- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In recent months, much attention has been paid to Islam and the greater Muslim world. Some analysis has been openly hostile, while even more has been overly simplistic. Islam in Context goes behind the recent crisis to discuss the history of Islam, describe its basic structure and beliefs, explore the current division between Muslim moderates and extremists, and suggest a way forward.

Authors Peter G. Riddell and Peter Cotterell draw from sources such as the Qur'an, early Christian chronicles of the Crusades, and contemporary Muslim and non-Muslim writings. They move beyond the stereotypes of Muhammad-both idealized and negative-and argue against the myth that relatively recent events in the Middle East are the only cause for the clash between Islam and the West.

Riddell and Cotterell ask the non-Muslim world to attempt to understand Islam from the perspective of Muslims and to acknowledge past mistakes. At the same time, they challenge the Muslim world by suggesting that Islam stands today at a vital crossroads and only Muslims can forge the way forward.

Islam in Context will appeal to all those who are interested in an alternative to the easily packaged descriptions of the relationship between Islam and the West.

Authors Peter G. Riddell and Peter Cotterell draw from sources such as the Qur'an, early Christian chronicles of the Crusades, and contemporary Muslim and non-Muslim writings. They move beyond the stereotypes of Muhammad-both idealized and negative-and argue against the myth that relatively recent events in the Middle East are the only cause for the clash between Islam and the West.

Riddell and Cotterell ask the non-Muslim world to attempt to understand Islam from the perspective of Muslims and to acknowledge past mistakes. At the same time, they challenge the Muslim world by suggesting that Islam stands today at a vital crossroads and only Muslims can forge the way forward.

Islam in Context will appeal to all those who are interested in an alternative to the easily packaged descriptions of the relationship between Islam and the West.

Information

1

BEGINNINGS

When Muhammad was born in Mecca, more than five centuries after the birth of Christ, a movement was initiated that would utterly transform Arabia and the fortunes of the Arab peoples in the space of a mere twenty years. Few men have had a greater impact on world affairs, lasting century after century, than this man Muhammad.

Muhammad ibn Abdullah was born in Mecca, probably in the year 570. By the time of his death at the age of sixty-two he had brought into existence a dynamic movement that would carry Islam through the centuries and across the continents, birthing empires, transforming the sciences, and challenging economic, cultural, and political systems. At the twenty-first century, as occurred frequently in its past history, the Islamic faith that sprang out of Muhammad finds itself at a crossroads, facing a choice between a radical identity willing to use violence to achieve its goals, and a moderation that could accept and even welcome coexistence with other cultures; a choice between moving ahead along a single highway or pursuing separate roads, with travelers on each nervously eyeing the others.

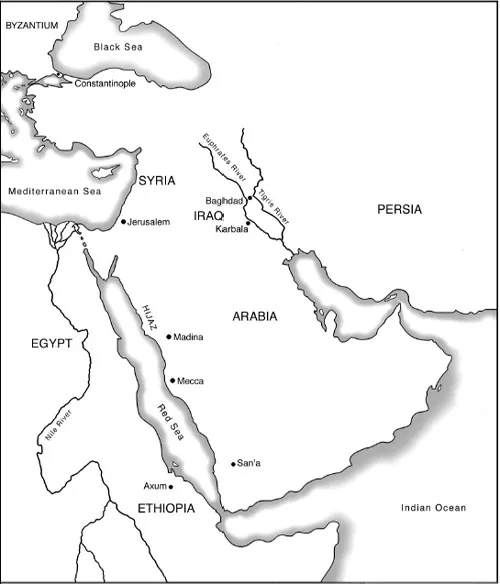

ARABIA BEFORE MUHAMMAD

Muhammad came to a no-people. The Arabs were largely ignored by the two great empires of the sixth century: the Christian empire centered on Byzantium (Constantinople, the modern Istanbul), over to the west; and the Zoroastrian Sassanian empire to the east, in Persia. It is, perhaps, not surprising that Arabia was ignored. The great Empty Quarter held no attraction for the traveler, and the sea route to India had made the old overland caravan trail obsolete. The Arabs were peoples, not a people. The main thing that united them was their language, and even that was fragmented into a score of dialects.

The peoples of the Arabian peninsula had for centuries been largely nomadic, moving from one oasis to another, from one patch of scant pasture to another, as water or vegetation failed.[1] Mecca had long been a center for trade, but through the years more and more people moved from the arid desert wastes to this new and fascinating city, with its Zamzam well, reputed to have healing properties.[2] But urbanization, as always, brought with it problems. Out in the desert the rules were clear: look after your own clan. An attack on one is an attack on all. The need of one is the need of all. Fighting is unavoidable and noble. Death in fighting for the clan is an honorable death. If you are fortunate enough to live into old age, the clan will care for you, provide for you. Orphans, too, will be cared for. Every member of the clan of a few hundred people knew everyone else.

FIGURE 1.1. THE NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST

In the city all this was changed. Now there were the anonymous poor, with no one to care for them. There were fortunes to be made and lost, and with the fortunes went power. Beggars roamed the streets, orphans looked for help, the aged needed care. As always, the rich got richer but were never rich enough.

They had no religion in common. What they had was a confusing mixture: the worship of sun and moon, and stars, probably borrowed in part from the Zoroastrians, the worship of strangely shaped or unusually large stones, the worship of the spirits of trees and wells and springs. And providing it all with some kind of unity was the worship of idols, several hundred of them. The focal point for that unity was Mecca, where stood the Ka‘ba, that cube-shaped storehouse for more than three hundred idols, kept by the Quraysh tribe and presided over by an official guardian.[3]

The term Ka‘ba is related to the English word cube, and the building was just that, a cube-shaped building. It was not the only cube-shaped storehouse for idols in Arabia, but it was the most important. From time to time it had been destroyed by some accident and had to be rebuilt. At the time of Muhammad’s birth, the Meccan Ka‘ba was distinguished by a large stone built into one wall, the Black Stone. Later tradition maintained that the stone was originally white and had been given to Adam, some said to Abraham, as the foundation stone for the first House of Worship. But that was later tradition: at the time it was simply part of the stone worship of Arabia. Here, unexpectedly, is one of the important and perhaps surprising links of modern Islam to those early days, for the Ka‘ba in Mecca in the twenty-first century contains that same Black Stone. It is certainly surprising that in such a strongly monotheistic religion as Islam a stone should play such a central role.

South of Mecca lay the great city of San‘a, home to a good many Christians. Across the Red Sea lay the Christian kingdom of Ethiopia, founded on the lives of two Syrian Christian young men, Edesius and Frumentius, who had been shipwrecked on the Red Sea coast sometime in the fourth century. It was probably Ethiopian influence that was responsible for that Christian presence in San‘a. In the years ahead, the histories of Islam and Ethiopia would impact on each other many times.

MUHAMMAD: A PROPHET DISDAINED

When Muhammad was born in 570, his father, Abdullah, was already dead. This meant that his mother, Amina, was robbed of a husband in a strongly patriarchal society. The name Abdullah, Abdu-llah, Servant of Allah, is a reminder that his son did not invent the name of the One High God whom millions of Muslims through the coming centuries would worship.

For any account of the life of Muhammad we have three obvious sources: the Qur’an, the Traditions (Hadith), and the earliest biography of Muhammad that has survived, the Sira by Ibn Ishaq, translated into English by Alfred Guillaume and published as The Life of Muhammad.[4]

A Life of Muhammad?

The following attempt at a brief biography of Muhammad generally follows Ibn Ishaq and the Qur’an, but a quite different biography can be put together by playing down these obvious sources.[5] And that is possible, first, because there is no universal agreement among scholars as to the date when the Qur’an came to be written and assembled, and second, because Ibn Ishaq was writing more than one hundred years after Muhammad’s death.[6] Not unconnected is, third, the fact that in the period after Muhammad’s death traditions concerning his life and teaching began to accumulate, to multiply, some mere pious fabrications, some fabrications to support some disputed point of Muslim practice, some genuine memories. There is a good Muslim tradition saying that when Bukhari, one of six Muslim scholars who edited authoritative collections of these Traditions, came to assemble what he considered to be a reliable collection of them, he selected fewer than three thousand different Traditions from a total of six hundred thousand,[7] one half of 1 percent. And yet it must have been from these oral and written traditions that Ibn Ishaq compiled his Sira.

The position is summed up conservatively by Patricia Crone and Michael Cook:

There is no hard evidence for the existence of the Koran in any form before the last decade of the seventh century, and the tradition which places this rather opaque revelation in its historical context is not attested before the middle of the eighth. The historicity of the Islamic tradition is thus to some degree problematic: while there are no cogent internal grounds for rejecting it, there are equally no cogent external grounds for accepting it.[8]

These two scholars proceed to set aside the traditional sources. Of the resulting biography Clinton Bennett says:

According to these writers, Muhammad’s life, as recorded in the Sira, is largely the invention of later generations; the real Muhammad was a Messianic-type figure who led a movement to re-possess Jerusalem; the Qur’an was posthumously composed sometime during the Khalifate of Abd al-Malik.[9]

The biography set out here takes a more positive view both of the Qur’an and of Ibn Ishaq’s Sira, but at the same time recognizes that what we have in both is a redaction, a rewriting of events from the perspective of a period after Muhammad’s death.

As usual in those days, the babe was put out to a wet nurse, a poor woman who would care for children until they were weaned, which might not be until they were three or even four years old. But this fact confirms other hints that the family was not a poor one. Indeed, it was an influential family. Muhammad’s grandfather, Abd al-Muttalib, was guardian of the Ka‘ba. His uncle, Abu Talib, was clan chief of the Hashimites, one of the ten or so clans that made up the Quraysh, the dominant tribe of Mecca.

The Year of the Elephant

Muslim tradition calls the year of Muhammad’s birth The Year of the Elephant as a reminder of the attempt of the Ethiopian Regent in southern Arabia, the Yemen, to destroy the Ka‘ba. In 523 there was a massacre of Christians in Yemen, and the Byzantine emperor, Justin, called on Ethiopia to go to the aid of the Christians there. This example of Christian solidarity in the face of non-Christian threats was to be repeated during the Crusades over five hundred years later.

Not only did the Ethiopians defeat the oppressors, they also annexed the Yemen to Ethiopia, whose emperor sent a man named Aryat as his viceroy. Aryat was soon displaced by the ambitious Abraha, defeated in single combat and killed. It was probably Abraha who built the big church in San‘a. This church quickly established itself as a pilgrimage destination and was on track to eclipse the Ka‘ba in Mecca. Rivalry between the Yemenis in the south and the Meccans to the north became more and more bitter, exploding when one of Abraha’s allies in the Hijaz area between the two was assassinated. Abraha mounted a punitive expedition with the express intention of destroying the Ka‘ba.

According to legend Abraha assembled an army of some twenty thousand men, and added to them thirteen elephants, headed by an enormous beast named Mahmud. The advance guard entered Mecca and took a certain amount of plunder, including two hundred camels belonging to Muhammad’s grandfather, Abd al-Muttalib, guardian of the Ka‘ba. He went out to meet Abraha and demanded the return of his camels. Abraha received him with respect but said: “You pleased me much when I saw you; then I was much displeased with you when I heard what you said. Do you wish to talk to me about two hundred camels . . . and say nothing about your religion and the religion of your forefathers, which I have come to destroy?” To that Abd al-Muttalib replied: “I am the owner of the camels, and the temple has an owner who will defend it.”

The next day Abraha’s army advanced on Mecca, led by Mahmud, the elephant. But once Mecca was in sight, the elephant refused to advance. Still facing Mecca it knelt down, and no amount of beating with iron bars or even with metal hooks could drive Mahmud to its feet. And now a strange cloud appeared in the west: great flocks of birds. As they came closer, it could be seen that each bird carried three stones, one in each claw and one in its beak. Some traditions said that the names of Abraha’s soldiers were written on the stones. As the birds swooped over the soldiers, they dropped their stones on the named targets, killing any man hit by his stone.

Now came a further wonder: a roaring sound heralded a sudden flood of water, sweeping down from the mountains. It raged through Abraha’s camp, sweeping away the bodies of Abraha’s soldiers. The scattered remnant of the army fled southward, among them Abraha himself, stricken by some dreadful disease. When he reached San‘a he died. There was only one survivor, Abu Yaksum, who took the melancholy story back to the Negus, the king, in Ethiopia,

and going directly to the king told him the tragic story; and upon that Prince’s asking him what sort of birds they were that had occasioned such a destruction the man pointed to one of them, which had followed him all the way, and was at this time hovering directly over his head, when immediately the bird let fall the stone, and struck him dead at the king’s feet.[10]

That is the legend lying behind the history that scholars are trying to establish. The reference to the stones may allude to an outbreak of smallpox, which first appeared in Arabia about this time. The flood of water may well refer to a dam that burst its retaining wall at this time. In any case, the story cannot refer to the year of Muhammad’s birth, 570; by then Abraha was already dead. The one reference to this event in the Qur’an is in Sura 105, but there is no suggestion there that the event coincided with the birth of Muhammad. According to J...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Introduction

- PART 1: LOOKING BACK

- PART 2: IN BETWEEN: THE EBB AND FLOW OF EMPIRE

- PART 3: LOOKING AROUND

- Conclusions

- Select Bibliography

- Index

- Notes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Islam in Context by Peter G. Riddell,Peter Cotterell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Middle Eastern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.