![]()

1

STRANGE ROOTS

Southern trees bear a strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black body swinging in the Southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

—Lewis Allan

They named it Lynch Street back when it was just a muddy roadway through a black neighborhood in Jackson. Not for the hanging Judge Lynch of Old Virginia, but for an emancipated slave who had done himself proud in Mississippi during Reconstruction.

His name was John Roy Lynch. He was a thin and light-skinned young man with a moustache, self-educated, and just twenty-four when the whites in the state legislature made him Speaker of the House of Representatives. At twenty-six, Lynch became Mississippi’s first black congressman. But he had not come so far by playing Uncle Tom. At the capitol in Jackson, Lynch fought to repeal the “black codes” the Confederates had passed to create a new form of slavery after the Civil War. And in Washington he labored for passage of the 1875 Civil Rights Act. Later, after the whites had turned to the rope and the gun to drive blacks from office in Mississippi, Lynch urged President Grant to send federal troops to protect the freedmen. Grant never did send those troops, and soon Reconstruction and liberty for blacks came to an end in Mississippi. Not long afterwards, the political career of John Roy Lynch also drew to a close. But black Jacksonians remembered that he had never turned his back on them, so they named for Lynch one of the main streets in their city.

A century after John Roy Lynch held office in Jackson, the Second Reconstruction—the civil rights movement of the 1960s—transformed the politics of the Deep South. By 1970 black Mississippians could vote once again, though few held office. And while the street named after Lynch still ran through a black neighborhood, now it was a three-mile stretch of concrete that linked Jackson’s business district with the suburbs to the west, where the whites lived.

For white commuters driving east each morning on their way downtown, the first two miles on Lynch Street seemed just another four-lane corridor through Neon Suburbia. They drove past gas stations, used-car lots, tire stores, and package stores. Past Miller’s Discount Center, the Joy Car Wash, the Cotton Bowl Lanes, Cowboy Maloney’s Appliances, and the Tipsy Kitty Lounge. But the last mile down Lynch Street was different. As the white drivers passed the black, seven-foot-tall letters of a sign that spelled W-O-K-J (“Ebony Radio”), they approached the campus of Jackson State, a black college. Down the dipping, then rising ribbon of white-dotted concrete, they glimpsed two blocks of athletic fields, tall brick dormitories, and classroom buildings. They saw black students carrying books and crossing the road on their way to classes.

Once they left the campus behind, the whites drove down the straight and sloping street through a black neighborhood. To white eyes it looked like a ghetto—five blocks of sleazy beer joints, grimy one-story storefronts, tottering shacks, and glass-strewn gutters. Stopping at a red light, the commuters noticed the old folks on the porches of their rickety wood-frame homes as they fanned away the muggy Mississippi heat. Many of the homes were “shotguns,” long and narrow little cottages of just three rooms without partitions. The saying was that if you fired a shotgun through the open front door, and if the back one was open too, the shot would zip right through and hit nothing. Many blacks in the neighborhood lived in houses like these—with warped shingles and sagging roof peaks—each perched on red-brick piers that shifted in the damp and yellow clay.

In daylight, white drivers on the way home would stare and wonder about these things, and feel little discomfort. But some said that after nightfall it was unwise to drive slowly on Lynch Street.

Still, the blacks living here saw their neighborhood in a different light. To them Lynch Street was not a ghetto. There was little or no prostitution here, no dope-peddling, and no big brick tenements either. Although the poorest blacks lived in row after row of decaying shotguns in the alleys off Lynch Street, a few middle-class blacks owned the tidy white cottages on the street. They planted flowers, shrubs, and vegetable gardens in their small front yards, and kept their lawns mowed. Each Sunday they attended services at one of the neighborhood churches—the Lynch Street Methodist Church, the Mount Calvary Church, or the Pearl Street A.M.E.—where during tense times they could meet to plan civil rights strategy without worrying that police might barge in.

Over the years, small shops had sprung up among the churches, homes, and bars on Lynch Street. Not just because most residents were poor and lacked transportation, but because they preferred to shop in their own neighborhood. Also because some white merchants downtown had no use for black customers. Even in 1970 vestiges of segregation remained in downtown Jackson. True, blacks no longer had to sit in the colored waiting room in the Greyhound bus terminal. But some lunch counters in town still refused to seat black customers. The counter stools had been removed to thwart integration. At the Mayflower Restaurant there were three bathrooms: one for men, one for women, and one still labelled “colored.”

To avoid such indignities and to buy the smaller items they needed, blacks patronized the stores on Lynch Street. At Dennis’s Shoe Store, for instance, you could buy a hat or have a new pair of heels tacked to your shoes while you waited in stocking feet. In the Magnolia Food Store you could buy a pack of cigarettes so you could sit and smoke and while away some porch time. Over at Johnson’s Barber Shop you could get a haircut and a good scalp massage, and leave feeling fresh and smelling fine. If they had the money, old folks who needed pills could pick them up at M-L-S Drugs, and anyone wanting to see a friend across town could get a ride up at the Deluxe Cab Company.

Lynch Street also had its own doctor and dentist offices, its own bank, an insurance company, a dry cleaner, and several gas stations, beauty parlors, corner stores, and bars. But the bars were what made Lynch Street an attraction. Some were for Jackson State students who went to dance and drink wine—dark, noisy, comfortable joints like the College Inn, the Tiger Lounge, the Psychedelic Shack, and the Doll’s House, where on weekends the cigarette smoke dimmed the lights and jukeboxes sent the hip-swivelling, mellow-angry soul music of James Brown and Aretha Franklin rolling out to the street.

Older Lynch Street residents resented them, but there was nothing they could do about the black youths on the corners in front of the joints. They were the “cornerboys,” nonstudents who either had dropped out of high school or never had gone on to college. They spent most of their time on the street and had names like Junebug, Tiny, Smiley, and Fats. Some had jobs. Some didn’t. To kill time, they often went over to Cooper’s to shoot pool, or squatted in the shadows behind a bar to roll dice. But mostly they stood on their corners, because that was cool.

“Those particular guys at that time—they would walk down the street and just break antennas off cars at night, or cut tires,” N. Alfred Handy, a black photographer on Lynch Street, recalls. “In other words, they wanted to rule and control the neighborhood. And when people resisted them, they had something against you. I remember once, I had purchased a new car and parked it in front of my place. And when I looked out about two o’clock that afternoon, guys was laying all over the car. Without saying nothing, I walked out and got in the car to go to work. Later on I parked it on the other side of the street. One of them got so mad he went over there and got sat on it. But what happened about ten o’clock that night, a guy came to the house and said, ‘Man, police lookin’ for you.’ I said, ‘What?’ He said, ‘Well, some guys broke some windows out of your store.’ This will give you an idea of the type guys that they were. They didn’t have jobs—maybe some of them—I’m not sure. But I know several couldn’t have jobs, because when you got here in the morning they were on the corner, and when you got here late at night they were on the corner.”

Jackson State students feared the cornerboys because many carried knives or guns. Some used the weapons to persuade male students to part with their wallets or their ladyfriends. For that reason, most students traveled in groups on Lynch Street, but brawls between the two factions were common. The cornerboys resented the students for taking on airs and for having one toe in the middle class. The students feared the cornerboys, who were often stronger, older, and armed. Yet now and then a few members of the college football team would make a special visit to a bar to kick ass and even the score.

But Lynch Street was not just a place to brawl or barhop. It was part of the Jackson State College community. Both the college and the black neighborhood had sprung from the same pastureland at the turn of the century. In those days, the whites didn’t cotton to the idea of coloreds learning to read and becoming schoolteachers. That is why Jackson College—as it was then called—was built on a rise a mile west of downtown. Originally, the campus had been closer to downtown on State Street. But in the late 1800s whites began building plantation-style mansions nearby. They resented the black students who rode mules and carried greasy lunch bags right past their new, white-columned palaces. And they didn’t like it when the blacks mingled with the white boys from the school nearby that Major Reuben Millsaps had started. So the black college was forced to pull up stakes and head for the farmland just west of downtown. The college quickly sold some of that land as building lots to black families, and by the early 1900s, the campus was surrounded and protected by black neighbors.

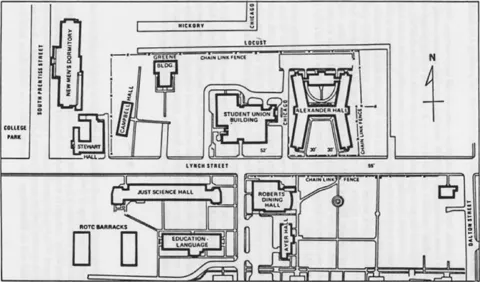

Over the years, Jackson State students came to call their campus “the yard.” But it was not beautiful. By 1970 Jackson State had become a state-supported college, and like most at the time, it spawned a hodgepodge of new buildings for the growing number of postwar baby-boom children in college. For example, looming above the four-lane traffic on the north side of Lynch Street were two new high-rise dormitories of red brick and green metal panels. One was Alexander Hall, a huge H-shaped dorm for women. In the commons park across the street was the library, another building of red brick and green panels. But nearby were Ayer Hall dormitory for women and Roberts Dining Hall, both of which were older, smaller, and painted white. On the lawn a block west was a pair of old white wooden barracks once used to house college athletes. Now they were used as offices by the ROTC staff.

Though there were no ivy walls at Jackson State, most students were proud of their school, which they saw as a black refuge from white Mississippi. It was a place where you could have a quiet, private talk with your girlfriend on a park bench under the oak trees. Or if she was across the street in her room in Alexander Hall, you could yell up to her and maybe she would come to the window and talk awhile.

To both the students and cornerboys, Lynch Street was their turf. Still, whites shuttled through each day and night, so conflict was inevitable. The crux of the problem was that nearly 60 percent of Jackson’s population demanded the other 40 percent remain separate and unequal. Though segregation was no longer the law of the South, most whites in Jackson remained ardent segregationists. To them, Lynch Street meant nigger street.

• •

One of the first racial confrontations in the Lynch Street neighborhood took place in the spring of 1961.

It had been more than a year since the historic day of January 31, 1960, when four black students in Greensboro, North Carolina had taken seats at a segregated Woolworth’s lunch counter. That move had inspired a wave of student sit-ins that had integrated public facilities in more than a hundred cities. But not in Mississippi. No one had dared a sit-in there until the drizzly, overcast morning of March 27, 1961. That day five young men and four women at Tougaloo College dressed in their Sunday best and left for the eight-mile drive south to downtown Jackson. Tougaloo was a private black college built on an antebellum cotton plantation just north of the Jackson city line. The students there resented the fact that the Jackson Municipal Library was for whites only.

Map of the Jackson State Campus. (Copy: President’s Commission on Campus Unrest)

Arriving in Jackson, the nine Tougaloo students broke the law by taking seats in the city library on State Street. Police in black jackets and white steel helmets threatened to arrest the students unless they left.

“Who is the leader, please?” asked Assistant Police Chief M. B. Pierce.

“Sir?” a female student replied.

“Who is the leader, please?” Pierce repeated.

“Leader of what, sir? There’s no leader.”

“You will all have to leave,” he ordered them. “The colored library is on Mill Street.”

When no one moved, Pierce arrested the nine students, hustled them off to the city jail and charged them with disturbing the peace. Finally, the sit-in had come to Mississippi.

On the Jackson State campus about a mile west of the city jail, a crowd of students gathered to protest the arrests. Marching around the aqua reflecting pools in front of the campus library, they chanted: “We want freedom! We want freedom!” One of these students was James Meredith, the Korean War veteran who would soon leave Jackson State to desegregate the University of Mississippi—an act that would result in a bloody clash between federal troops and white Mississippi. But at Jackson State that day, Meredith and his friends had planned their protests carefully to avoid violence.

“When President Jacob Reddix came onto the campus near the library, our group was loose,” Meredith remembers. “They were marching around the reflecting pools at first, but when he approached, they were tightening up into a small circle, everybody holding hands and one student praying. . . . So everybody kept listening to his prayer, and nobody paid any attention that the president was around, as far as responding to whatever he was saying. The president was visibly upset by the fact that no one paid him any attention, and he did what was part of the plan. He did some foolish things.”

Reddix, conservative black patriarch of Jackson State, threatened to expel the students. Witnesses said he even shoved some in the crowd. The students dispersed quickly, and soon Chief Pierce and the city police were on campus with guns, clubs, tear gas, and two attack dogs. Though the protesters had gone and the demonstration was over, the lawmen cruised up and down Lynch Street that night. But the next morning, the marching, praying, and chanting began again.

“The girls were instructed to wear the school colors and all the boys were to wear black and white,” James Meredith adds. “So they all were told not to go to school, but to come to the dining hall and meet at the earliest time it opened. Everybody was there and dressed out. This was early—I mean, like 6:00 in the morning—6:30 at the latest. That’s when it all began. The demonstrations went on all day, one way or another. We shifted students from one place to another to avoid counter-influences.”

But after the protest on campus had finished, one group of about sixty students walked single file down Lynch Street, heading east toward the city jail where the Tougaloo youths were held. The protesters carried American flags as they turned north off Lynch Street to avoid the city police. But just a couple of blocks from the campus, they looked down the road and saw lines of city police, county patrolmen, and deputy sheriffs waiting behind barricades. The officers warned the students to turn around. When they did not, the lawmen rushed the youths, swinging clubs, firing tear gas, and unleashing their snarling dogs upon the crowd. Choking and crying...