- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

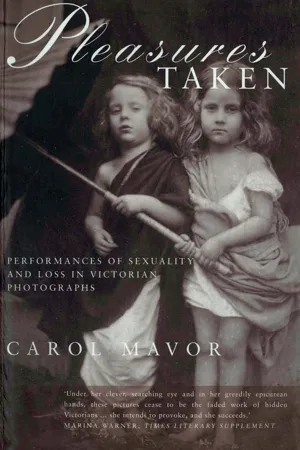

About this book

Lewis Carroll's photographs of young girls, Julia Margaret Cameron's photographs of Madonnas and the photographs of Hannah Cullwick, "maid of all work", pictured in masquerade - Carol Mavor addresses the erotic possibilities of these images, exploring not ony the sexualities of the girls, maids and Madonnas, but the pleasures taken - by the viewer, the photographer, the model - in imagining these sexualities.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pleasures Taken by Carol Mavor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Kunst & Geschichte der Fotografie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

KunstSubtopic

Geschichte der FotografieCHAPTER I Dream-Rushes: Lewis Carroll's Photographs of Little Girls

On March twenty-fifth, 1863, Lewis Carroll (Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, 1832-98) composed a list of 107 names—girls “photographed or to be photographed.” The girls are grouped under their Christian names, all the Alices together, all the Agneses together, and all the Beatrices together, all in alphabetical order. He also notes many of their dates of birth (that telltale sign of a girl’s true girlishness). Carroll’s is a poem of girlhood that rolls off the tongue, like a catalog of Victorian flowers. His prose from the twenty-fifth of March is not unlike one of Humbert Humbert’s most cherished poems, Lolita’s class list, a poem that Humbert took the pains to memorize by heart:

A poem, a poem, forsooth! So strange and sweet was it to discover this “Haze, Dolores” (she!) [Lolita’s full name] in its special bower of names, with its bodyguard of roses—a fairy princess between her two maids of honor. I am trying to analyze the spine-thrill of delight that it gives me, this name among all of the others. What is it that excites me almost to tears (hot, opalescent, thick tears that poets and lovers shed)? What is it? The tender anonymity of this name with the formal veil (“Dolores”) and that abstract transposition of first name and surname, which is like a pair of new pale gloves or a mask?1

Very few critics have been willing to touch the little girls Carroll photographed. The subject makes them understandably uneasy. When they do touch upon the topic of his curious photographs, they tend to read not the pictures themselves, or the situation of the girl of the period, but rather Carroll. They want to make it clear that Carroll was not a Humbert Humbert.

Helmut Gernsheim, for instance, who was the first to seriously acknowledge the pictures as important to the history of photography and who has written the definitive book on Carroll’s photographs, clearly seeks to minimize conflict when confronting the troubling images: “Beautiful little girls had a strange fascination for Lewis Carroll. This curious relationship, . . . may be described as innocent love.”2 Similarly, Morton Cohen, the man responsible for publishing the long-lost nude photographs taken by Carroll, argues that Carroll was “drawn naturally to them; he revelled in their unaffected innocence, their unsophisticated, unsocialized simplicity; he worshiped their fresh, pure unspoiled beauty” and was “far from being James Joyce’s ‘Lewd Carroll’ or having anything in common with Vladimir Nabokov’s Humbert Humbert.”3

Cohen’s emphasis on purity, innocence, and simplicity is peculiar when one considers what Carroll suggested about childhood in his own letters and diaries and in the Alice books themselves. Many of Carroll’s letters revel in the sadistic desires of children, as Carroll-as-child takes sides with all of the girl-children of the world, battering his auditor with questions as only children (usually) do.4 Likewise, Alice may try to be polite in Wonderland, but she is downright rude when she goes through the Looking Glass, and Carroll even refers to Alice as “Malice” in a letter to one of his child-friends. James Kincaid points out the maliciousness of children and the impossibility of valuing innocence: “[In the Alice books] there is often present a deeper and more ironic view that questions the value of human innocence altogether and sees the sophisticated and sad corruption of adults as preferable to the cruel selfishness of children.”5 The success of Kincaid’s useful analysis is not all that surprising; the literary texts on Carroll are generally more satisfactory than those that focus on the photographs. Although the difference between the critical texts is partly due to different emphases within respective disciplines and factions, it is also a matter of confronting the nonfictional Alices—the real Alice Pleasance Liddell and all of her successors. Critics such as Cohen try to veil the obvious sexuality that Carroll captured on the photographic plates. Even more than the stories, the pictures “question the value of human innocence”—both Carroll’s and his models’.

Cohen argues that Carroll was not of the stern evangelical tradition that informed the rearing of many children but, rather, inherited his approach to the child from romantic forebears, who “assumed that the child came into this world innocent and pure.”6 For Carroll (according to Cohen), the child, especially the female child, was divine, pure, good. Moments of Cohen’s analysis are convincing, but he is unreasonably insistent upon washing out any contradictions. At the heart of the argument is not Carroll but Cohen’s own desire to form a general theory of Carroll’s sexuality. Cohen is interested in presenting Carroll as “repressed” by Victorian culture, and therefore innocent: “Only as a repressed human being could he have lived his paradoxical life and worshipped the young girls with a clear, Christian conscience.”7 What Cohen fails to see is how he in turn is repressed by our own society, and how this repression governs his reading of Carroll.

Confronted by the taboo combination of child and sexuality, such critics refuse to “see.” In Foucauldian terms, participants in the tradition of modern sexual discourse feel the need to discuss sex in a way “that would not derive from morality alone but from rationality.”8 Thus while Carroll himself could lead a double-double life as photographer and clergyman, mathematician/logician and author of nonsense, Cohen forms a rational discourse that blocks our way to confronting the contradictions that the pictures play out. In the discussion of evangelical versus romantic, the difficulty actually lives with the depiction of the girls; like most observers of Carroll’s pictures, Cohen renders the models as silent and even invisible, solving Carroll’s problem by denying the children’s sexuality. In Cohen’s words, “Victorian parents who shared Dodgson’s views allowed their innocent offspring to romp about in warm weather without any clothes on, particularly at the seaside, and were quite accustomed to seeing nude ‘sexless’ children used as objects of decoration in book illustrations and greeting cards.”9 The telltale words here are “used,” “objects,” and “decoration.” (And is there no difference between playing on the beach and sitting nude before a man and his lens in his studio?) But the larger question still remains: Why do we have to insist that children have no sexuality? In pronouncing Carroll’s romanticism, Cohen reveals himself to be a latter-day evangelical, trying to protect his own children (his life’s work on Carroll) from falling into evil ways. Ironically, whereas Cohen remarks critically of evangelical children that they “could hardly be thought to have any freedom . . . these children had to be transmogrified from wicked things into beings of goodness and godliness,” Cohen’s “children” also lack the freedom of displaying sexuality.10

The word “sexuality,” indeed, was born at the dawn of the nineteenth century (in 1800) and originally referred only to biology; it was crystallized into its current meaning in 1879, when J. Matthews Duncan used the term to mean (as defined in the Oxford English Dictionary) a “possession of sexual powers, or capability of sexual feelings.”11 Duncan reminded his readers that “in removing the ovaries you do not necessarily destroy sexuality in a woman”—a distinction between sexuality and reproduction that Sigmund Freud also drew (in “The Sexual Life of Human Beings”), this time with specific references to children:12

To suppose that children have no sexual life—sexual excitations and needs and a kind of satisfaction—but suddenly acquire it between the ages of twelve and fourteen, would (quite apart from any observations) be as improbable, and indeed senseless, biologically as to suppose that they brought no genitals with them into the world and only grew them at the time of puberty. What does awaken in them at this time is the reproductive function, which makes use for its purposes of physical and mental material already present. You are committing the error of confusing sexuality and reproduction and by doing so you are blocking your path to an understanding of sexuality.13

Problematic as Freud’s readings are, and problematic as it is to use his work in any kind of historical analysis (particularly one outside of his own period and culture), he nonetheless remains useful to a discussion like the one at hand—in part, as art historian Griselda Pollock has pointed out, because he gave us a language in which to talk about sexuality.14 In particular, we may use this language to talk about sexuality’s connection to theories of difference, which, as we shall see, become especially relevant to Carroll’s photographs of little girls. Freud not only accelerated the discourse on male and female sexual difference but also acknowledged both that children are sexual and that they are sexual in a way different from adults. According to him, childhood sexuality is an “instinct” that has been tamed by the time we reach adulthood. To be sure, Freud is essentializing children, and he exacerbates this problem (again in “The Sexual Life of Human Beings”) when he equates the child’s sexuality with that of the “primitive,” the “pervert,” and so on. But what is salvageable for our purposes is that Freud alerts us to the ways in which we have been educated into thinking that children are pure, asexual, and innocent, and to how “anyone who describes them otherwise can be charged with being an infamous blasphemer against the tender and sacred feelings of mankind.” 15 I am proposing to be blasphemous: to acknowledge the sexuality of children (and of the Victorian girl at that) while making every attempt not to project our oppressive desires onto their bodies—an impossible goal, of course.

Venus of Oxford

Carroll’s first reference to photographing a nude child is in a diary entry dated May 11, 1867: “Mrs. L. brought Beatrice, and I took a photograph of the two; and several of Beatrice alone, ‘sans habilement [sic].’”16 Beatrice Hatch was one of Carroll’s favorite models, along with her sister Evelyn; both were at ease in what Carroll has referred to as their “primitive dress.” Of the four nude images that have been rediscovered, we are most surprised by the image of Evelyn Hatch (c. 1878, fig. 3).17 She catches our eye and confronts us with her own gaze (not unlike Manet’s Olympia, 1863) as she lies before us sprawled as a tiny odalisque. As childwoman, posed like a courtesan, Evelyn reminds us also of Titian’s Venus of Uibino (1538)—not only in her pose but also in the treatment of the photograph, which gives it its Venetianesque quality. It is a portmanteau of a “real” photograph and layers of opalescent colors. Precious Evelyn has been “printed on emulsion on a curved piece of glass, with oil highlights applied to the back surface. Beneath it is a second piece of curved glass painted in oil.”18 Curved glass, caressed with paint, all taboo: this “paintograph” is worthy of serious fetishization.19 Evelyn’s body glows in a flesh-colored light that gives way to a surrealistically painted marsh of golden moss-greens. Evelyn, stuck in an everlasting sunset, which is strangely muted by the peculiar pink-yellows that shine below the rather ominous dark violet light, is a modern little Venus of Oxford.

Evelyn is also part animal. Her eyes, mildly vampirish, shine like a fox’s at night. A closer look reveals tiny highlights that have been painted on the picto-glass, as if her eyes were marbles. Her face, painted darker than the rest of her pure girl-body, indeed gives the sense that Evelyn, like Alice’s pig-baby, is part animal and part child. Nina Auerbach has also equated Evelyn with animality, specifically a kind of animal sexuality. In the current Carroll scholarship, Auerbach’s is the only discussion that confronts this image:

Figure 3. Lewis Carroll, Portrait of Evelyn Hatch, c. 1878. (The Rosenbach Museum and Library, Philadelphia and The Executors of the C. L. Dodgson Estate)

Some embarrassed viewers have tried to see no sexuality in these photographs, but it seems to me needlessly apologetic to deny the eroticism of t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER I DREAM-RUSHES

- CHAPTER II TO MAKE MARY

- CHAPTER III TOUCHING NETHERPLACES

- CONCLUSION

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX