- 520 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Marine glycobiology is an emerging and exciting area in the field of science and medicine. Glycobiology, the study of the structure and function of carbohydrates and carbohydrate-containing molecules, is fundamental to all biological systems and represents a developing field of science that has made huge advances in the last half-century. This book revolutionizes the concept of marine glycobiology, focusing on the latest principles and applications of marine glycobiology and their relationships.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Marine Glycobiology by Se-Kwon Kim in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Biotechnology in Medicine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

MedicineSubtopic

Biotechnology in Medicinesection six

Marine carbohydrates

chapter fifteen

Polysaccharides from marine sources and their pharmaceutical approaches

Sougata Jana, Arijit Gandhi, and Subrata Jana

Contents

| 15.1 | Introduction | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15.2 | Production of polysaccharides by marine sources | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15.3 | Major marine polysaccharides

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15.4 | Other marine polysaccharides

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15.5 | Future directions | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15.6 | Conclusion | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| References | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

15.1Introduction

Marine resources are nowadays widely studied because the oceans cover more than 70% of the world’s surface. Among the 36 known living phyla, 34 are found in marine environments with more than 300,000 known species of fauna and flora. The rationale of searching for bioactive compounds from the marine environment stems from the fact that marine plants and animals have adapted to different types of marine environment and these creatures are constantly under tremendous selection pressure including space competition, predation, surface fouling, and reproduction Kijoa and Swangwong 2004, Yan 2004, Jana et al. 2013b). The marine environment covers a wide thermal, pressure, and nutrient range, and it has extensive photic and non-photic zones. This wide variability has facilitated extensive specification at all phylogenetic levels, from microorganisms to mammals. Despite the fact that the biodiversity in the marine environment far exceeds that of the terrestrial environment, research into the use of marine natural products as pharmaceutical agents is still in its infancy. This may be due to the lack of ethnomedical history and the difficulties involved in the collection of marine organisms. But with the development of new diving techniques, remotely operated machines, and so on, it is possible to collect marine samples; in fact, during the past decade, over 4200 novel compounds have been isolated from various marine animals such as tunicates, sponges, soft corals, bryozoans, sea slugs, and marine organisms (Harvey 2000, Proksch et al. 2002, Jha and Zi-Rong 2004, Jirge and Chaudhari 2010).

Among the different bioactive compounds obtained from the sea, polysaccharides have been gaining interesting and valuable applications in the food and pharmaceutical fields. As they are derived from natural sources, they are easily available, nontoxic, cheap, biodegradable, and biocompatible. Polysaccharides can be obtained from a number of sources including seaweeds, plants, bacteria, fungi, insects, crustaceans, and animals, and can be structurally tuned through genetic engineering. The term “polysaccharide” encompasses very diverse and large carbohydrates that may be composed of only one kind of repeating monosaccharide (termed homo-polysaccharides or homoglycans; e.g., cellulose) or formed by two or more different monomeric units (hetero-polysaccharides or heteroglycans; e.g., agar, alginate, carrageenan). The conformation of the polysaccharide chains is markedly dependent not only on the pH and ionic strength of the medium, particularly in the case of polyelectrolytes, but also on the temperature and the concentration of certain molecules. Polysaccharides are divided into two subtypes: anionic and cationic. Several anionic and cationic polysaccharides are widely available in nature and have gained keen interest in the food and pharmaceutical fields (Colquhoun et al. 2001, Guezennec 2002, Coviello et al. 2007, D’Ayala et al. 2008). The biological activity of naturally occurring polysaccharides has been increasingly utilized for human applications and creating a strong position in the biomedical field. Because of their different chemical structures and physical properties, these natural sources can be used in the different applications, from tissue engineering to the preparation of drug vehicles for controlled release. This chapter focuses on the present use and the diverse applications of marine polysaccharides in the pharmaceutical sector.

15.2Production of polysaccharides by marine sources

The polysaccharide content of marine sources varies greatly in brown and red algae. Polysaccharides may comprise up to 74% of the total organic matter (Romankevich 1984), while they range from 20% to 40% in planktonic algae (Parsons et al. 1961), and the content in zooplanktons is two to four times lower than that in phytoplanktons. Phytoplanktons serve as the principal source of polysaccharides found in seawater, particles, and sediments; the photosynthetic conversion of carbon dioxide to biomass is the basis of polysaccharide production. Phytoplankton polysaccharides’ composition has been surveyed in both field samples and laboratory monocultures. In general, glucose has been found to be the most common monosaccharide, probably due to the fact that phytoplanktons store polysaccharides primarily in the form of glucose. The major source of polysaccharides in marine sediments is sinking particles. Methods of analysis of polysaccharides in sediments usually involve extraction, separation, and, finally, quantitation of the sugars. Polysaccharides in sediments comprise ~10% of the total organic carbon. Studies of anoxic surface sediments show that amino acids and polysaccharides are the major constituents of organic matter (Burdige and Zheng 1998). Polysaccharides are remineralized rapidly during epigenetic and digenetic bacterial activity, and only less than 10% of these compounds are stable enough to be incorporated into the sediment a few centimetres below the sediment/water interface (Degens et al. 1964, Seifert et al. 1990).

15.3Major marine polysaccharides

15.3.1Chitosan

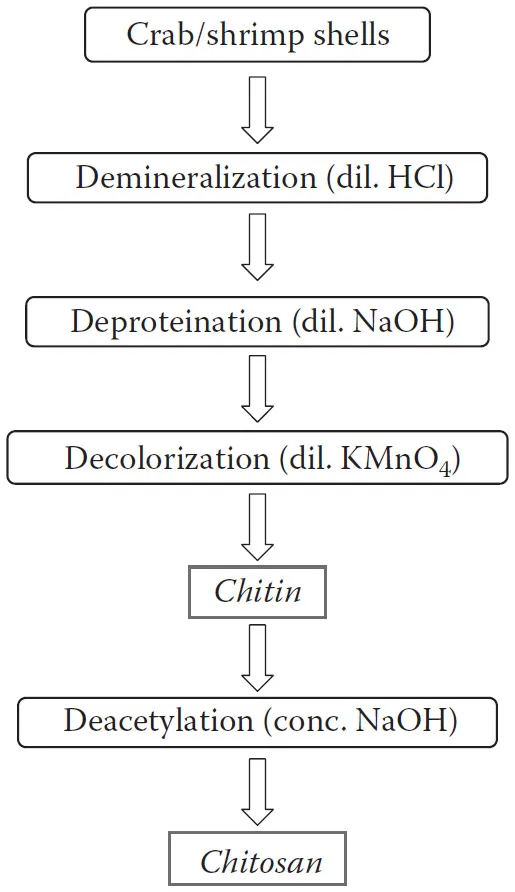

Chitin and chitosan have wide applications in the medical field, such as wound dressing, hypocholesterolemic agents, blood anticoagulant, antithrombogenic agents, and drug delivery systems, in addition to other uses such as wound-healing materials and cosmetic preparations. Chitosan and its derivatives have been studied extensively as carriers for drug delivery, cancer therapy, and in the biomedical field, and is generally regarded as safe materials. Chitin is a known biodegradable natural polymer based on polysaccharides, and is obtained from crustacean shell (e.g., crabs, shrimps, and lobsters) and fungi such as yeasts and plants. It principally occurs in animals of the phylum Arthopoda (Knaul et al. 1999, Zheng et al. 2001). In 1823, Ojer named it “Chitin” from Greek word “khiton,” meaning “envelope,” present in certain insects. In 1894, Hope Seyle named it as “chitosan.”

15.3.1.1Chemical structure

Chitosan is a linear copolymer consisting of B (l-4)-linked 2-amino-2-deoxy-D-glucose (d-glucosamine) and 2-acetamido-2-deoxy-D-glucose (N-acetyl-D-glucosamine) units (Figure 15.1). Chitosan is the second most abundant natural polymer after cellulose, and is obtained by alkaline N-deacetylation of chitin, which is the primary structural component of the outer skeletons of many marine creatures such as crustaceans, crabs, shrimp shells, and many other species such as insects and fungi (Addo et al. 2010, Jana et al. 2013b). Chitosan is degraded by lysozyme present in the various mammalian tissues, which leads to the production of N-acetyl-D-glucosamine and D-glucosamine, which also play an important physiological role in the in vivo biochemical processes.

15.3.1.2Method of manufacture

Chitosan is manufactured by chemically treating the shells of crustaceans such as shrimps and crabs (Figure 15.1).

Figure 15.1 Chitosan production flow diagram.

The process involves the separation of proteins by treating with alkali and of minerals such as calcium carbonate and calcium phosphate by treatment with acid. Initially, the shells are deproteinized by treatment with 3%–5% aqueous sodium hydroxide solution. The resulting product is neutralized, and calcium is removed by treatment with 3%–5% aqueous hydrochloric acid solution at room temperature to precipitate chitin. The chitin is dried and deacetylated to give chitosan. This can be achieved by treatment with 40%–45% aqueous sodium hydroxide solution at moderate temperature (110°C), and the precipitate is washed with water. The crude sample is dissolved in 2% acetic acid and the insoluble material is removed. The resulting clear supernatant solution is neutralized with aqueous sodium hydroxide to give a white precipitate of chitosan. It can be further purified and ground to a fine, uniform powder or granules (Gupta and Ravikumar 1986, Niederhofer and Maller 2004, Jana et al. 2013b).

15.3.1.3Properties of chitosan

The degree of N-deacetylation (40%–98%) and molecular weight (50,000–2,000,000 Da) play very important roles in the physicochemical properties of chitosan. Hence, they have a major effect on the biological properties.

Figure 15.2Chitosan is a linear polysaccharide composed...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Editor

- Contributors

- Section I: Introduction to marine glycobiology

- Section II: Marine glycoconjugates of reproduction and chemical communications

- Section III: Marine glycans

- Section IV: Marine glycoproteins

- Section V: Marine glycoenzymes

- Section VI: Marine carbohydrates

- Section VII: Bioinformatics of glycobiology

- Section VIII: Biological role of glycoconjugates

- Section IX: Glycoconjugates in biomedicine and biotechnology

- Index