![]()

1 | START SMALL, THINK BIG

Takeaways

• To work effectively for change we need to understand others’ narratives, from their point of view, as well as our own.

• Our values and vision are crucial, if we are to know why we are doing this work and avoid being co-opted by the powers that be.

• Conflict, as distinct from violence, lies at the heart of all social and political change.

• Nonviolence is often more effective than violence in achieving lasting change.

• Sometimes we need to be subversive: be “technical” if that is what our sponsors and managers expect us to do, and then quietly go further and be “transformative” for deeper change.

Summary

This chapter suggests that knowing where we stand, and what we stand for, is key to taking any meaningful action. It sets out an inclusive way of understanding the broad context in which we find ourselves, describes some of the main options available to us when we are working for change, and considers some of the implications. The chapter suggests a range of ways to work for deeper change, while fulfilling organisational demands that may seem to exclude these.

1. Exploring our differing perspectives on the world

Who are we, readers of this book? We may imagine ourselves with any number of “hats”.

Perhaps you are a volunteer, on the staff or a member of an organisation that works on development, rights, humanitarian assistance, environmental issues, governance, healing, reconciliation, peace, community organising …

Or you might be a teacher, doctor or nurse, government worker, journalist, student …

Maybe you are a trader, factory worker, entrepreneur, farmer, civil servant, politician or a member or leader of your faith community.

Or perhaps you are a police officer or member of the armed forces curious to learn more.

You may be an outsider – an experienced practitioner wanting to help others work on their own conflict situations, or an insider, involved directly in a conflict and wanting to find new ways to deal with it.

We may therefore be people with different aims and values, different education and lifestyles. We don’t easily see the connections between one another and our different fields. We can often see each other as rivals for public profile or resources, if not actually “the enemy”, rather than as potential allies working on different aspects of a particular goal or vision: to help build a better community, a better country, a better world.

But what do we actually aim to do when we try to make the world a better place? Here our ideas naturally diverge, as our perspectives on the world are likely to be very different.

• Some of us think that the current world situation is more or less under control, regulated to the extent possible by market forces and national governments.

• Others think capitalism is in deep crisis. Current economic models are a source of exclusion and conflict. Inequality is growing within and across nations accompanied by an alarming rise in authoritarianism and nationalism, perhaps as a reaction to globalisation.

• Some argue that we are experiencing the aftermath of empire and colonialism.

• For a growing number the biggest threat to the planet is climate change. We urgently need realistic alternative models to the self-destructive way in which world society is currently organised, and to build the political will for change.

• Others see our problems as caused by overpopulation. If we can control population growth, the consumption of global resources will reduce, urbanisation will become more manageable and violent conflict will decrease.

• For yet others, a key global challenge is caused by a mix of Western governments and corporations, who in their quest for global wealth and power are militarising the globe and driving the world to more or less permanent war.

• Some are more hopeful altogether. Wars are gradually reducing, and nonviolent movements are proving more effective than violent ones in achieving constructive change. There is a growth in spiritual awareness and global consciousness. Change is coming, gradually but irresistibly.

People with variations on these, and other points of view, might all be working for a better world, as they see it, where people are living peacefully. So, are these views all equally valid? Even those views people have held unquestioned for many years, or those which fit readily into prevailing norms of class, culture or tribe?

Most of us tend to have a default position, which is largely unspoken. It has emerged as a result of our upbringing and life circumstances, with some explicit or implicit influences. We like to keep it safe and unchallenged. We tend to socialise with people who hold similar views, and choose media that support our values. But in order to understand ourselves and others better, and thus be more effective, we might want to reflect on what evidence there is for our stance, and how far our own behaviour corresponds with the worldview we take.

If we differ on our perspectives, we also differ on how to make change happen too. Some of us think that a bottom-up, empowerment approach is the most effective, while others prefer focusing on reform at the level of laws, policies and procedures. Some of us think that the best we can do is to make the current system work better, while others want more revolutionary system change. Some of us prefer to work through protest, conflict and confrontation, while others are more focused on finding ways to cooperate with those we oppose, and to influence them that way. Some of us believe that identifying and supporting enlightened leaders (being good followers) is the way to go, while others mistrust in their bones, leaders with a public profile.

And some of us, including the authors of this book, feel that a multi-pronged approach is probably the most effective, combining protest and policy work. In movements for change there are many different actors adopting different approaches, but united in a common goal and set of values. While we know there are differences, successful change depends on an ability to see where our objectives overlap, even with very unlikely groups, and work together on these. The only absolute barrier to cooperation, perhaps, is with those groups who assert the absolute nature of their views and beliefs, and deny the right of others to differ.

Questions for reflection

• Can you describe, or draw on paper, your viewpoint about how the world does or doesn’t work? Is your view close to one of those we have listed?

• Ask someone else to listen to you, and challenge some of what you say. Enjoy the discussion. Notice where you feel unsure or anxious.

• What evidence are your views based on? How much do they conform to those of your family, your culture, your religion, education or the media? Is this enough, to constitute your value-base for life and action? So what?

• Try to listen to other, very different narratives. (Listening does not mean agreeing.) What can you learn about your own perspective from doing this?

• What groups can you think of who might possibly be open to collaboration with you, although they seem to be very different, and maybe even in partial opposition to you?

2. A conflict transformation perspective

Fortunately, we don’t need to have consensus on a single worldview within our communities and with our colleagues. But we do need to be as clear as we can on the values we stand for, so we can work creatively with the differences and build strategies which meet all our needs. In addition, clarity about our values can help us understand better who could be our long-term allies, who we might work with for a short part of our journey, and who is aiming for another kind of world altogether, more or less incompatible with our vision.

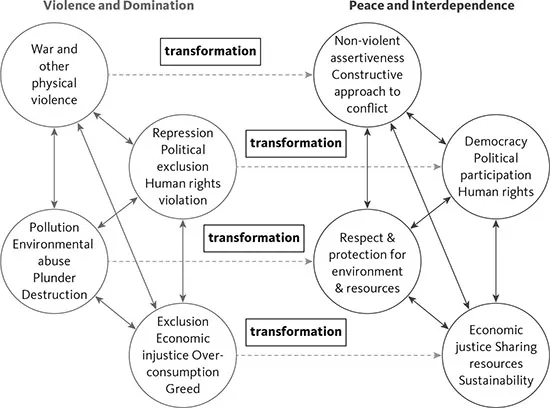

Figure 1.11 shows in simplified form the main threats and challenges facing the planet. On the one hand there are key interlinked areas which are seen as promoting insecurity and violence globally and locally. These – violence, oppression, gender exclusion and gender-based violence, poverty, inequality, ecological destruction – need to be resisted and transformed. At the same time the figure can be used to identify positive areas leading to peace and global security for all: social and political participation and inclusion, just distribution of resources, ecological sustainability, nonviolent approaches to conflict and change. These need simultaneously to be encouraged and developed.

The scope is wide, because the problems themselves are far reaching and the goal inclusive. No one actor or organisation or field of activity can do it all. Far from it. But all of us can find ourselves somewhere in this frame and, from where we are, contribute in a tangible way to overall change. And all of us can, starting from an analysis like this, begin to see where our allies are and think about building coalitions and platforms across the different areas of work and struggle. We can, in summary, help build a shared vision between the many people and organisations striving for a better, more just world. It is a comprehensive, inclusive vision embracing peaceful relationships, economic justice, environmental protection, civil liberties and political participation.

Questions for reflection

• How do you respond to this figure?

• Where can you find yourself in it?

• What possibilities can you see for being more inclusive in your approach, while still keeping your area of focus?

• Can you see new possible allies?

• What conclusions can you draw from thinking in this way?

What, then, do we mean by conflict transformation? In a nutshell, we can say that it is a broad field of theory and practice, which addresses the social and political sources of conflict at all levels, and seeks to transform the negative energy of violence into positive social and political change.

It includes the field of conflict resolution, which aims to resolve specific conflicts, and tries to prevent them happening again, through building lasting relationships between hostile groups.

It aims to change structures that cause inequality and injustice, and to develop processes and systems which promote empowerment, justice, peace, development, environmental balance, healing and reconciliation. (See Chapter 4 for more on the essentials of conflict transformation.)

The crucial element in making change happen

The name, however, is not important, and conflict transformation makes no claim to encompass or control other areas of activity for a better world. We do want, however, to clarify what skills and expertise are on offer within this whole domain. We suggest that the insights and tools of conflict transformation practitioners and academics can contribute a great deal to the achievement of broad social and political change goals, such as human rights, development, environmental protection and transparent and participatory democracy. This community of practice has developed and tested many methodologies, frameworks and approaches to dealing with conflict, which are applicable to bringing about change within all these different areas. Change in any and all of these is likely to involve conflict – mainly between those who see themselves as winners and losers, included or excluded. To handle conflict skilfully is therefore key to achieving positive goals in human rights, development, the environment or any of the other fields of change.

However, relations between practitioners in these fields are not always harmonious. For example there is sometimes tension between human rights advocates and peacebuilders due to the different approaches adopted to conflict and disagreement. When peacebuil...