eBook - ePub

Heroes of Bomber Command Yorkshire

Michael Wadsworth

This is a test

Share book

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Heroes of Bomber Command Yorkshire

Michael Wadsworth

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In this excellently researched book Michael Wadsworth describes the air war in Yorkshire, and the young men who flew night after night against desperate odds.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Heroes of Bomber Command Yorkshire an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Heroes of Bomber Command Yorkshire by Michael Wadsworth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World War II. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

From Leaflets

to Bombs

‘Whatever people will tell him [the man in the street] the bomber will always get through. The only defence is offence…’

Stanley Baldwin: the House of Commons,

10 November 1932

10 November 1932

Many airmen who were to achieve real distinction in subsequent years started their early operations in a Yorkshire setting. Driffield airfield alone, in the early months of the war, had a concentration of talent and distinction: Leonard Cheshire, VC, began his ops with 102 Squadron at Driffield, for instance, as did Melvin Young, who was to take part in the ‘bouncing bomb’ Dambusters Raid, while Hamish Mahaddie, a sergeant pilot on Driffield’s other squadron, 77, would become CO of the Pathfinder Navigation Training Unit down at Warboys in Cambridgeshire. Two Yorkshire pilots – Cyril Barton and Andrew Mynarski – were to be awarded the Victoria Cross, posthumously, for their heroism in the air.

During the Second World War the Yorkshire Wolds (and later on, the moors and dales) would become home to 25 airfields, several to be used in training or by fighter aircraft, but the majority of them as airfields of Bomber Command. On the outbreak of war in September 1939, however, solid, brick-built aerodromes housed six operational squadrons, all equipped with the redoubtable Armstrong-Whitworth Whitley bomber. The new airfields (built in the previous three to five years) were Driffield, at the foot of the Yorkshire Wolds and home of 77 Squadron and 102 Squadron; Dishforth, adjacent to the Great North Road and east of Ripon, home of 10 Squadron and 78 Squadron; Linton-on-Ouse, north of York, housing 51 Squadron and 58 Squadron; and Leconfield, near Beverley, which was retained briefly on a Care and Maintenance basis before reverting to Fighter Command.

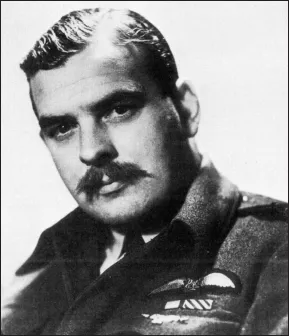

F/S Hamish Mahaddie and his crew when he was a pilot on 77 Squadron at Driffield. (Hamish Mahaddie)

All these squadrons were members of 4 Group, Bomber Command. In 1936 the RAF had created a functional Command system to replace the old area organization of the Air Defence of Great Britain. Thus 4 Group in the Yorkshire Wolds was founded in 1937. Its HQ was then, rather improbably, at Mildenhall in Suffolk, but was soon relocated to Linton-on-Ouse and then to Heslington Hall in April 1940, just outside York. The first Group Commander was Air Commodore (as he was then) Arthur Harris, but by 1940 the post was held by Air Vice Marshal Cunningham. Air Marshal Sir Edgar Ludlow-Hewitt was succeeded as Commander in Chief of Bomber Command in 1940 by Sir Richard Peirse, who held office until early 1942 and was replaced by the legendary Sir Arthur Harris, whose name became synonymous with Bomber Command.

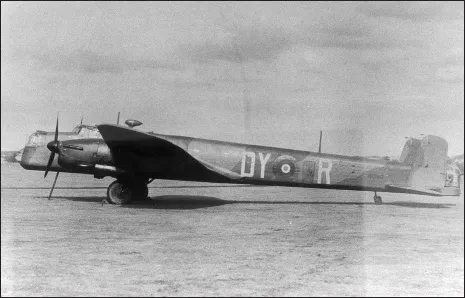

77 Squadron Whitley Vs at Driffield. (Peter Green)

Staff officers at 4 Group HQ, Heslington Hall, York. Sir Roderick Carr, AOC 4 Group, fourth from left. (51 Squadron archive)

The Whitleys of 4 Group were to take the war to the enemy and their long range, though not their inadequate bomb-carrying capacity, was initially considered sufficient for this. Disastrous encounters with German fighter aircraft in daylight, while attempting to attack enemy shipping in the North Sea, soon made night bombing a prudent necessity. It is no exaggeration to say that the Yorkshire-based squadrons were at the raw edge of developing night-bombing techniques.

Pre-war, the men who flew the Whitleys had been attracted into the RAF by the offer of cadetships at Cranwell, or by the prospect of a short service commission. The creation of the RAF Voluntary Reserve aided this process, as did the University Air Squadrons, which brought Melvin Young and Leonard Cheshire to Driffield. From the very outset of the war the RAF was almost a Commonwealth air force, men from the Dominions coming to this country in quest of a short service commission.

Crews getting ready to board a Whitley for a raid. (Peter Green)

Developing a trade at the RAF Apprentices College at Halton also gave an opportunity to learn to fly. Hamish Mahaddie learned to fly in this way. Men in the pre-war RAF enjoyed the increase in pay which serving as an air gunner or wireless operator in a bomber gave them. The great thing was to fly, and there were many ‘air minded’ enthusiasts amongst the youth of those days. The problem was that, with the advent of war, training had to be speeded up and navigational proficiency, to highlight one vital requirement, could only be developed by long and arduous practice. Furthermore, navigation required proficiency in mathematics and, at the very least, a good standard of education. Pilots and navigators had to be a special breed. With the coming of Stirlings and Halifaxes and the need for a flight engineer, ex-Halton entrants were encouraged to volunteer, as were men with technical engineering apprenticeships behind them.

A bomber crew needed an entire arsenal of skills and training. Aircrew were rapidly becoming the most highly trained men in the history of armed warfare. There was never any shortage of volunteers for aircrew even though, as was the case in early 1943, only about 17% of RAF bomber crews could expect to finish a 30-operation tour.

The first night operation took place only hours after war had been declared on 3 September 1939, when ten Whitleys from 51 and 58 Squadrons at Linton-on-Ouse flew to Leconfield to load up with leaflets for what was known as a ‘Nickel’ raid, dropping propaganda over Germany. Five nights later on 8 September, S/L Philip Murray of 102 Squadron set out from Driffield on a leaflet-dropping raid and had to bale out over enemy territory when his aircraft suffered engine failure. He and his crew became the first POWs and were taken by their captors to meet Hermann Goering himself, bloated and gloating over them.

Linton-on-Ouse – home of 58 Squadron – from the air. (Peter Green)

On 11 October a report came in to Bomber Command HQ from Air Vice Marshal Cunningham, who wrote: ‘The real constant battle is with the weather. The constant struggle at night is to get light onto the target.’ The Group Commander predicted ‘a never ending struggle to circumvent the law that we cannot see in the dark’.

A Whitley V at Leeming – note the heavy camouflage. (Peter Green)

A Whitley V of 102 Squadron, Driffield, having returned from bombing Sylt; pilot S/L Macdonald. (Peter Green)

The excellent thing from a Group Commander’s point of view, however, was the negligible opposition from the Luftwaffe. The real enemy at this stage, as Cunningham had noted, was the weather, in particular the severe icing encountered and the impossibility of maintaining height. Not only would ailerons, rudders and elevators become frozen and jammed, but even inside the cockpit instruments would freeze. Fragile oxygen systems became unusable. And meanwhile St Elmo’s Fire or a lightning storm might spell annihilation for an unwary or unprepared crew.

Two of the earliest Distinguished Flying Crosses (DFCs) of the war were awarded to pilots of 102 Squadron, both New Zealanders. F/O Gray and F/O Long brought a severely damaged Whitley back to Driffield on the night of 27/28 November 1939, after it had been nearly torn apart by lightning over the target. F/O Frank ‘Lofty’ Long, DFC, went on to become Leonard Cheshire’s mentor when Cheshire flew second pilot to him during the middle of the next year. Twenty-five-year-old Long was killed on the night of 12/13 March 1941 on a Berlin operation. Over the little village of Denekamp in Holland, his Whitley was attacked by a Messerschmitt and exploded in mid-air. The local people never forgot the incident, and in 2002 a memorial to the crew was unveiled in the Dutch village.

The distances covered on leaflet raids were sometimes vast, as, for example, the Nickel raid on 26 January 1940 when crews had to fly to Villeneuve in France as a forward base against Prague, Vienna and Munich. Conservation of fuel and accuracy of navigation were therefore a problem. On the night of 15/16 March 1940, a Whitley of 77 Squadron was forced to land due to bad weather on what they thought was mainland France, only to find, from the attitude of the locals, that they were on the wrong side of the Franco-German border. Running back to their aircraft and to a quick take-off to avoid the ‘hue and cry’, they made it to the forward French airfield of Villeneuve with almost no fuel in their tanks.

And still, in this ‘phoney war’ period, the first actual bombing raid had yet to take place. It came at last in March, after the Germans had bombed the base of the home fleet in Scapa Flow, on the north coast of Scotland. Bombs were scattered over the Isle of Hoy, killing one civilian and wounding seven in the village. So now the gloves were off. On the night of 19/20 March, 30 Whitleys from 4 Group and 20 Hampdens raided the German seaplane base at Hornum on the southern tip of the island of Sylt. Twenty-six Whitleys claimed to have found the target and to have bombed accurately.

Whitley V (102 Squadron) Driffield. (Peter Green)

The press made much of the contribution of the two Dishforth squadrons, 10 and 51, and stated that the raid had been led by the CO of 10 Squadron, W/C ‘Crack Em’ Staton. This annoyed the Driffield crews, as a Flight Commander from 102 Squadron, S/L J.C. Macdonald was the first over the target and had in fact bombed first. A party from 102 Squadron entered Dishforth in the early hours of the morning of 22 March and left leaflets under the plates in the Officers’ Mess stressing Driffield’s premier contribution. The Dishforth crews in reply carried out their own leaflet raid on Driffield. Perhaps, for all the irony, that was a good way for the ‘phoney war’ to end, although officially and historically it ended when Germany invaded Norway on 8/9 April 1940.

Now offensive raids with real bombs were conducted by the Whitleys of 4 Group against Norwegian airfields and also against oil refineries in the Ruhr. On 14 May the Luftwaffe’s indiscriminate terror policy was underlined by a raid on Rotterdam after the German invasion of the Low Countries. The next night Bomber Command sent 108 aircraft to attack more targets deep inside Germany – the start, so some scholars maintain, of the strategic bombing offensive.

Casualties inevitably began to make themselves felt as operations hotted up. Of six aircraft from 102 Squadron at Driffield attacking a synthetic-oil plant at Gelsenkirchen-Buer on the night of 19 May, two (piloted by F/O Longman and F/S Hall) failed to return, while others had narrow escapes. The next night, during a raid by 38 Whitleys of 10 Squadron from Dishforth, two more were shot down, while another two Whitleys were destroyed by enemy ground fire when attacking bridgeheads and enemy troops the night after, with the crew of one, captained by P/O Geoff Womersley of 102 Squadron, baling out near Metz.

W/C (later G/C) Geoff Womersley, CO of 139 Squadron (PFF) and Station Commander of Gransden Lodge (PFF). Started off as a young P/O of 102 Squadron at Driffield. (Geoff Womersley)

Geoff Womersley was thus spared for an astonishing wartime career, ending up as Station Commander of the Pathfinder Force RAF station at Gransden Lodge in Bedfordshire. He flew operationally Whitleys, Wellingtons, Lancasters and Mosquitos, and ha...