eBook - ePub

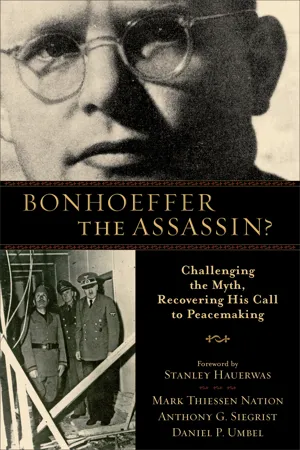

Bonhoeffer the Assassin?

Challenging the Myth, Recovering His Call to Peacemaking

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Bonhoeffer the Assassin?

Challenging the Myth, Recovering His Call to Peacemaking

About this book

Most of us think we know the moving story of Dietrich Bonhoeffer's life--a pacifist pastor turns anti-Hitler conspirator due to horrors encountered during World War II--but does the evidence really support this prevailing view? This pioneering work carefully examines the biographical and textual evidence and finds no support for the theory that Bonhoeffer abandoned his ethic of discipleship and was involved in plots to assassinate Hitler. In fact, Bonhoeffer consistently affirmed a strong stance of peacemaking from 1932 to the end of his life, and his commitment to peace was integrated with his theology as a whole. The book includes a foreword by Stanley Hauerwas.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Bonhoeffer the Assassin? by Mark Thiessen Nation,Anthony G. Siegrist,Daniel P. Umbel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Theology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Bonhoeffer’s Biography Reconsidered

This book wrestles with theological ethics and the central question of the applicability of Jesus’s teaching in a sinful, violent world, but the main argument is inescapably biographical. We are exploring how one human being, a twentieth-century German theologian and church leader named Dietrich Bonhoeffer, reflected on these issues in the context of the Third Reich, one of the most oppressive and destructive regimes in human history. The first section, the next three chapters, provides a sketch of the whole of Bonhoeffer’s short life. Like any such account, this one will emphasize some elements and events more than others. Every effort has been made, however, not only to be fair in this portrayal but also to avoid distortion by omission.

1

“Pacifist and Enemy of the State”

On March 7, 1936, when Bonhoeffer was thirty years old and Hitler had been in power for a little more than three years, Bishop Theodor Heckel, director of the Church Foreign Office for the German Evangelical Church, expressed concern about Bonhoeffer’s influence.29 He wrote to church authorities that Bonhoeffer could “be accused of being a pacifist and enemy of the state” and that the Prussian church committee should “disassociate itself from him” and not allow him to provide theological training.30 Heckel’s twin accusations provide one way of framing this biographical narrative, for they point to two dimensions of Bonhoeffer that, if true, make him virtually unique among pastors and theologians in Germany in the 1930s and ’40s. Here was a man who, by 1936, had come to embrace what he himself referred to as pacifism, and yet already was being perceived by authorities as a threat to the state. By most accounts, it should be noted, the two accusations—pacifist and enemy of the state—are mutually exclusive. So who was this man who came to be identified in this way?

On February 4, 1906, Bonhoeffer was born into a tight-knit, upper-middle-class family, the sixth of eight children. Both parents were from influential, well-established families. Indeed, his father became one of the most respected psychiatrists in Germany.

Bonhoeffer’s family was patriotic but not militaristic. When World War I broke out, in 1914, and one of Bonhoeffer’s sisters “dashed into the house shouting ‘Hurrah, there’s a war,’ her face was slapped.”31 The Bonhoeffers did not celebrate war. On the other hand, a conflict undertaken by one’s own nation normally required assent and doing one’s patriotic duty. Thus it appears that the family did not hesitate to send all three of Dietrich’s older brothers to serve in the First World War, a conflict of unprecedented violence and loss. Speaking in November of 1930, in New York City, Bonhoeffer recalled that during World War I “death stood at the door of almost every house and called for entrance.” Germany, he said, “was made a house of mourning.”32

The Bonhoeffer home was not spared. Three of Dietrich’s first cousins died at the front. His brother Walter, born in 1899, was killed on the battlefield in April of 1918. According to Bethge, Walter’s death “seemed to break his mother’s spirit.”33 The loss of Walter “and his mother’s desperate grief left an indelible mark on Bonhoeffer.” Three years later, at Dietrich’s confirmation, his mother “gave him the Bible that Walter had received at his confirmation in 1914. Bonhoeffer used it throughout his life for his personal meditations and in worship.”34

When the Nazis came to power, Bonhoeffer’s immediate family saw the regime very early on for what it was. In fact, by the end of the Third Reich, two brothers and two brothers-in-law had been executed for being involved in the resistance movement.35 Nonetheless, we should not imagine that the household in which Dietrich grew up questioned the German patriotism of the day. As a child, Bonhoeffer responded enthusiastically to the early German successes in World War I.36 Indeed, through the late 1920s he seemed to be a fairly typical young German male. For instance, while a theological student at Tübingen, he took it in stride that he would join the Hedgehogs, the same patriotic fraternity his father had joined when he was a student. In November of 1923, as a member of this fraternity, Dietrich did two weeks of military training with the Ulm Rifles Troop, learning to use various weapons. He wrote to his parents, with apparent pride: “Today I am a soldier.”37

Just over five years later, in February 1929, as an assistant pastor of a German-speaking congregation in Barcelona, Spain, Bonhoeffer lectured on Christian ethics. In this lecture he spoke against applying the Sermon on the Mount to the present, because to do so was to violate the spirit of Christ and freedom from the law.38 He went on, in this lecture, to provide a rationale for killing enemies to protect one’s family and one’s fellow Germans. He said:

I will take up arms with the terrible knowledge of doing something horrible, and yet knowing I can do no other. I will defend my brother, my mother, my people, and yet I know that I can do so only by spilling blood; but love for my people will sanctify murder, will sanctify war.39

Eberhard Bethge notes that “neither in his sermons nor in his letters did [Bonhoeffer] ever make any such statements again.” Referring to such statements as “excessively nationalist,” Bethge goes on to say that such words “never crossed his lips again, for he now saw them transformed into nationalistic slogans and interwoven with anti-Semitic agitation.”40 It is important to be informed that Bonhoeffer never speaks like this again. However, is it possible that Bethge’s interpretive comments could be misleading? First, relative to typical German theologians in the late 1920s, Bonhoeffer’s statements, though couched in his own peculiar theology, would not have been perceived to be “excessively nationalist.” They would have been common ethical fare.41 Second, Bethge seems to be suggesting that Bonhoeffer dropped such language primarily because it could be co-opted by others, transforming his language “into nationalistic slogans and interwoven with anti-Semitic agitation.” Thus it is implied that clear shifts, obvious by 1932, are because of such practical, contextual concerns. However, the evidence suggests that in 1929 Bonhoeffer was on a serious theological (and spiritual) journey, a journey upon which he will be transformed during the 1930–31 school year, when he is in New York City. It is a journey that will come to mature expression theologically between 1935 and 1938. And the shifts in convictions that happen within this journey are shifts made through theological deliberation, in the context of transforming spiritual experiences, not because of the pragmatic concerns Bethge named.

Bonhoeffer departed Barcelona on February 17, 1929, upon completion of his one-year pastoral assistantship there. His return signaled his reentry into the academic world. He had done doctoral work in theology at the University of Tübingen and the University of Berlin between the summer of 1923 and the end of 1927. He defended his doctoral thesis, Sanctorum Communio, in December. In the summer of 1929, Bonhoeffer became an academic assistant in systematic theology for Wilhelm Lütgert, at the University of Berlin. During that term and the 1929–30 winter term, Bonhoeffer wrote his second (Habilitation) dissertation, Act and Being, in order to be qualified to teach in German universities. His thesis was accepted on July 12, 1930; he successfully completed his oral Habilitation examination that summer and thus was qualified to become a formal lecturer in the universities. On July 31 Bonhoeffer gave his inaugural lecture at the University of Berlin, “The Anthropological Question in Contemporary Philosophy and Theology.”42 In September of 1930, three years after it was originally written, a revised version of his doctoral thesis, Sanctorum Communio, was published.

Becoming a theologian was a goal Bonhoeffer had had since he was fifteen years old. Yet his father had reservations. Many years later his father expressed the concerns that he had felt at the time. Ironically, he feared that Dietrich would live “‘a quiet, uneventful minister’s life,’ which ‘would really almost be a pity’” for someone with his son’s obvious abilities.43 However, given the combination of Bonhoeffer’s own theological trajectory and the political events that would unfold within Germany over the next fifteen years, “uneventful” is far from describing his life.

During the process of qualifying to be a university professor, Bonhoeffer had applied for and secured a one-year fellowship to study at Union Theological Seminary in New York City. Bonhoeffer anticipated this time with eagerness. However, he could not have imagined the transformation he would undergo because of his year in the United States.

“A Grand Liberation”

As it happens, we know from Bonhoeffer himself about a transformation that occurred in his life sometime prior to 1933. He wrote about it in a letter to his girlfriend, Elizabeth Zinn, on January 27, 1936. It is so vital to our understanding of Bonhoeffer that we must quote it at length:

I threw myself into the work in a very unchristian and rather arrogant manner. A mind-boggling ambition, which many have noticed about me, made my life difficult and separated me from the love and trust of my fellow human beings. At that time I was terribly alone and left to my own devices. That was really a terrible time. Then something different happened, something that has changed my life, turned it around to this very day. I came to the Bible for the first time. It is terribly difficult for me to say that. I had already preached several times, had seen a lot of the church, had given speeches about it and written about it—but I still had not become a Christian, I was very much an untamed child, my own master. I know, at that time I had turned this whole business about Jesus Christ into an advantage for myself, a kind of crazy vanity. I pray God, it will never be so again. I had also never prayed, or at least not much and not really. With all my loneliness, I was still quite pleased with myself. It was from this that the Bible—especially the Sermon on the Mount—freed me. Since then everything is different. I am clearly aware of it myself; and even those around me have noticed it. That was a grand liberation. There it became clear to me that the life of a servant of Jesus Christ must belong to the church, and gradually it became clearer how far this has to go. Then came the troubles of 1933. They only strengthened me in this. At this time I also found people who looked with me toward the same goal. I now saw that everything depended on the renewal of the church and of the ministry. . . . Christian pacifism [christliche Pazifismus], which I had previously fought against with passion, all at once seemed perfectly obvious [Selbstverständlichkeit]. And so it went further, step by step. I saw and thought of nothing else. . . . My calling is quite clear to me. What God will make of it I do not know. . . . I must follow the path. Perhaps it will not be such a long one. Sometimes we wish it were so (Philippians 1:23). But it is a fine thing to have realized my calling. . . . I believe the nobility of this calling will become plain to us only in the times and events to come. If only we can hold out!44

Given some of the language Bonhoeffer uses, he appears to have in mind some specific experiences within a specifiable period of time that brought about this “grand liberation.” In fact, partly because of his reference to coming to see Christian pacifism as “perfectly obvious,” we can set chronological parameters for the transforming experiences he underwent. In February of 1929, when the lecture in Barcelona was given, we know that Bonhoeffer was still against pacifism. By the summer of 1932 he is giving lectures that passionately communicate his opposition to war, in theological terms, and sometimes specifically affirming pacifism. Between the Barcelona lecture and his 1932 lectures was Bonhoeffer’s time at Union Theological Seminary in 1930–31.45 So, it is not difficult to see his experiences in the United States as crucial to his transformation.

Yet it is also true that Bonhoeffer was already on a journey that led him to connect with experiences in New York City. Bonhoeffer, for instance, already had some experiences that led him to empathize with those who suffer. In a lecture in New York City on November 9, 1930, he noted: “I have been accustomed once in every year since my boyhood to wander on foot through our country and so I happen to know many classes of German people very well. Many evenings I have sat with the families of peasants around the big stove talking about past and future, about the next generation and their chances.”46 Dietrich informs family members of the varied people he interacts with regularly in his role as assistant pastor in Barcelona (1928–29), including those who are poor and those who are criminals.47 Specifically, on August 7, 1928, he writes to his friend Helmut Rossler:

I’m getting to know new people each day, at least their life stories. Sometimes one can also peer through their portrayals to the person—and in the process one thing is always striking; one encounters people here the way they are, far from the masquerade of the “Christian world”; people with passions, criminal types, small people with small goals, small drives, and who thaw a bit when you speak to them in a friendly manner—real people. I can only say I have the impression that precisely these people stand more under grace than under wrath, but that it is precisely the Christian world that stands more under wrath than under grace. “I am sought out by those who did not ask; . . . to those who did not call on my name I said, ‘Here I am’ (Isa. 65:1).”48

Bonhoeffer had prepared for such encounters, had hoped for them. Thus, in his doctoral thesis, Sanctorum Communio, finished in July 1927, Bonhoeffer critiques the church, saying, “Our present church is ‘bourgeois.’ The best proof remains . . . that the proletariat has turned its back on the church, while the bourgeois (civil servant, sk...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Endorsements

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Part 1: Bonhoeffer’s Biography Reconsidered

- Part 2: The Development of Bonhoeffer’s Theological Ethics

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Back Cover