- 624 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This beautifully designed, full-color textbook offers a comprehensive introduction to the world's religions, including history, beliefs, worship practices, and contemporary expressions. Charles Farhadian, a seasoned teacher and recognized expert on world religions, provides an empathetic account that both affirms Christian uniqueness and encourages openness to various religious traditions. His nuanced, ecumenical perspective enables readers to appreciate both Christianity and the world's religions in new ways. The book highlights similarities, dissimilarities, and challenging issues for Christians and includes significant selections from sacred texts to enhance learning. Pedagogical features include sidebars, charts, key terms, an extensive glossary, over two hundred illustrations, and about a dozen maps. This book is supplemented with helpful web materials for both students and professors through Baker Academic's Textbook eSources. Resources include self quizzes, discussion questions, additional further readings, a sample syllabus, and a test bank.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Introducing World Religions by Charles E. Farhadian in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Théologie et religion & Religion comparée. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

one

The Persistence of Religion

The Inescapable Context of Religion

We all live in contexts. We are contextual beings. No matter where we live, what we believe, or how we practice our faith, our contexts profoundly impact our formation as people. Yet it is far too easy to overlook the importance of our contexts. Contexts are universal, consisting of many shared elements. Our families serve as one of the most important and earliest contexts of our lives. We cannot understand religions without making sense of their broader psychological, social, cultural, historical, environmental, and religious contexts. Religions have always been deeply influenced by their contexts, but just how have they been shaped by their local conditions? The kinds of human problems addressed by a religion are problems that emerge in part out of local contexts, and the human needs reflected in any given location are a mixture of universal needs and those unique to a particular people and region. Even the natural environment, climate, and weather patterns can impact religion and religious life. The bottom line is that there are many people around the world who live with gods in their midst.

Figure 1.1. We all live in contexts

Stephan Babuljak

David Haberlah

Charles E. Farhadian

Figure 1.2. Families (Sudan, Papua, United States)

Charles E. Farhadian

Defining Religion

This is a book about religion, but what is religion? In this book, I follow what has been called a phenomenological approach to understanding religion. Given the vast diversity of religious traditions in the world, it is nearly impossible to establish a concise and precise definition of religion broad enough to capture all phenomena in all religions, without inaccurately representing some aspect of a particular religious tradition. However, Winston King, who wrote the definition of religion for the Encyclopedia of Religion, offers eight characteristics of religion that are useful general categories, even if they do not provide a succinct definition of religion itself (see sidebar 1.1).

Figure 1.3. A Hindu-Balinese God keeps watch

Stephan Babuljak

First, religions are marked by traditionalism.[1] King suggests that religions are inherently conservative and traditional because devotees continually find strength and guidance in the original creative action recorded by the religion. Whether it is the life and works of an individual founder or the words of foundational sacred scriptures, these original actions and words function as models of pristine purity, for faithful living, and of power. Believers often look back to the original scriptures or actions and words of the founder for guidance and direction in the contemporary world. These original actions and words are fully authoritative for the believing community. How do devotees make sense of changing social or cultural conditions? What are the sources of knowledge that they utilize to navigate their world? The sources for religious people lie in the religious traditions themselves. Indeed, Christian churches are often modeled on a “New Testament model” of the church. It would be strange for a church today to be modeled on a “medieval model” of church, since the paradigm of church was established in the New Testament. Reform movements seek to reform the religion in terms of its more holy past, for example, to “be the New Testament church.”

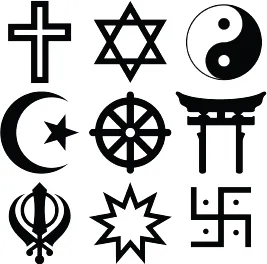

Second, religions employ myth and symbol. Myths are stories about the origins of life. As such, myths serve an explanatory function—they explain all kinds of things, such as the creation of the universe, the emergence of human beings, and the origins of disease and death. Symbol is the language of myth, for myths are saturated with heavily symbolic meaning. Ordinary language simply cannot fully communicate a religion’s truth, so symbolic language is necessary. Symbols can be linguistic or physical. Linguistic symbols consist of words, or discourse, that communicate more than their literal, surface meaning. Physical symbols point beyond themselves to communicate insights of the religion. To a Christian, a cross is not just two intersecting lines but rather conjures up the cost of salvation.

Myth narrates a sacred history; it relates an event that took place in primordial Time, the fabled time of the “beginnings.” In other words, myth tells how, through the deeds of Supernatural Beings, a reality came into existence, be it the whole of reality, the Cosmos, or only a fragment of reality—an island, a species of plant, a particular kind of human behavior, an institution. Myth, then, is always an account of a “creation”; it relates how something was produced, began to be. Myth tells only of that which really happened, which manifested itself completely.

Eliade, Myth and Reality, 5–6

Third, religions promote concepts of salvation, liberation, and release. Winston King notes that all religions claim to save people from and to something. Religions presume that all kinds of problems need to be surmounted, and that a paradise, heaven, better existence, or even nonexistence awaits those who faithfully follow a particular religion. The promise of deliverance powerfully motivates people to adhere to the tradition and can be a source of courage in the face of tragedy or other personal or corporate trial. Additionally, each tradition offers the specific ways that one can be saved into paradise or at least out of the suffering of existence. Consequently, believers can spend much energy learning to live according to their religious tradition, with the hope of being delivered from the troubles of their present condition.

Figure 1.4. Religious symbols. First row: Christian cross, Jewish Star of David, Taoist Yin Yang. Second row: Islamic star and crescent, Buddhist wheel of dharma, Shinto torii. Third Row: Sikh khanda, Baha’i star, Jain swastika.

Wikimedia Commons

Fourth, religions offer sacred places and sacred objects. The idea of the sacred denotes being set apart, a separation from and discontinuity with the surrounding world, from that which is ordinary, mundane, routine. Some areas and objects are considered special, set apart from ordinary areas and objects. Often physical actions accompany the entrance into the sacred place, for example, bowing, removing footwear, kneeling. The handling of sacred objects is not to be done casually but is usually accompanied by special words, chanting, or physical performance. Demarcating sacred places and objects are different types of boundaries that function to separate human beings from the sacred.

Figure 1.5. A nkisi nkondi (power figure) from Kongo Central Province in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. A nkisi nkondi serves as a container for potent ingredients used in magic and medicine. A ritual expert activates the figure by breathing into the cavity of the abdomen and immediately seals it off with a mirror. Nails and blades are driven into the figure, either to affirm an oath or to destroy an evil force.

Brooklyn Museum/Wikimedia Commons

Boundaries of the sacred can be physical, ritual, and psychological. Crossing these boundaries requires some form of action on the part of the devotee. Physical boundaries, such as gates, doors, and curtains, require that one physically cross from the ordinary to the sacred space by passing through them. Ritual boundaries, such as bowing and kneeling or washing with water prior to entering the sacred place or encountering the sacred object, have a performative role in preparing an individual or community to communicate with the divine. And psychological boundaries entail recognition that since one is encountering the sacred, one must be prepared emotionally and psychologically, which is usually accompanied by the need to purify oneself, say, through confession or repentance, before facing the sacred.

Allah made the Ka’ba [Qa’abah], the Sacred House, a means of support for men, as also the Sacred Months, the animals for offerings, and the garlands that mark them: that you may know that Allah has knowledge of what is in the heavens and on earth and that Allah is well-acquainted with all things.

Qur’an 5:97[2]

Fifth, religions employ sacred actions (rituals). Human beings are ritual beings. So much of our lives is ritualistic, whether for sacred or communal ends, and we participate in ritual action in all sorts of ways. Ritual involves order and usually has a communicative function. Generally, rituals communicate something, either to a transcendent being or to other human beings. Rituals involve elements of order, routine, and a commonly accepted set of meanings, although specific rituals do not require universal acceptance. If you have traveled outside your own country or state, you quickly recognize that there are a host of ritual activities that need to be learned in order to avoid offending others. Ritual and culture are closely related. Moreover, ritual actions can be simple or complex, sacred or mundane. And they can involve stylized sayings or chanting, bowing, kneeling, or sacrifices (e.g., of animals, vegetables, money).

Since sickness is the action of spirit, therapeutic action is sacramental. The sickness is only a symptom of the spiritual condition of the person, which is the underlying cause of the crisis, and it can only be cured by expiation—sacrifice—for the sin which has brought it about. This, then is a further characteristic of sin. It causes physical misfortune, usually sickness, which is identified with it, so that the healing of the sickness is felt to be also the wiping out of the sin.

Evans-Pritchard, Nuer Religion, 192

Ritual action pervades all communities, whether modern or traditional, urban or rural. We engage in simple ritual behaviors in our daily lives. When we enter an elevator, how do we act and move, and what do we say or not say? After entering an elevator, we immediately turn around—it would not seem quite normal to enter the elevator and remain facing the rear of the elevator whe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Endorsements

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- 1. The Persistence of Religion

- 2. Hinduism

- 3. Buddhism

- 4. Jainism

- 5. Sikhism

- 6. Taoism and Confucianism

- 7. Judaism

- 8. Christianity

- 9. Islam

- 10. New Religious Movements

- Notes

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

- Back Ad

- Back Cover