![]()

1

Bomber Command

The Lie of the Land in 1942

Formed in July 1936, Bomber Command’s early existence relied heavily on a popular slogan of the day; ‘the bomber will always get through’. This thinking relied heavily on the fact, (which in part was true at the time) that the average bomber of the mid-1930s had virtually the same performance as the average fighter and as such would receive very little opposition when approaching an enemy target. It was believed that anti-aircraft defences would cause some casualties and that only some of the fighters that had been scrambled in time would harass the bomber on its return journey but, generally, this method of attack was seen as a way of causing total destruction and therefore was the perfect deterrent to future wars.

However, the mid-1930s was a period of rapid military development while the world accelerated into an unavoidable Second World War. Aircraft were part of this technological race which saw both the capacity and the range of bombers increase significantly while fighters gained more horsepower, more effective weapons and improved their general all-round performance to a point where very few bombers could escape on their capability alone.

In July 1936, the RAF was equipped with a range of biplane bombers such as the Hawker Hind, Boulton Paul Overstrand, Fairey Gordon and Hendon, Handley Page Heyford and the Vickers Virginia, the latter having served in various marks since the early 1920s. The eleven Auxiliary squadrons serving with Bomber Command also fielded a collection which included the Hawker Hart and Hind and the Westland Wallace and Wapiti. To think that machines of this calibre would be thrust into a worldwide conflict in just over three years’ time must have sent some serious warning signals to the Air Ministry and, as a result, the development of a new breed of bombers had already begun.

Hawker Hind light bombers of 15 Squadron in 1936 capable of delivering a total bomb load of 510lb. Less than five years later, the squadron was operating the Short Stirling with the capacity to carry 14,000lb of bombs.

By the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, the Bomber Command inventory had dramatically changed. The biplane had yielded to the multi-engined monoplane with one exception; the Fairey Battle. The Battle was not the greatest of aircraft and its failings were exposed during the Fall of France in 1940 when losses quickly saw this light bomber despatched to the second line. The remainder, which made up Bomber Command’s Order of the Battle in September 1940, were the Bristol Blenheim, Vickers Wellington, Armstrong Whitworth Whitley and Handley Page Hampden. All of these machines were destined to take part in the ‘Thousand Bomber’ raids, although it was only the reliable and rugged Wellington which would remain in frontline RAF service for the entire war. The Wellington would also be the most prolific type to join the ‘Thousand Bomber’ raids and it was not until 1943, when production of the four-engined heavies began to gain momentum, that this Barnes Wallis, geodetic-designed classic began to yield.

As well as the aircraft already mentioned, prior to May 1942, four more bombers had joined the Bomber Command inventory. The first, the Short Stirling, entered Bomber Command service in August 1940 followed by another heavy, the Handley Page Halifax, in November. The twin-engined Avro Manchester and first bomber variant of the de Havilland Mosquito followed in 1941 while the four-engined Avro Lancaster entered service in early 1942. Further resources, such as the Douglas Boston and Havoc were also available, thanks to ‘Lend-Lease’ from early 1941. This, on paper, gave Bomber Command a formidable capability which, when harnessed under the right leadership and despatched in an organised fashion, could strike a serious blow against the enemy.

The Blenheim was the fastest bomber in the RAF inventory at the beginning of the Second World War but by 1942 was already obsolete. However, it would play a key role in the ‘Thousand Plan’. These are 57 Squadron machines; by May 1942 the unit had converted to the Vickers Wellington. Bristol Aircraft

However, while this collection of aircraft appears impressive, Bomber Command still only had one type available in numbers which could deliver a large bomb load even though it was classed as a medium bomber; namely the Wellington. The Blenheim, by 1942, was serving with 2 Group in the light bomber/intruder role, while the Whitley and Hampden, both medium bombers and mainly serving with 4 and 5 Groups respectively lacked the clout, although both were good, respected aircraft in their own right. With regard to the new heavy bombers, the Stirling and Halifax were still not available in large numbers; the Manchester proved to be virtually ineffective thanks to mechanical issues and the Lancaster, fresh into service, was still finding its feet, although the latter was already hitting the headlines.

The Rolls-Royce Vulture-powered Avro Manchester, which thankfully led to the highly successful Lancaster. 99 sorties were flown by this unpopular aircraft during the three ‘Thousand Plan’ raids.

By May 1942, there were five marks of Wellington in operational service; the Bristol Pegasus or Rolls-Royce Merlin-powered Mk IA, which by then was serving with the OTUs (Operational Training Unit); the Mk IC, again serving with OTUs but still on the front line with several squadrons of 1 and 3 Groups; the Merlin-powered Mk II, serving in small numbers with 1 and 4 Groups; the Bristol Hercules-powered Mk III, again in small numbers with two 3 Group squadrons and the Pratt & Whitney Twin Wasp-powered Mk IV, operated by three Polish and two Australian squadrons within 1 Group.

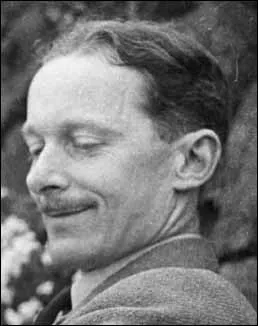

T.R.1335, aka GEE

As well as the appointment of a more aggressive AOC and the potential for more modern and capable aircraft at its disposal, Bomber Command was also about to benefit from the introduction of a new navigation aid. Known by the spring of 1942 as GEE (aka T.R.1335), this radio navigation system was the brainchild of Dr Robert ‘Bob’ Dippy, a young scientist who joined the TRE (Telecommunications Research Establishment) in 1936, initially working on radar development at the newly-established RAF Bawdsey Manor, located in plain sight on the Suffolk coast. While the main thrust of Bawdsey was radar development under the charge of James Watt descendent, Robert Alexander Watson-Watt, scientists like Dippy were also looking at other electronic aids such as a potential blind landing system which expanded the experiments at the time that would lead to the highly successful Chain Home Radar network. Dippy’s proposed blind landing system would be made up of a pair of transmitting antennas located ten miles apart and positioned on each side of the runway. A master transmitter located directly between them sent a signal to both antennas which made sure that the same signal was broadcast from the outer antennas at exactly the same time. The receiving aircraft would receive the signals which were then displayed via an A-scope which was an early form of radar display which measured distance from the radar to the target using a horizontal axis. If the aircraft was approaching the centreline of the runway, both signals would be received instantaneously but if the aircraft was off the centreline, one signal would be received before the other and a pair of ‘peaks’ would appear on the A-scope. Depending on which signal was received first would place the aircraft either closing on the runway or flying away from it.

The backbone of Bomber Command, the Vickers Wellington, up to the arrival of the four-engined heavies, was the only aircraft capable of delivering a good sized payload against the enemy. Air Ministry

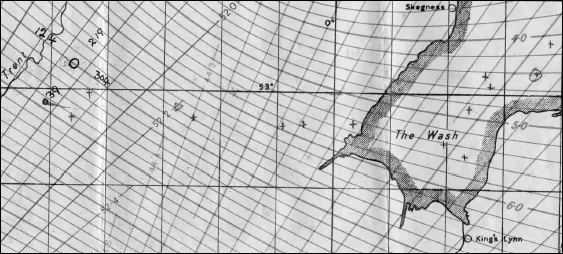

A small sample of an original GEE Chart used by the navigator of a Lancaster. Via Alastair Goodrum

Supported by Watson-Watt, Dippy put forward his proposal for this new navigational aid to the Air Ministry and subsequently to Bomber Command as early as 1938 but his idea was met with apathy. Bomber Command’s response at the time was a little arrogant and somewhat short-sighted. As far as they were concerned, the high standard of training that RAF navigators received at the time, which in part was true, was more than up to the level required, certainly in peacetime. Even as another inevitable world war was on the horizon, there was no thought given to an offensive war and the use of radar was purely aimed at defending rather than attacking which, as we know, would help to save Britain during a certain battle in 1940.

Dippy would continue to improve his navigation aid in 1940, when development was transferred to the TRE outpost at St Aldhelm’s Head, south of the village of Worth Matravers, just under five miles west of Swanage on the Dorset coast. In response to early losses suffered by Bomber Command, Dippy was asked to continue his research in an effort to expand his original blind landing system into a long-range position fixing system which could put a bomber much closer to the target than had been achieved to date. On June 24, 1940, Dippy presented his new idea which revolved around a grid system and, as such, it was initially coded ‘G’ which was expanded to ‘GEE’ in July 1940 but would still only be referred to as T.R.1335 behind closed doors.

The system was relatively simple; the bomber picked up three signals emitted from a trio of well-spaced ground transmitters. The central transmitter was the master station while the outer two were known as the slaves, these being ‘triggered’ by pulses from the master. The pulses were then displayed on a cathode ray tube positioned above the navigator’s table, complete with an internal measuring device. The difference in time between the signals from the master and each of its slave stations were translated on a special grid which had lines of constant difference. Once this information was collected, the navigator would use his GEE chart, which was covered in hyperbolic lines, to plot the aircraft’s position.

Initial testing was promising and the system was showing signs of being accurate up to 300 miles away (as far as the Ruhr from an East Anglian airfield) if the bomber was flying at 10,000ft. Further tests were carried out on October 19, 1940 which just utilised a pair of GEE transmitter systems and even this was accurate up to 110 miles at an altitude of 5,000ft. It was clear that the system had legs and, by the end of 1940, a number of sites across Britain had been requisitioned for GEE ground stations which became officially known as the AMES Type 7000, 30-60 MHz Hyperbolic Navigation System.

Service trials of GEE did not begin until May 15, 1941, the delay partly being due to security, a lack of bombers equipped with it and, more crucially, major problems with making one of the valves needed for the system, the latter not being fully resolved until August. It was that same month when GEE was trialled operationally for the first time when a pair of 115 Squadron Wellingtons were equipped with the device. These two aircraft, along with 27 other Wellingtons, were ordered to attack Mönchengladbach on August 11/12, 1941 and, conveniently, as if to test the GEE system to its maximum, the target was completely cloud-covered. Much improved accuracy was achieved but, during a raid to Hanover the following night, one of the GEE-equipped Wellingtons, Z8835 ‘KO-U’ was lost, potentially delivering sensitive equipment on a plate to the enemy. History has told us that this did not happen but the RAF was not prepared to use GEE any further until a minimum of 300 bombers could be equipped with the aid. Only days after this final operational trial was carried out, Bomber Command was given the all clear to use GEE but mass production would not begin until May 1942. In the meantime though, 300 ‘hand-made’ GEE sets would be ready for operational use by January 1, 1942 and these would play their part in the ‘Thousand Plan’.

A Type Receiver, T.R.1335 GEE unit on the left and the navigator’s cathode ray tube display unit on the right. Via Alastair Goodrum

Dr. Robert ‘Bob’ Dippy, whose general navigation system was developed into the GEE. Purbeck Radar Museum Trust

GEE was not used operationally again until March 8/9, 1942 when 211 bombers attacked Essen with the Krupps Works being the focal point. Unfortunately, a problem which had saved this target from destruction many times before, namely industrial haze, played its part yet again and both the city and works escaped virtually unscathed which was not an encouraging start for the new navigation aid in which the RAF had placed so much faith. Other raids would follow and the first successful GEE-led operation took place on the night of March 13/14 when 135 bombers struck Cologne. This raid also saw flares and incendiary bomb...