- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A guide to essential aspects of Old Testament exegesis.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Interpreting the Old Testament by Broyles, Craig C., Craig C. Broyles in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Biblical Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Interpreting the Old Testament

Principles and Steps

The Nature of the Old Testament: Divine and Human

Divine Origins and Inspiration: Reading the Bible as Scripture

Before we study methods of interpreting the Bible, we must first consider briefly what the Bible is and how it works. The means we use to interpret an object depend on its nature and function. The most distinctive feature of the Bible is its claim to divine inspiration. Unlike other literature, its author is God. Much has been debated about the precise meaning of the claim that “all Scripture is God-breathed” (2 Tim. 3:16 NIV) and how the claim works out in the Bible itself, but even more important than our cognitive apprehension of this concept is our attitude. Exegesis of the Bible should be an adventure, filled with anticipation and holy fear, because in exegesis we hear the voice of the living God.

Our pursuit of the precise meaning and implications of the Bible’s inspiration, we will discover, goes hand in hand with the exegetical process. If the exact meaning of “God-breathed” or “inspired” is simply a presupposition of our exegesis or derived from a theological system, our understanding of inspiration comes not from within but from without—in other words, the Bible becomes what we think it should mean. For example, if we respect the variety of forms in which God has packaged revelation, we recognize that a simplistic, prophetic model of inspiration (i.e., that “thus says the Lord” entails God’s dictation to an individual prophet) does not work for the whole Old Testament.[1] Second Timothy 3:16 is clear on the Bible’s ultimate cause, but it says nothing about the immediate causes or means that God used in the formation of Scripture.

Human Agency: Reading the Bible as Literature and History

Although divine in origin, the Bible is not a book “dropped from heaven,” without human mediation. Nor is it a handbook of theological principles that are immediately accessible and applicable to all cultures at all times. It uses literary forms and imagery that are not immediately plain to modern readers (e.g., why does Yahweh call to the heavens and the earth when bringing an accusation against the people in Ps. 50:1–7 and Isa. 1:2–3?). Its many obscure references—from Abaddon to Zion—illustrate that the Bible is wrapped in history. The Bible makes the profound claim that God acts in history, but this entails a need for history lessons. Even the most uninitiated reader of the Bible soon becomes aware that God’s means of revelation are human, including language, literature, history, and culture.

Much of biblical literature refers to historical people, places, and events. God has not packaged revelation in mere literature, whether through fictional stories or theological propositions (a systematic theology). God has revealed himself through both word (literature) and event (history). Revelation comes through the medium of historical events and a historical people and their culture. The benefits of this dual medium is that God grants us not mere ideas or mystical experiences but a historical basis for our faith. We can be sure that God can intervene in our own historical experience because we have historical precedents. The flip side of this form of revelation is that it is historically contingent. It is occasioned or elicited by particular historical circumstances (the Bible is occasional literature). To be sure, many circumstances arise at God’s initiative (the historic saving events of God), but many arise from Israel’s doing (e.g., the history of Israel’s kings) because Israel, or another ancient Near Eastern people, did something on its own. In other words, certain issues appear in the Bible by “historical accident.” While the Bible has a universal message, it comes in a form that is contingent on circumstances and concepts of ancient times. We cannot limit “inspiration” to the original speech or the act of putting stylus to scroll; God supervises a process that includes authors and their personal experiences, audiences and their circumstances, historical events, cultural and social traditions, literary conventions (e.g., genres and figures of speech), and transmission history (including a book’s adoption into canon).

The Nature of Interpretation: Interpreters and Processes

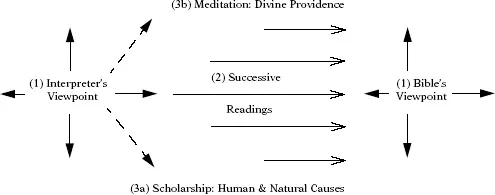

Table 1

The Interpreter’s Viewpoint and Self-Examination

Table 1 illustrates some of the issues and processes involved in interpretation. To use Hans-Georg Gadamer’s metaphor, the goal of interpretation is the “fusion of horizons” between text and interpreter (see the items numbered “1” in table 1). As Anthony Thiselton says, “The goal of biblical hermeneutics is to bring about an active and meaningful engagement between the interpreter and text, in such a way that the interpreter’s own horizon is re-shaped and enlarged.”[2] Interpretation begins with the interpreter and the Bible, along with their respective “horizons” (depicted by the north-south-east-west grid), at some distance from each other.

The first subject for the interpretation of the Bible is thus not the Bible, but the interpreter. Before we consider the object of our study, we must consider our perspective or viewpoint. As phenomenology has made clear, whenever we observe phenomena, we never see the bare phenomena alone, objectively, in and of themselves. We see them through the eyeglasses of our language, culture, and personal experiences.

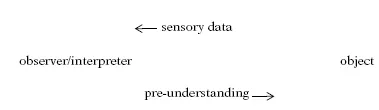

Without being aware of it, we are not mere recipients of sensory data. To try to understand, we simultaneously attempt to integrate what we see with what we have learned. The arrows go in both directions: while the phenomena stimulate our senses, we likewise project on them our prior assumptions and experiences. We must therefore attempt to “bracket” our pre-understanding in order to come to terms with the phenomena in their own right. The telling question each must ask is, What are my vested interests and how might they bias and prejudice my reading of the Bible? What assumptions, presuppositions, and tendencies do I bring to the text? As humans, we must acknowledge our tendency to avoid the light the Bible casts upon us, especially its diagnosis of sin in the human condition.[3] We all bear cultural assumptions. In North America, for example, we tend to focus on techniques and technology when faced with problems, rather than on character. We all bear theological or denominational assumptions that act as eyeglasses. Passages that are an integral part of our theology are brought into focus, while the rest remains a blur. We all carry personal assumptions, which are the hardest to discern. We may, for example, hold a belief tenaciously, not because we are exegetically and logically convinced, but simply because a trusted and beloved Bible teacher told us so. Self-examination is essential if we want to correct our inevitable astigmatism. A faith-affirming approach to Scripture means choosing to listen to it as God’s medium of revelation, but it does not mean that we presume to know what its contents claim or what our theological conclusions should be.[4]

Successive Readings

As we begin our interpretation of the Bible and its viewpoint, we proceed through successive readings and approximations of its meaning, each time—theoretically at least—moving closer to fusing our horizons with those of the text (see item 2 in table 1). Through these successive readings and through trial and error, we alternate repeatedly through the processes of analysis and synthesis, and of deduction and induction. In the process of analysis we study the Bible by breaking it down into its constituent parts, thus uncovering its detail and depth. Through synthesis we study how those parts form a whole that is greater than their sum. If we engaged in mere synthesis, however, our interpretation would be too simplistic and flat.

In theory, our model of exegesis is primarily inductive, in which we go from the particulars of the text to inferring general principles. In practice, however, we must inevitably engage in deduction, in which we go from general principles, derived from our culture and theology, to their expression in the particulars of the text. The mere fact that the Bible comes in human words means we must have some pre-understanding of these codes. As soon as we read, “In the beginning God . . . ,” we must project onto “God” our theological assumptions.

Scholarship. As noted in brief consideration of the nature of the Bible, it is “God-breathed” and thus divine, but it is also mediated through human agency. To appreciate the mystery of this “incarnation” of divine revelation we must, as part of our analysis, take deliberate steps to view it as both thoroughly divine and thoroughly human (see item 3 in table 1). Reading the Bible as Scripture means we submit to its authority; reading the Bible as literature and as history means we engage it “critically”—not with a faultfinding attitude, but with the exacting tools of scholarship. To understand what God says, we must study what God’s human agents have said, according to the linguistic and literary conventions of their time. We must first acknowledge our “distance” from the Bible—to us today its language is foreign, its history remote, and its cultural assumptions sometimes strange. We need to employ the tools of the university—linguistics, literary criticism, history, archaeology, geography, anthropology, sociology, psychology, and philosophy—as they apply to biblical studies.[5]

If we, in fact, regard the Bible as “God-breathed,” we should not shrink from asking any question or applying any exegetical tool, whether “critical” or not. Scripture, by virtue of its author, will prove itself when put to any legitimate test. If we assert the full divinity and humanity of Scripture, we must search both dimensions fully. An advantage of searching the human dimension is that it brings the Bible “closer to home.” We see biblical writers and characters living amid life’s complexities just as we do. Otherwise, if we imagine them as “saints,” always in touch with God and never affected by the social conventions and pressures of their day, then we divest ourselves of models with whom we can identify.

Meditation and Faith. The exercise of scholarship is helpful so long as we also embrace the divine realities of Scripture and the world it describes. (The same holds, of course, for our interpretation of our own personal experiences, which are also affected by both divine and human, or natural, interventions.) The Bible’s ultimate purpose follows from its unique claim. Because it is God-breathed, it is also God-revealing. Our primary goal in interpretation should follow from the Bible’s reason for being.

This realization poses a problem of how biblical exegesis is often taught in seminaries, universities, and Bible colleges. Whether one espouses the historical-critical method (often simplistically assigned to “liberals”), the historical-grammatical method (often simplistically assigned to “conservatives”), or the literary method (often simplistically assigned to “post-modernists”), the starting point is the text and factors such as genre, literary devices, traditions, and historical and social backgrounds. Thus, whether consciously or subconsciously, we begin with the human factors of the text. This is understandable, because the Bible is packaged as human communication, from authors and editors to various audiences. These are the features susceptible to the tools and skills of scholarly exegesis. But the effect of this starting point and the ensuing process is that we explain so much of the shaping of the text by human causes and influences that they may overshadow the spiritual and the divine. We then tend to relegate to God merely the aspects of the text that defy human probabilities. The theological deposit resulting from our exegesis is reduced to a “God of the gaps.” In fact, the more “successful” we are at this form of exegesis, the more we explain the shaping of the Bible from historical, sociological, and literary factors, and the less we feel the need to invoke God.

Irrespective of the immediate agents of and influences upon the Bible’s formation, its ultimate author and redactor is God. Before, during, and after our scholarly analysis of our passage, we must deliberately engage in prayerful meditation, whereby we access the text’s primary author and speaker through the illumination of the Holy Spirit. We must recognize and acknowledge through deliberate, personal encounter that the transcendent God speaks to us. God who “dwells in unapproachable light, whom no one has ever seen or can see” (1 Tim. 6:16), to whom nothing can be compared (Isa. 40:18, 25)—no “likeness,” image/symbol, metaphor, sign, or language—this God nonetheless “breathes” forth Scripture (2 Tim. 3:16) in words that liken him to human images, so we may gain a glimpse of him. Our exegesis of the Bible must always be imbued with this tension—otherwise we contradict its express nature and purpose. We should neither wish to devalue the Bible (a “liberal” tendency), nor to reduce the real God to the God “contained” in the Bible (a “conservative” tendency; cf. 1 Kings 8:27).

The leading question for the believing exegete should be, What is at stake in this passage? What difference does it make? By beginning with such questions, the interpreter focuses on the key existential issue. Our primary purpose and drive for reading the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- 1. Interpreting the Old Testament: Principles and Steps

- 2. Language and Text of the Old Testament

- 3. Reading the Old Testament as Literature

- 4. Old Testament History and Sociology

- 5. Traditions, Intertextuality, and Canon

- 6. The History of Religion, Biblical Theology, and Exegesis

- 7. Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- 8. Compositional History: Source, Form, and Redaction Criticism

- 9. Theology and the Old Testament

- Scripture Index

- Subject Index

- Notes