![]()

SECTION I

THE

STORY

OF MILLING

![]()

CHAPTER 1

A Brief History

Like so many early features in history, our knowledge is based on the distilled comments and interpretations of many different chroniclers. This leads to a variety of opinion that can seem difficult to resolve and indeed this confusion is very true of our earliest machine – the waterwheel.

What seems generally agreed is that man used the flow of water in a river or stream to power simple mechanisms at least as long ago as 200 BC. There are three basic devices that are known from early Roman times: the horizontal waterwheel, often called a Norse wheel; the Noria; and the undershot vertical waterwheel. Some claim the Norse wheel comes from earlier centuries in Greece but others suggest that the evidence for this is very weak. Indeed, some suggest that it might well have come last of the three. What we do know is that all three machines were widely used and survived in various forms into the 19th century, with a few making it into the 20th century.

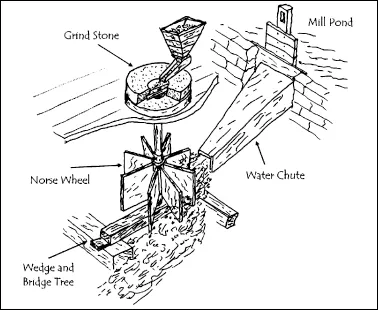

The horizontal wheel consisted of a vertical shaft around the bottom of which were fixed radial boards or paddles. The water flow was directed at these paddles so that it caused them, and the shaft, to rotate. The rotating shaft was used to directly turn a grindstone to make flour.

The very earliest versions adjusted the gap between the grinding stones (a feature, as we shall see, that was very important) by a system of wedges set into the shaft, but very soon this was replaced by the ‘tenter beam’ or ‘bridge tree’, as shown in Fig 1.1. This beam carries the bottom bearing of the vertical shaft including the paddles and the top ‘runner’ stone. By adjusting one end of this beam the top stone can be raised or lowered, thus altering the gap between the stones, a process known as tentering. These wheels were relatively simple to construct and could also turn a modest-sized grindstone using very little water flow. Its simplicity made this type of wheel common in small rural communities and some were still in use up to the last century in Scotland and Ireland.

FIG 1.1: Possible arrangement of an early horizontal wheel flour mill. The arrangement of the stones and the way the grain was fed had been established by the Romans and remains virtually unchanged to this day. This type of wheel became known popularly as a Norse wheel.

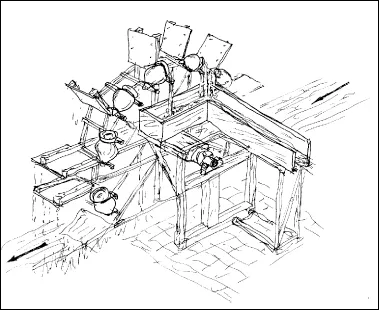

The vertical wheel is the type we think of as the traditional water wheel. The paddles are set on a much larger diameter than the Norse wheel and the shaft that holds them is horizontal, carried in two bearings. The Noria was a variation of the vertical wheel used to lift water and was a self-contained machine that did not drive anything else. It consisted of a wheel which carried around one side a series of pots or buckets. The bottom and the lowest pots were in the flow of a river, which turned the wheel.

The pots filled with water at the same time and were carried, rather like a big wheel at a fairground, up to the top where they would empty their contents into a trough, which carried the water away. Used for irrigation and water supplies to towns, they were built to surprisingly large diameter – certainly up to 50 ft (15 m) and possibly larger.

Roman engineers developed a variation on this theme, where they devised an undershot wheel to turn a separate ‘chain of pots’. This used water containers, sometimes earthenware pots, sometimes wooden boxes, which were strung together to form a continuous loop. The bottom of the loop dipped into the river and the top tipped the water-filled pots into a wooden channel, thus directing the water as required. They were normally driven at the top and thus required gears and shafts from the waterwheel, so not only could they be used to raise water from a river but the same ‘chain of pots’ could be driven at the top and used to lift water up from a shaft or mine.

FIG 1.2: This figure shows the principle of the Noria. The pots are held out from the wheel in order to pass over the receiving trough. There are quite a few drawings of what historians believe the Noria may have looked like but, alas, many are not mechanically feasible!

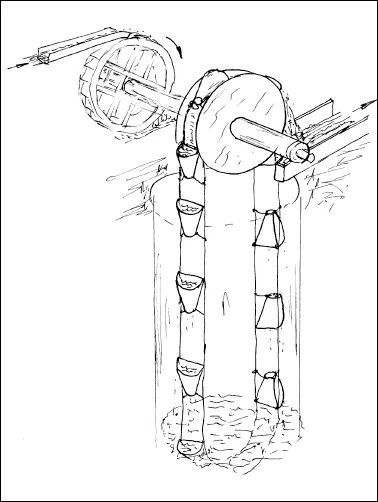

The main use of the traditional vertical wheel was always to turn grindstones to make flour, though the rotating horizontal shaft of these waterwheels could also power hammers and certainly it was used to crush stone from the very beginning. The horizontal shaft, however, is no use for grinding flour and here the breakthrough almost certainly came from the Romans – gears.

The first gears were used simply to take the power from the rotating horizontal shaft and turn it through 90° to drive a vertical rotating shaft. It didn’t take too long before the engineers realised that by making the gear wheels of different sizes, it was possible to alter the speed of the vertical shaft. The earliest mills seem to have been made with the gears giving a slight reduction in speed to the vertical shaft and we must assume that these needed a fast-flowing river or stream to create a fast-turning wheel. We must also remember that these early mills still used a version of the old hand-turned style of grindstone, shaped rather like an hourglass, called a quern. (See Fig 5.2) It took a while before the flat stones, that we think of today, were developed. We must also remember that at first these early waterwheels were relatively rare.

FIG 1.3: Chain of Pots. Our knowledge of these devices is fairly limited. They were most commonly driven by men or horses. Getting water for the wheel was usually a problem – mines and streams are rare companions! There must have also been a fair waste of water when the pots turned over as the trough catching the water has to have a gap to allow the pots to descend again.

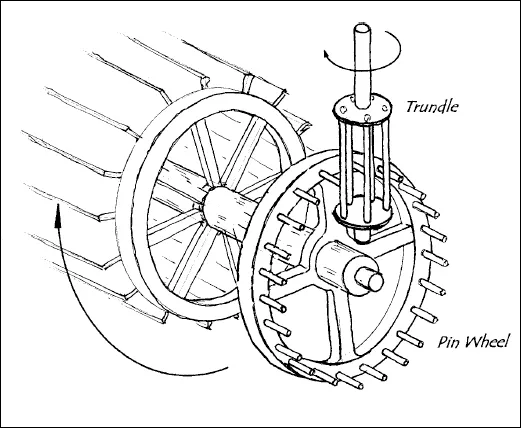

FIG 1.4: Early Roman gearing using pins (pin wheel) and a trundle (which was rather like a simple bird cage) where the pins mesh with vertical bars of the cage. Relics of this very old gear system can still be found.

Up to around AD 250 the Roman Empire still used its abundant supply of slaves and cheap labour as the normal power source. As the Empire began to ebb this labour source started to shrink and by AD 350–400 the Romans were putting serious effort into constructing waterwheels to replace their slaves. Roman writers also describe breastshot and overshot wheels though these seem to have been only rarely used at this stage. Indeed the breastshot wheel had to wait for a better understanding of waterwheels before it really blossomed. In Britain there is evidence of Roman use of waterwheels not just for grain but for driving hammers to crush ore.

We must remind ourselves that all this was going on some 2,000 years ago! Whilst the Romans used iron for small items, the majority of these structures would have been made entirely from wood, as indeed they would be for the next 1,500 years.

The Romans eventually left our shores around AD 400 and the next 700 years became known as the Dark Ages. Originally ‘Dark’ because there seemed to be so little evidence of what life was like during this period, slowly, research is filling in more detail. However, despite several invasions and many regional battles, life went on. The monasteries tended to make what we might call the scientific advances – they dominated ironmaking and improved agriculture – but everywhere the humble waterwheel continued to grind flour and crush stone and ore. All large monasteries and estates would have had their own waterwheel-driven mills and indeed the notorious system, where tied tenants were forced to use t...