CHAPTER 1

TQM and Hoshin Kanri

Japanese quality control in its present form is based on the statistical quality control (SQC) that was brought over from the United States after World War II. Later in Japan we developed total quality control (TQC), which in other countries has come to be known as CWQC (companywide quality control) or TQM (total quality management).

The transition from SQC to TQC occurred during the years 1961 to 1965 in companies whose achievements in quality earned them the Deming Prize. These companies were Nissan Automotive (1960), Teijin and Nippon Denso (1961), Sumitomo-Denko (1962), Nippon-Kayaku (1963), Komatsu (1964), and Toyota Jiko (1965). During this period the concepts of control items and hoshin kanri, or policy deployment, were born.

It was also during these years that the emphasis in industry shifted from chemicals to mechanical assembly of automobiles and home appliances. Because of this, new products were needed in rapid succession, and this required establishing quality standards throughout the entire system, beginning with the product planning stage. SQC centered on production evolved naturally into TQC.

The official introduction of TQC to Japan was a one-year series of TQC seminars held in 1960 for SQC magazine. Dr. Feigenbaum, who led those seminars, defined TQC as an effective system for integrating the development of quality among various parts of a company, quality retention and quality improvement for economical production, and service that considers its goal to be complete satisfaction of consumers.

This definition of TQC does not allow for the involvement of staff, management, and other workers, and until recently, such involvement was indeed absent, at least in the United States. However, the Japan Standards Association and the Union of Japanese Scientists and Engineers (JUSE) have held seminars for various levels in the organization — including top management, department and section heads, staff, supervisors, and QC circle leaders — so that in companies where TQC has been introduced in this country, it is deployed as a means of securing quality accountability at each of these levels. Thus, a CWQC peculiar to Japan has evolved.

Hoshin kanri, also known as hoshin planning or management by policy or (as we will refer to it here) policy deployment, has its origins in SQC. In 1958 the following audit items were introduced into the Deming Prize: policy and plan, organization, interdepartmental relationships, standardization, analysis, control, and effects. Applications submitted for prize examination were therefore required to contain descriptions of TQC promotion policy or company policy. This was an important factor in emphasizing policy in quality control.

The present-day significance of hoshin kanri is exemplified by Komatsu’s control point setting chart and Nokawa Shoji’s flag method. Nokawa’s method, based on the control item list of Teijin Company in 1961 and the concepts of control items and inspection items practiced at Nippon-Kayaku, offered a specific method for target deployment. The “integrated control system chart” (N. Kitahata, 1964) contains information useful to many issues still being discussed today. The term hoshin kanri was not used at that time but the same control system we use today was in action then.

Hoshin kanri is just one of the pillars of TQM.* Others, such as production control and cost control, are in operation daily in every company. These daily controls are the basis of business management. To survive within the dynamic environments of social, economic, and technological change, however, a company must use strategic management to respond to competitive situations. Maintaining the status quo amounts to regression, so companies must develop. To do this, they need to clarify both the apparent and the intangible weaknesses of their systems so that these weaknesses are eliminated and the overall systems improved. This is what makes policy deployment so important: It clarifies specific annual target policies derived from the long- and medium-term policies that encompass the long-term visions of the company. It strives to achieve targets through action plans intended to improve the control system. These action plans are then deployed for their targets and their policies. Meanwhile, actions such as Quality Assurance (QA) need to be in permanent motion since they involve daily activities more than does policy deployment. Daily activity is the basis of policy deployment, which improves the level of the QA activities as Feigenbaum defined them; but such companywide improvement activities at all levels of an organization are just one feature of TQM.

Hoshin Kanri and Target Control

Target control was proposed by E. C. Schleh (1963) as “management by results” and is based on scientific action. The concept originated in social psychology and emphasizes motivating people to achieve targeted goals. Under its volunteer approach, workers set up purposes and work toward their achievement.

When the concept of target control was introduced to the Japanese in 1963, it immediately appealed to management. Because it could be implemented easily, it soon grew popular in Japan. Target control emphasizes results, but today the process that produces these results must also be analyzed. Thus, TQM looks for the process that produces bad results. Bad results come about because of certain factors. You could define the process that produces bad results as a conglomeration of many factors. In TQM you look for the true factors. You collect data so that any action you take is based on facts rather than on ideology. The data must be analyzed so that the factors are grasped scientifically and can thus be eliminated as obstructions to the achievement of desired results. That is why methods such as statistical analysis are still in use today.

For hoshin kanri in TQM, the plan-do-check-action (PDCA) cycle is the most important item of control. In this cycle you make a plan that is based on policy (plan); you take action accordingly (do); you check the results (check); and if the plan is not fulfilled, you analyze the cause and take further action by going back to the plan (action).

The PDCA cycle is important in setting up the policy itself, as well. The variance between the plan and the actual situation is evaluated each business term or annually, and the cause of such variance analyzed, with the results incorporated into next year’s policy. Here you do not look at the value of the results but at the variance between the plan and the actual situation. If the cause is not clarified, then the same discrepancy could appear in the next period as well. The process that produced the bad results obviously has some weaknesses, and these need to be discovered and eliminated. You emphasize the process rather than the results and improve the process to achieve better results. This approach, hoshin kanri or policy deployment, is distinctly different from Schleh’s target control, although in the early days of TQC the two terms were often used interchangeably.

Target can be defined as “expected results.” Means can be defined as “guidelines for achieving a target.” The means show how to achieve the target, in other words.

Generally, policy is used in the broadest sense, so that a target and means combined can be called a policy. If the means show the direction, then you clarify the

specific steps for achieving the target by basing them on these means. Then you can determine an action plan with a timetable.

“Reduction in rejection rate” is neither an implementation item nor a means. It is a target. How to reduce the rejection rate is important, however, and the specifics related to them are action items. To improve on expected results you must discover weaknesses in the processes that produce these rejects. Means show the way to discover and eliminate those weaknesses. Examples of means are “thorough process analysis” or “promotion of standardization.” Specific corrective actions will emerge after data based on such means have been analyzed.

An action plan for improvement should not be bogged down in detail. Plans will become increasingly detailed with each year-end analysis of variance. However, since plans are usually set on timetables of six months or a year, they tend to be broadly stated as well. You may need to add an action plan chart for additional implementation items as the improvements progress.

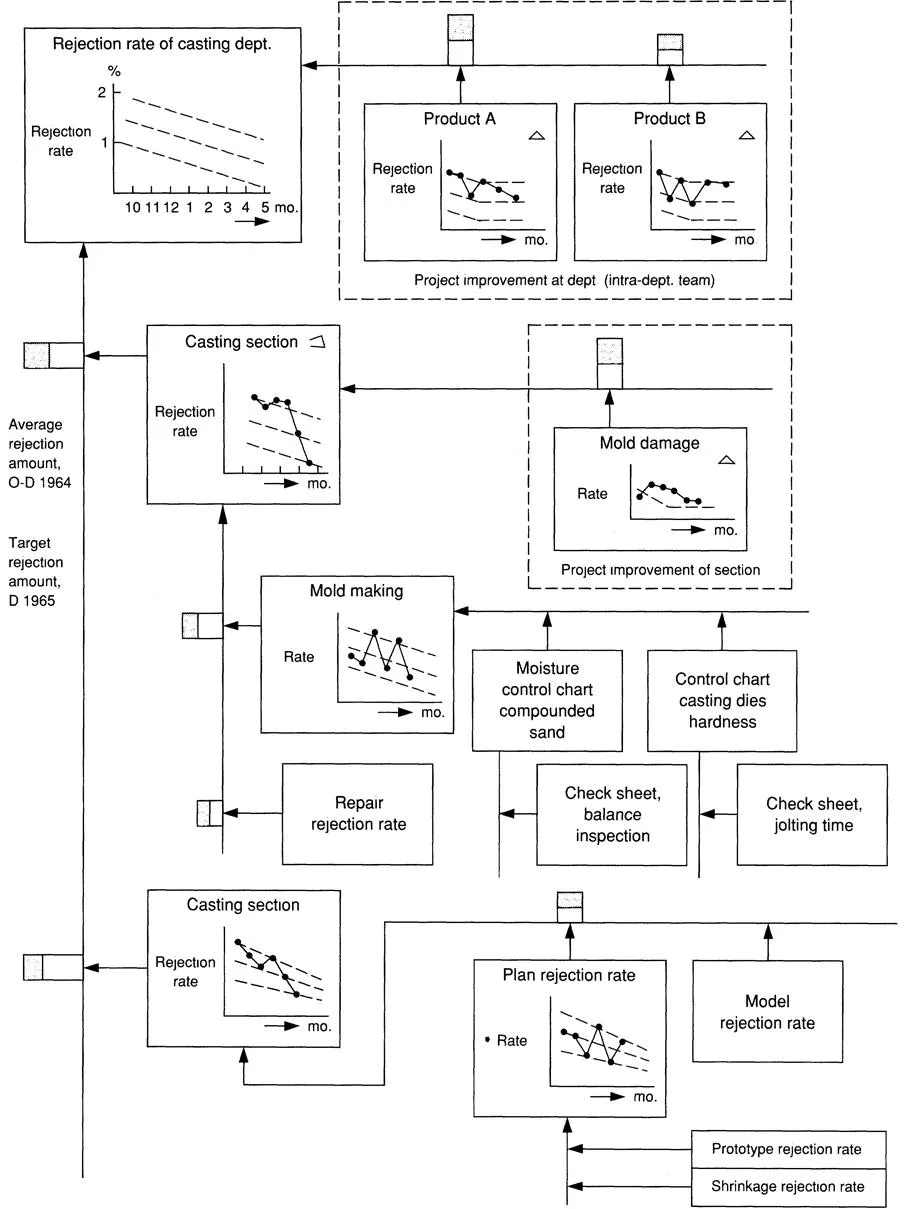

The best method for target deployment currently is the flag* method (Figure 1-1). It combines a Pareto analysis chart and a fishbone diagram.

First, Pareto analysis is made for the section’s rejection rate (upper left). The department head establishes a target for reducing rejections and then meets with section heads to set up section targets. Here, a major improvement is added to the major rejection item. Exercise caution here. An across-the-board reduction of 5 percent, for example, fails to address priorities, while a 3 percent reduction in an already-low rejection rate is nonsense. In the latter case, you should shoot for zero or for maintaining the current percentage.

Next, you make a Pareto deployment for each group and establish targets for group leaders. This corresponds to target deployment in a normal organization. Pareto deployment for each product based on a control graph of the department head becomes the target deployment for the project team representing each product. In a nonstandard organization, a Pareto deployment and the resulting target per phenomenon at the section or group can become a target for deployment for the QC team (shown by the dotted frames in Figure 1-1). Members that are necessary are called in to these teams, crossing the boundaries of departments in order to analyze the corrective actions, make standards, and prevent repetition. Then the team is dissolved.

The same type of deployment used for targets can also be used for means. For example, to raise the level of QA actions, you need to address the following items:

• Enhance process control

• Improve the process

• Control through use of enhanced inspection and control charts

• Control through promotion of quality and improvement of process deployment capability

This deployment method can be applied to the action plan of a department or section, a plan based on the action items relevant to that department or section at each stage and adapted to t...