- 536 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Electronic, Magnetic, and Optical Materials

About this book

This book integrates materials science with other engineering subjects such as physics, chemistry and electrical engineering. The authors discuss devices and technologies used by the electronics, magnetics and photonics industries and offer a perspective on the manufacturing technologies used in device fabrication. The new addition includes chapters on optical properties and devices and addresses nanoscale phenomena and nanoscience, a subject that has made significant progress in the past decade regarding the fabrication of various materials and devices with nanometer-scale features.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Electronic, Magnetic, and Optical Materials by Pradeep Fulay,Jung-Kun Lee in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias físicas & Ingeniería eléctrica y telecomunicaciones. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

1.1 INTRODUCTION

The goal of this chapter is to recapitulate some of the basic concepts in materials science and engineering as they relate to electronic, magnetic, and optical materials and devices. We will learn the different ways in which technologically useful electronic, magnetic, or optical materials are classified. We will examine the different ways in which the atoms or ions are arranged in these materials, the imperfections they contain, and the concept of the microstructure–property relationship. You may have studied some of these—and perhaps more advanced—concepts in an introductory course in materials science and engineering, physics, or chemistry.

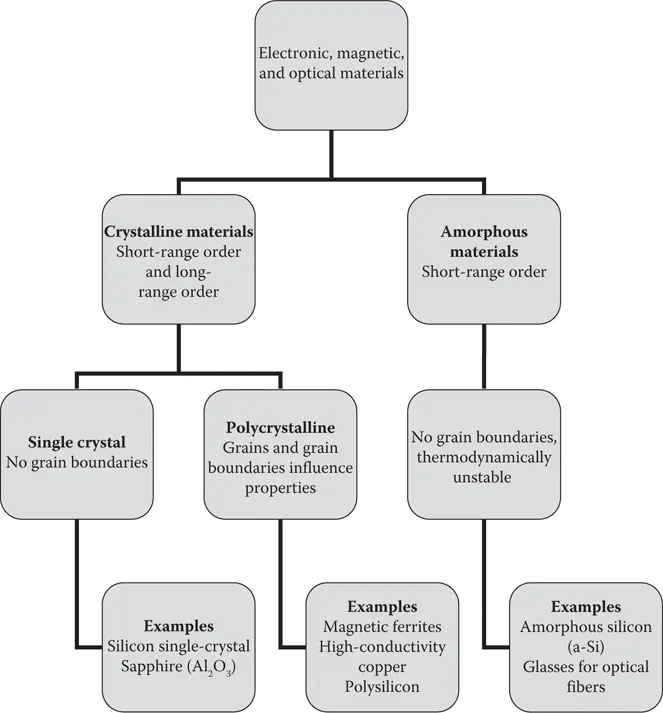

1.2 CLASSIFICATION OF MATERIALS

An important way to classify materials is to do so based on the arrangements of atoms or ions in the material (Figure 1.1). The manner in which atoms or ions are arranged in a material has a significant effect on its properties. For example, Si single crystals and amorphous Si film are made of same silicon atoms. Though their compositions are same, they exhibit very different electric and optical properties. While single crystal Si has higher electric carrier mobility, amorphous Si exhibits higher optical band gap. This is because of different Si atom arrangement. While atoms are perfectly aligned in single crystals, they are randomly distributed in amorphous film.

1.3 CRYSTALLINE MATERIALS

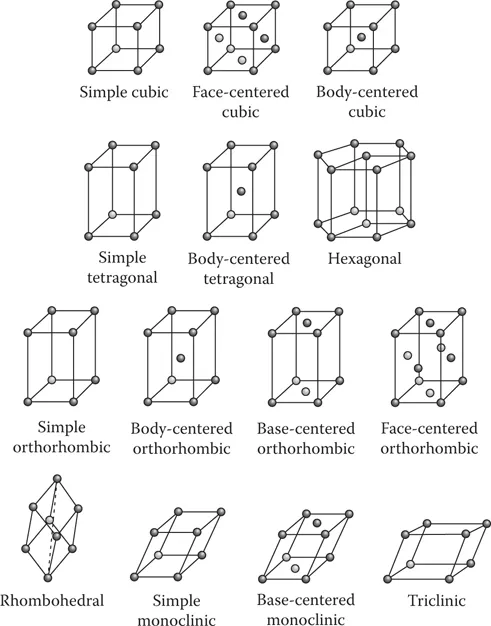

A crystalline material is defined as a material in which atoms or ions are arranged in a particular order that repeats itself in all three dimensions. The unit cell is the smallest group of atoms and ions that represents how atoms and ions are arranged in crystals. Repetition of a unit cell in three dimension leads to the formation of a three-dimensional crystal. The crystal structure is the specific geometrical order by which atoms and ions are arranged within the unit cell. Crystal structures can be expressed using a concept of Bravais lattices, or simply lattices. A lattice is an infinite array of points which fills space without a gap. Auguste Bravais, a French physicist, showed that there are only 14 independent ways of repeatedly placing a basic unit of points in space without leaving a hole. A concept of lattice is analogous to that of a crystal consisting of unit cells (Figure 1.2).

Note that a sphere in Figure 1.2, which is called a lattice point, does not refer to the location of a single atom or ion. The lattice point is a mathematical idea that refers only to points in space, which is applied to several fields of science and engineering. In crystallography, the lattice represents the crystal and the lattice points are associated with the location of atoms and ions. Simply speaking, we can think that either a single atom/ion or a group of atoms/ions occupy a lattice point. When a group of atoms/ions take up the lattice point, their configuration exhibits a certain symmetry around the lattice point. The symmetry of atoms and ions occupying the same lattice point is called basis. A combination of the lattice and the basis determines the crystal structure. In other words:

FIGURE 1.1 Classification of materials based on arrangements of atoms or ions.

We have only 14 Bravais lattices (Figure 1.2). However, there are many possible bases for the same Bravais lattice. The symmetry operation of bases includes angular rotation, reflection at mirror plane, center-symmetric inversion, and gliding, which in turn leads to 230 possible crystal structures out of 14 Bravais lattices. We also have many materials that exhibit the same crystal structure but have different compositions, that is, the chemical makeup of these materials. For example, silver (Ag), copper (Cu), and gold (Au) have the same crystal structure (see Section 1.6).

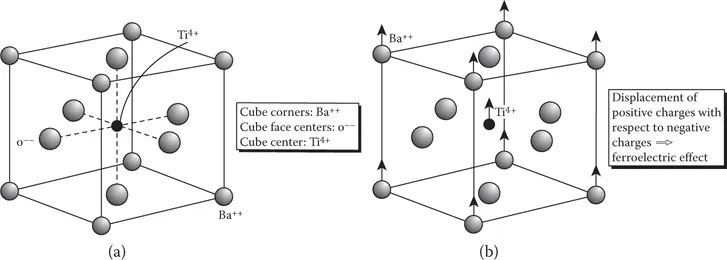

Similarly, materials often exhibit different crystal structures, depending upon the temperature (T) and pressure (P) to which they are subjected. In some cases, changes in crystal structures may also result from the application of other stimuli, such as mechanical stress (σ or τ), electric field (E), or magnetic field (H), or a combination of such stimuli. The different crystal structures exhibited by the same compound are known as polymorphs. For example, at room temperature and atmospheric pressure, barium titanate (BaTiO3) exhibits a tetragonal structure (Figure 1.3). However, at temperatures slightly higher than 120°C, BaTiO3 exhibits a cubic structure, and at even higher temperatures, this structure changes into a hexagonal structure. The different crystal structures exhibited by an element are known as allotropes.

FIGURE 1.2 Bravais lattices showing the arrangements of points in space. (From Askeland, D. and Fulay, P., The Science and Engineering of Materials, Thomson, Washington, DC, 2006. With permission.)

FIGURE 1.3 (a) Cubic and (b) tetragonal structures of barium titanate (BaTiO3). (From Singh, J., Optoelectronics: An Introduction to Materials and Devices, McGraw Hill, New York, 1996. With permission.)

A phase is defined as any portion of a system—including the whole—that is physically homogeneous and bounded by a surface so that it is mechanically separable from the other portions. One of the simplest examples is ice, which represents a solid phase of water (H2O). A phase diagram indicates the phase or phases that can be expected in a given system of materials at thermodynamic equilibrium. The phase diagram also shows a specific condition at which multiple phases coexist. For instance, a stable regime of a liquid phase and that of a solid phase meet at 0°C and 1 atm in the phase diagram of water (H2O) at which both water and ice are found. Thus, amorphous and crystalline materials formed under nonequilibrium conditions are not shown in a phase diagram.

The phase diagram of a binary lead–tin (Pb–Sn) system is shown in Figure 1.4. Three phases, α, β, and L, are seen at different compositions and temperature ranges. The liquidus represents the traces of temperature above which the material is in the liquid phase. Similarly, the solidus is the trace of temperature below which the material is completely solid. In a region between liquidus and solidus lines, both solid and liquid phases are thermodynamically stable. Note that, although most alloys melt over a range of temperatures (i.e., coexistence of liquid and solid phases between the solidus and the liquidus), some specific compositions (e.g., 61.9% tin in the lead–tin system), which are known as eutectic compositions, melt and solidify at a single temperature, which is known as the eutectic temperature. The eutectic...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Authors

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Electrical Conduction in Metals and Alloys

- Chapter 3 Fundamentals of Semiconductor Materials

- Chapter 4 Fermi Energy Levels in Semiconductors

- Chapter 5 Semiconductor p-n Junctions

- Chapter 6 Semiconductor Devices

- Chapter 7 Linear Dielectric Materials

- Chapter 8 Optical Properties of Materials

- Chapter 9 Electrical and Optical Properties of Solar Cells

- Chapter 10 Ferroelectrics, Piezoelectrics, and Pyroelectrics

- Chapter 11 Magnetic Materials

- Index