![]()

1 Trends in Sweet Cherry Production

This is an exciting time to be a sweet cherry producer. Today, growers have access to an unprecedented selection of high quality cultivars, precocious and dwarfing rootstocks, and high yielding innovative training systems. Additionally, increasing recognition of soil biology as an integral component of a healthy, productive orchard system is changing the way that orchards are managed. New technology that facilitates mechanization of some production, harvest and postharvest practices is being developed to respond to the uncertainty and increasing expense associated with the labor supply. Although new challenges, such as invasive pests and a changing climate, also are apparent, research and innovations are expected to continue to develop greater efficiencies, reduced inputs and higher quality fruit as growers adopt new orchard practices.

Sweet cherry research and development, along with market demand, have shown an upward trend since the late 20th century. In the 1990s, new rootstocks and training systems initiated the shift towards high density cherry production for the first time, resulting in earlier yields, greater returns on investment and orchard profitability. Smaller trees and innovative training systems facilitated the development of ‘pedestrian’ orchards. No longer was it necessary to harvest trees with ladders that were up to 6 m (20 ft) tall, but rather some orchards provided the potential to harvest all of the fruit from the ground, without ladders. At the same time, sweet cherry breeding programs in Canada, Germany, the USA, and elsewhere around the world significantly increased new cultivar fruit size while maintaining fruit firmness for long-distance export.

1.1 Global Production

Since the mid-1980s, cherry growers in Turkey, the USA, Chile and other countries have expanded production to supply greater fresh market exports to Europe and Asia. In fact, with only a few exceptions (mostly in Europe), sweet cherry production has been expanding around the world, increasing from 1.7 million t in 2000 to over 2.6 million t in 2015, a gain of about 54% (O’Rourke, 2016). Increases in production have been especially dramatic in China and Chile. According to the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), China increased production from 11,000 t in 2000– 2002 to 380,000 t in 2017, and Chile increased production from 29,333 t to 206,741 t in the same period. This moved China and Chile to the third and fifth largest producers in the world in 2017 (O’Rourke, 2018). Expansion was not limited solely to these two countries, however. Of the top five global producers in 2001 (Turkey, USA, Iran, Italy and Spain), Turkey and the USA have at least doubled their harvested area since the mid-1980s. All of this expansion is being driven by fresh market demand, as the market for processing cherries has remained essentially static or has even decreased over the same period, mirroring similar trends in other processed fruits.

Although past trends are no guarantee of future direction, all of the leading cherry producing countries have the potential to not only expand production area, but to increase yields through orchard renovation to higher density plantings using dwarfing rootstocks and new training systems that maximize both yield and fruit quality. Furthermore, it is not just the leading countries, but also previously minor countries such as Uzbekistan and Bulgaria, that are expanding production rapidly, using new technology to improve yields and fruit quality.

As sweet cherry production continues to expand worldwide, each producer must decide whether to increase production (either through the renovation of old orchards or expansion into new sites), continue at a steady pace or decrease acreage and thus reduce risk but also yields. Since growing cherries is a high risk venture, the best way to proceed will depend on past successes and failures, perceived risks, the possibilities for mitigating those risks and future market potential. With a few notable exceptions, the fresh market has so far been able to absorb increased production through expansion into new territory and increased buying power in developing markets. A good example of this is China, where imports from both the northern and southern hemisphere have increased exponentially, yet so has new domestic production capacity. As recently as 2000, few consumers beyond China’s eastern coast cities had ever seen cherries in their markets. As direct imports increased, mainly from the USA, Australia and Chile, and as the buying power of the Chinese middle-class consumer has grown, the Chinese market has absorbed an ever increasing amount of cherries. Future market stability will depend not only on a continued expansion of the Chinese market, but also in strengthening currently weak markets (such as India) and other developing economies. Since cherries are perceived and marketed as a luxury item, most sales are made to middle- and upper-class consumers, so continued growth in these markets is vital to the overall success of the worldwide cherry industry as well as to individual producers.

1.2 Fresh Market Sweet Cherry Production – yield, fruit quality and economics

Expanding acreage is not always the best strategy for every grower. Many producers believe that bigger operations are always better, but economies of scale with regards to equipment investment, labor availability and matching supply to demand are critical components of profitability. Producing more cherries during certain times of the season may actually depress prices, leading to a smaller per unit return, and requiring labor when availability is at its most competitive (and thus costly). US growers often farm relatively large cherry orchards of 40 to 80 ha (100 to 200 acres) or more. However, it is not uncommon for European producers to farm only 5 to 10 ha (12 to 25 acres) of cherries. The average price received by US growers for a unit of cherries often is less than that received by many European producers. In this case, finding a unique market niche, protecting the crop from inclement weather to increase yields per area, or increasing fruit size to take advantage of premium prices, may be a better strategy than expanding orchard size.

Similarly, ideas of expansion of production capacity must be weighed against potential impacts on fruit quality. Producing the largest, highest quality fruit possible may increase profitability in the long run for producers since larger fruit is often more efficient to pick, tends to ship better, arrives better, holds up longer on the market shelf and receives a higher price than smaller fruit of the same cultivar. Most packing houses can sell larger fruit for a premium. As production has increased, many packers have stopped marketing smaller cherries for fresh consumption. It is now rare to see fresh market packages that include 21 mm (12-row) cherries, and more common to see fruit that averages 28 mm or larger (9.5-row and larger). Some training systems, such as the super slender axe (SSA), produce a high proportion of fruit at the base of one-year-old shoots, which is typically larger, firmer and sweeter than fruit produced on spurs (on two-year-old and older branches). Most training systems, however, produce a greater proportion of the crop on spurs, resulting in higher yields per tree but smaller average fruit size. As will be discussed in detail in later chapters, whatever orchard production system is chosen, fruiting site renewal has become a critical part of orchard management, to maintain a balance of new shoots and young (relative to older) spurs, which helps maintain the production of higher quality fruit throughout the life of the orchard.

1.3 Organic Sweet Cherry Production

Growers not only have choices regarding rootstock, variety and canopy training, but also general orchard management, including codified management systems associated with a specific identity for the buyer or end user. Many ‘sustainable management’ programs delineate specific practices or tools that can or cannot be used. These typically relate to environmental impact, human health impact and treatment of workers. As more institutional buyers, such as supermarket chains, develop their own sustainable management programs, their suppliers (i.e. growers) are required to also show compliance with specific standards or principles. The resulting ‘product attributes’ may be communicated to the end consumer as labels signifying ‘pesticide free’, ‘GMO free’ or ‘organic’, or may simply be tracked internally as part of sustainability metrics or future liability protection. ‘Certified organic’ is one of the more widely used codified management systems for fruit crops, and the production area of sweet cherries managed organically has been increasing globally.

Organic production is legally regulated in many countries, and sales of food products labeled ‘organic’ are highly regulated in the two dominant markets, the European Union and the USA. Therefore, commercial growers considering organic production would need to undertake a formal organic certification process. Many resources (e.g. the USDA National Organic Program, www.ams.usda.gov/about-ams/programs-offices/national-organic-program, accessed 19 June 2020) are available online to help growers understand this process and determine whether it might be a good fit.

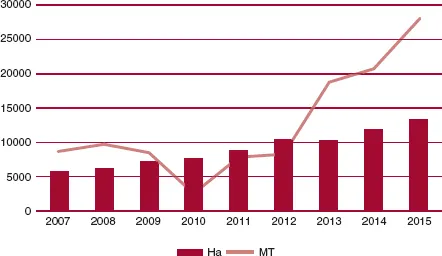

The global area of organic (certified and transition) sweet cherries was estimated in 2015 to be 13,282 ha (32,806 acres), which does not include China, a major country for organic tree fruit production (Willer and Lernoud, 2017). Figure 1.1 illustrates the changing production area (hectares) and estimated global production (tons) of organic sweet cherries over the past decade. When compared with data from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) for all cherries, organic production comprised ~3% of global area and 0.8% of global volume. Organic production area increased slightly from 2012 to 2015 while tonnage increased dramatically. Turkey and Italy had the greatest area of organic production in 2015, while the USA produced the most organic fruit (Table 1.1). A rough estimate of orchard yields (dividing production by area) suggests that organic cherry yields in the USA far surpassed other countries, although these values do not account for the amount of area in transition or new plantings that were not yet producing an organic crop.

Fig. 1.1. Global organic sweet cherry production area (hectares, ha) and volume (tons, t) (Kirby and Granatstein, 2017; Willer and Lernoud, 2017).

Table 1.1. Major producing countries for organic sweet cherries in 2015, with the top three ranked (in parentheses) by area, production, and estimated yield per orchard area (Kirby and Granatstein, 2017; Willer and Lernoud, 2017).

| Area (ha) | Production (MT) | Yield (MT/ha) |

Turkey | 3165 (1) | 6832 (2) | 2.16 |

Italy | 2776 (2) | 6035 (3) | 2.17 |

Bulgaria | 1618 (3) | 879 | 0.54 |

USA | 1082 | 8714 (1) | 8.05 (1) |

Poland | 1041 | 328 | 0.32 |

Spain | 449 | 1468 | 3.27 (2) |

Hungary | 491 | 1228 | 2.50 (3) |

Organic cherry prices in Washington State, the leading US producer, were 55–65%higher than conventional prices for 2014–2016, and the year to year patterns have been similar since 2008. Depending on production region, major challenges for organic producers include spotted wing Drosophila (SWD), black cherry aphid, plum curculio, cherry powdery mildew, brown rot, bacterial canker and cherry viruses. The recent advances in genetics, biocontrols and horticulture all apply to organic systems. Reliance on one primary organic control option for SWD (i.e. spinosad) is an ongoing concern and research focus.

1.4 Future Production Issues and Innovations

Sweet cherry production, from planting through growing, harvesting and packing, is extremely labor intensive. In fact, labor is the single most expensive input for most cherry growers around the world. Reducing labor costs can increase potential grower profits. However, the labor issue is not just a matter of more profitable production; labor in most production areas of the world is becoming more diffi...