![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Melodic Tradition of Ireland

Any account of a living tradition is necessarily an account of musical change. When Cecil Sharp described folk culture as a synthesis of the forces of continuity, variation, and selection (1907, 21), he was emphasizing the fact that performers of folk music are most highly respected when they introduce changes or variations into their music, provided that they ultimately satisfy the demands of the forces of continuity (of general style) and selection (by the musical community).

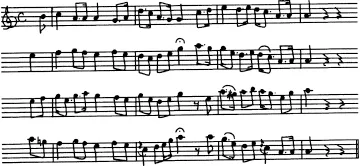

These congenial changes do not always lend themselves to a diachronic, historical analysis. Consider, for example, the tune “Molly Macalpin,” noted down by the Irish musician Edward Bunting near the end of the eighteenth century (ex. 1).

Flood has suggested that the song dated from around 1601, when five members of the MacAlpin family were outlawed “and, as was customary by the Irish bards, a lament was composed for one of the ladies of this family, ever since known as ‘Molly MacAlpin’” (1913, 183). This early date does not quite tally with the popular belief presented to Bunting by his informants, that the piece was composed by a harper named William (a.k.a. Laurence) Connellan, born around 1645 (O’Sullivan 1958, 1:18). Bunting also mentioned that a later Irish harper, Turlough O Carolan (1670–1738), was “heard to say that he would rather have been the author of ‘Molly MacAlpin’ than of any melody he himself had ever composed,” to which O’Sullivan added the tantalizing remark that Carolan “may have modified [the tune] to some extent” (1958, 2:113). Whatever its provenance, the air was common enough among Irish folk musicians in the nineteenth century to have caught the ear of P. W. Joyce, who published it in 1909 (ex. 2).

Ex. 1. “Molly Macalpin” (Bunting, 1810, 11); transposed up a fourth

Ex. 2. “Moll Halfpenny” (Joyce 1909, 68–69)

We may well say that some changes took place between Bunting’s notation of the tune c. 1800 and Joyce’s c. 1900. Note that even the title has “evolved,” the old Irish name “MacAlpin” giving way to the English monetary unit, “halfpenny.” A modern version, transcribed from a recent recording, shows even more change (ex. 3).

Apparently, our seventeenth-century lament has become a vigorous hornpipe, and Molly MacAlpin has become “Paul Halfpenny.” Surely this must be a clear documentation of the diachronic process of musical change in an oral tradition.

Ex. 3. “Paul Halfpenny” (Casey R1979, B1)

Or is it? Have we really demonstrated a historical chain of events? We may imagine that the tune, rescued from oblivion by Bunting and “immortalized” as the parlor song “Remember the Glories of Brian the Brave” (new text by Thomas Moore), was picked up by folk musicians and transformed gradually into the hornpipe heard today; but the opposite is just as possible! After all, Bunting and Moore (as we will see later) held no little contempt for the “ignorant” folk musicians of their time, preferring the comparatively elite class of harpers and their repertory. A folk dance tune with the same contour as “Molly MacAlpin” could have escaped their notice. In addition, Bunting conceded that even the great Carolan seems sometimes to have “composed” new pieces by slightly reworking folk tunes.1 In light of this fact, and with no proof to the contrary, we may as well imagine that this tune has been a hornpipe for centuries, one which was perhaps “borrowed” for Connellan’s lament, but which—being but a vulgar dance tune—was missed or ignored by collectors until the nineteenth century.

In other words, diachronic analysis has not provided us with any concrete information about the process of melodic change. Speculation may be entertaining, but it will not bring us any closer to an understanding of the ways in which traditional musicians work with their materials. For this kind of understanding we must turn to a more synchronic analysis.

A synchronic analysis of melodic change does not deny the historical element; it just shifts the focus of our study away from the linear aspect of change, toward an investigation of the conditions in which change takes place. This shift of focus was articulated well by the Irish piper and sean-nós singer, Tomás Ó Canainn:

A performance of traditional music is a thing of the moment—a few short minutes filled with music that is the result of many hours of practice, years of listening and perhaps generations of involvement in the tradition. In the past such a performance left no permanent record save in the mind of the listener. Does this mean that it is gone forever, without trace? In the traditional music context such a thing is unthinkable. (Ó Canainn 1978b, 40)

Echoing the words of T. S. Eliot about tradition in poetry (1932, 4–5), Ó Canainn described the synchronic sense of tradition which the Irish traditional musician feels:

This sense of the timeless and the temporal together is very much a part of his make-up. He sees his performance in relation to that of other musicians who have gone before him, as well as in the context of the living tradition, and he often refers to this aspect of his music.

His place is among the past generations of musicians as well as among his contemporaries. His performance only has its full meaning when measured against theirs, not necessarily in a spirit of competition: their contribution, though past, is to some extent affected by his. With every performance he is, as it were, shifting the centre of gravity of the tradition towards himself, however minutely, and is reestablishing the hierarchy of performers past and present. (Ó Canainn 1978b, 41)

In the following chapters I shall present several synchronic studies which may help to illuminate the workings of Sharp’s trinity of forces—continuity, variation, and selection—and the ways they intertwine to shape that particular context, the melodic tradition of Ireland. In preparation for these studies, readers who are unfamiliar with Irish folk music may wish for some basic information about traditional Irish culture, and the scales, forms, and instruments constituting the background against which the studies will be projected.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Traditional Irish music has been evolving over at least the last two centuries into the forms in which it is heard today. Most traditional musicians feel that their music comes from times even more distant. Although no evidence refutes this idea, there is little to support it concretely, as the music of Irish peasants was not considered a matter of scholarly interest until the nineteenth century. Before that time, references to indigenous Irish music were fragmentary, shedding little light on specific musical practices. However, these scattered and tantalizing references have become part of the mythos of the music, and as such they have a place in a discussion of the historical background perceived by modern traditional musicians.

This is not the place to chronicle the ebb and flow of political fortunes in Ireland, for that story is intricate and too often oversimplified. Mythological and historical considerations are mentioned here only in relation to those cultural consequences which affected the music and the way it is perceived today.

The earliest human artifacts unearthed in Ireland show that Neolithic people were there around 6000 B.C. Bronze Age sites show great stoneworks—dolmens, raths, and tombs—but little is known of indigenous culture before the coming of the Gaels around the middle of the fourth century B.C. Popular imagination, mixed perhaps with a vestige of truth, has peopled pre-Gaelic Ireland with four waves of inhabitants. First came the Fomorians, sinister giants who embodied Evil. They were conquered by the Firbolgs, who were small and shrewd, overcoming their giant foes by superior cunning. The Firbolgs were eventually vanquished by the Danaans, often seen as the embodiment of Good. The Danaans were able to manipulate nature to some extent, due to their close harmony with natural forces; but eventually they fell before the invading Milesians. The Danaans then transformed themselves into the invisible “little people” known as “leprechauns,” “sí,” or “fairies,” and inhabited the old stoneworks and various other parts of the Irish countryside. The Milesians were in turn ousted by the Gaels.

The Gaels revered the memory of the Danaans—perhaps because of their common foes, but for cultural reasons as well. “The Gaels attributed their own love of poetry and desire for knowledge to the Danaans. Lugh himself, the sun god, and Eriu, earth goddess of Ireland, were said to have been Danaan in origin.… Even the Lia Fall, the sacred stone of Tara, was said to have derived its magical powers from the Danaans” (Costigan 1969, 12). The Danaans were also admired for their music, and today the music of the fairies is often said to be the sweetest music ever heard. Many folktales attest to the supernatural powers of fairy music, and several tunes in the modern oral tradition are said to have been composed by the fairies.

Music was very important to the Gaels, too. Flood (1913, 23) collated a list of instrument types used in Gaelic courts: harps (cruit and cláirseach); zithers (psalterium, nabla, tiompán, kinnor, trigonon, and ochttedach); fiddles (fidil); flutes (feadán); shawms (buinne and guthbuinne); bagpipes (cuisle and píopaí); horns (bennbuabhal and corn); trumpets (stoc and sturgan); and percussion (craebh ciúil, crann ciúil, and cnámha).

We have no concrete knowledge of the tunes and playing styles of the early Gaelic court musicians, but a suggestion of a developed musical system is found in their variously interpreted musical categories, given by Breathnach (1971, 2–4) as goltraí (music for sorrow), geantraí (music for happiness), and suantraí (music for sleep). Citing eighteenth- and nineteenth-century sources, Flood gave the terms as goltraighe (music for valor), geantraighe (music for love), and suantraighe (music for rest), translating traighe as “a mode or measure,” and designating each of the three categories as belonging to one of the three Greek musical modes, Dorian, Phrygian, and Lydian (1913, 35). At least one example of “music of valor” may have survived from the Gaelic courts: “Brian Boru’s March”2 is believed by some to have come from the period of that monarch, perhaps having filled the air on Good Friday in 1014, when his forces won the decisive victory over the Viking invaders at Clontarf.

The Anglo-Norman invasion of 1170 was the first wave of the English conquest of Ireland. With the establishment of the Pale, a safe zone for Englishmen on Irish soil, the partitioning of the island began. “Beyond the Pale,” as the expression now goes, Gaelic culture was at first comparatively intact.

Giraldus Cambrensis, a dignitary of the Welsh church, visited Dublin in 1185 in the train of the English Prince John. Justifying the conquest, Giraldus wrote later that the Gaels were “the foulest, the most sunk in vice, the most uninstructed in the rudiments of faith of all nations upon the earth” (quoted in Costigan 1969, 39). Given this viewpoint, it is all the more striking that Giraldus heaped praise upon the Gaelic harpers:

They are incomparably more skillful than any other nation I have ever seen. For their manner of playing on these instruments, unlike that of the Britons to which I am accustomed, is not slow and harsh, but lively and rapid, while the melody is both sweet and pleasing. It is astonishing that in such a complex and rapid movement of the fingers the musical proportions can be preserved, and that throughout the difficult modulations on their various instruments the harmony, notwithstanding shakes and slurs, and variously intertwined organizing, is completely observed.… They delight with so much delicacy, and soothe so softly, that the excellence of their art seems to lie in concealing it.” (Quoted in Flood 1913, 61)

Many of the English colonists were attracted to Irish music and other aspects of indigenous culture. Itinerant Irish musicians were as welcome in homes of many of the foreigners as they were outside the Pale. Suspicions were aroused, perhaps rightly so: it seemed that the colonists were “going native” to an alarming extent, and it also appeared that traveling musicians were in a position to carry sensitive information to elements hostile to the British. A series of penal laws were passed, aimed largely at outlawing Gaelic culture. An ordinance in 1360 made it unlawful for an Englishman to speak in the Irish language, and the Statute of Kilkenny (1367) forbade contact between the English colonists and Irish musicians and poets. Perhaps this act was not much enforced at first, for similar acts were again decreed in 1481 and 1524.

The penal laws became broader under Queen Elizabeth, and Irish poets and musicians were outlawed by six statutes between 1563 and 1603. This last proclamation was accompanied by an order from Queen Elizabeth to “hang the harpers wherever found and destroy their instruments” (quoted in Flood 1913, 186). Under such severe persecution the courtly tradition of the Irish harp was eventually eradicated. A vestige of it held on through the eighteenth century, which saw the career of the last great harper-composer, Turlough O Carolan; but with the deaths of Carolan and his few successors, the story of indigenous Irish court music came to a close.

We know nothing of the early forms of Irish folk music, except that learned contemporaries apparently considered it vulgar and unworthy of description. The penal laws were unsuccessful in wiping it out; unlike the more rarefied court music, Gaelic folk music proved both adaptable and acquisitive. Various musical influences, often diffi...

-plgo-compressed.webp)