objections to the Confession concerned “non-essentials.” Though later repealed by the Old Light Synod of Philadelphia, the Adopting Act’s ideas continued to guide many Presbyterians.

Failing to relieve Stone of his difficulties with the Confession, Blythe and Marshall asked him how far he would be willing to adopt it. Stone answered that he would be willing to do so as far as he saw it consistent with the Word of God. Blythe and Marshall indicated that Stone’s partial subscription was sufficient, and the ordination proceeded.15

Meanwhile, a revival had begun in Logan County, Kentucky, forty miles north of Nashville, Tennessee, that would help Stone resolve his difficulties with the question of how a God who loved sinners could give faith to some and condemn others for not having it. James McGready, whose preaching had fueled the revival at Caldwell’s Academy, had become pastor in 1796 of three congregations named after Logan County rivers—Red, Muddy, and Gasper. By spring 1797, a brief awakening had occurred at the Gasper River church. During summer and fall 1798, awakenings had begun at the Gasper, Muddy, and Red River congregations.

These revivals grew out of sacramental meetings—a Scottish tradition widely adopted by eighteenth-century American Presbyterians. On Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, ministers from several congregations preached on themes related to conversion and the Christian life. On Su...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Contributors

- Introduction: A New History of the Stone-Campbell Movement

- 1. Emergence of the Stone-Campbell Movement

- 2. Developments in the United States to 1866

- 3. Growth of African American Institutions to 1920

- 4. The Expanding Role of Women in the United States, 1874-1920

- 5. Divisions in North America: The Emergence of the Churches of Christ and the Disciples of Christ

- 6. Origins and Developments in the United Kingdom and British Dominions to the 1920s

- 7. The Expansion of World Missions, 1874-1929

- 8. Churches of Christ: Consolidation and Complexity

- 9. Disciples of Christ: Cooperation and Division

- 10. The Emergence of Christian Churches/Churches of Christ

- 11. Responses to United States Social Change, 1960s–2011

- 12. Significant Theological & Institutional Shifts in the United States

- 13. Developments in the United Kingdom and British Commonwealth

- 14. The Stone-Campbell Movement in Asia Since the 1920s

- 15. The Stone-Campbell Movement in Latin America and the Caribbean Since the 1920s

- 16. The Stone-Campbell Movement in Africa Since the 1920s

- 17. The Stone-Campbell Movement in Europe Since the 1920s

- 18. The Quest for Unity

- Conclusion: Toward a Stone-Campbell Identity

- Notes

- Index