- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

English Canals Explained

About this book

The English canal network becomes increasingly popular and widely used each year. The aim of this book is to explain how everything works—from locks and lifts, to tunnels and towpaths. Stan Yorke, a life-long narrowboat enthusiast, explains in an easy-to-understand manner the story of the canals. In this he is ably assisted by his son Trevor's super drawings and diagrams. The book is divided into three clear sections. The first describes the history of the canals, the second looks at their structures and features, and the third suggests special sites of interest around the country, which can be visited on foot or by boat.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

SECTION II

THE

CANAL SYSTEM

TODAY

CHAPTER 3

The Waterway

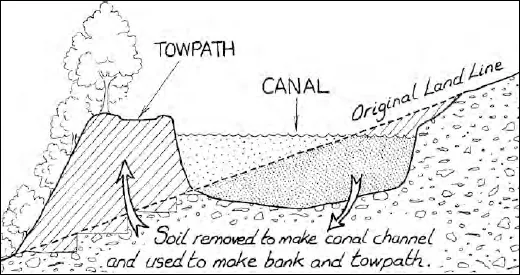

The canal itself is simply a waterproof ditch, the dimensions of which were influenced by the size of craft that were to use it – not very romantic until you add the water and boats! The trench that was to become the canal was dug, or formed in the case of embankments. It would then be lined with a clay or loam ‘puddle’ mixture which would make it waterproof. This lining varied across the country dependent on local materials and could be several feet thick if the underlying soil was very porous. There is a lovely story of how Brindley was called to Parliament to explain just why the water in a canal wouldn’t soak away. He took suitable clay and water with him to Westminster and worked the clay to form a bowl into which he duly poured the water. It didn’t leak, thus demonstrating to the dubious onlookers that it had become waterproof. These days, apart from where dredging has been done to remove years of silt from the bottom of the channel, you will rarely see anything of this lining. Very occasionally you may notice the top of a modern concrete lining employed to cure a difficult, leaky section such as on the Llangollen or the Kennet & Avon canals. This modern edging often hides a much more ambitious solution. Sometimes, if fear of slippage is the problem (usually when the canal is on the side of a hill), steel shuttering will have been driven in 15 or 20 ft deep. Where leakage is the problem a butyl liner is placed across the entire canal, rather like a pond at home, then a full concrete lining is poured giving a somewhat unattractive canal but one that doesn’t lose water.

FIG 3.1: Section through a typical contour canal showing how the ground was used to prevent having to carry soil to or from the site. The canal channel would then be lined with a waterproof layer of puddle.

FIG 3.2: Ill-defined but beautiful offside banking typical of many miles of canal where there is no risk of a breach or slippage.

Very occasionally the route of a canal was changed, sometimes to replace problem structures, sometimes to accommodate railway or road construction and very rarely to actually shorten the route. Brindley originally built three sets of staircase locks on the Trent & Mersey canal but these soon became a cause of delays and were all rebuilt as conventional individual lock flights. The original routes can still be seen at Meaford locks north of Stone and at the Lawton locks above Kidsgrove. Similarly the remains of the original route of the northern Oxford canal can still be found wandering away from today’s long straight sections.

Towpaths

There is one rather obvious feature that makes canals particularly attractive to us today and that is the towing path. Rarely provided on rivers due to land ownership problems, they were fundamental to canals where the movement of boats, up to the late 1800s, was always by means of towing. It’s these paths, now extensively refurbished, that enable us to enjoy and explore the system today, but please remember they are part of the canal and in most cases are technically not public rights of way. The towpaths were normally constructed on the side of the canal where the land was lowest. That side needs a strong bank to prevent slippage and leakage and the towpath bank thus serves two purposes. The canal companies also owned the land on the non towpath side. In order to build the canal they had to purchase a strip of land wide enough for the canal, the towpath and the offside bank. During the decades of neglect the companies failed to mark or maintain these borders. Today we have housing and farmland running down to the water’s edge but nevertheless British Waterways own the first metre or so of the land – a source of endless quarrels!

FIG 3.3: Modern steel piling being driven in along a washed out section of bank. The wooden structure acts as a guide whilst the piles are driven down into the canal bed and then the gap behind is infilled with silt and mud dug up from the canal bed (dredging).

FIG 3.4: Modern piling being topped with stonework to give a more attractive finish. The canal here is following a river valley and suffered from slippage. The towpath edge has been strengthened by driving in 15 ft steel piling to prevent further movement.

FIG 3.5: Old triangle shaped winding hole and wharf at Brewood, north of Wolverhampton. The wharf is now in use as a hire boat base and boatyard.

Bank Protection

Wear and tear on the canal sides was anticipated from the start and sometimes a ledge would be deliberately created in which reeds would be planted. This provided a catchment area for soil being washed off the towpath and the plants helped to absorb the impact of the wash from the boats. Many modern boaters complain of these shallow edges, believing them to be due to lack of maintenance, but they have been used from the very beginning.

In the 20th century, due to the greater turbulence of powered craft, the towpath edges have needed reinforcing, firstly with wooden piles, then concrete piles and more recently with galvanised steel. These are tied back to smaller piles driven into the towpath several feet back from the water’s edge. Sometimes if the towpath has been neglected the top of these tie back piles will show in the middle of the towpath or the tie rods will be exposed.

FIG 3.6: This simple overflow weir is unusual as it provides a cobblestone walkway for the horses and a raised path for people, though this pathway was built much later.

New piling is usually carried out when the original edging has collapsed and the canal is ill defined. The piles are driven in where the original edge would have been or often slightly further out in order to avoid any stonework still in place below the water line. The resultant area between the new piling and the eroded towpath is then filled with dredgings from the canal, very messy! Later it is seeded and left to dry out. If when walking a towpath you find an unusual amount of bricks and bits of branches in the surface you can be sure that you are walking on dried out dredgings.

The older brick, stone and wooden edging, often well worn, allowed grasses and weeds to grow and hang over into the water, helping the beautiful integrated feel of rural canals. The modern piling is far less helpful to plant life and the galvanised steel piling will probably never be covered over, at least not until it is so rusted that it no longer does its job.

Turning Around

As most working boats were longer than the canal was wide, winding holes, that is a deliberate widening of the canal, were provided for craft to turn around or ‘wind’ in (this word is usually pronounced with a soft ‘i’ as in window). They were usually placed near wharfs where boats would load or unload and then need to return in the direction they came from. If you find one today with no commercial buildings nearby it may give a clue to the existence of a long gone wharf. In many places the wharf would be built along one side of a triangular winding hole, thus combining both needs in one place.

FIG 3.7: This draining sluice has its own railings surr...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Section I: A Brief History

- Section II: The Canal System Today

- Section III: What To See

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Waterway Organisations

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access English Canals Explained by Stan Yorke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.