![]()

1 | Introduction

Britain, Germany, and the Middle East, 1871–1904 |

“To defeat the enemy,” a key British official concluded during 1915, in the midst of World War I, “the destruction of the Ottoman Empire would be a decisive step.”1 How could Britain best achieve this radical break, discussed even before the world war, with its longtime foreign policy that had aimed at preserving the Turkish state? What would replace Turkey as the bulwark safeguarding Britain’s shortest route to India, the heart of Britain’s vast global empire?

According to the official, Britain should “back Arabic speaking peoples against the Turkish Government,” destroy the Ottoman Empire, and create from its ruins an independent confederation of pro-British Arab states.2 A few months later in 1916, with Britain’s encouragement and military assistance, the Sharif of Mecca, Husayn ibn Ali, the guardian of the holy places of Islam, led a revolt of Arabs in the Hijaz, a region of western Arabia, against their Ottoman ruler, the sultan-caliph.

The British-sponsored Arab revolt, assisting as it did the triumph of Britain and its allies in the war in the Middle Eastern theater, had a vital impact on the future of that region and of the Islamic world. As this study illustrates, important roots of the revolt in 1916, like those of other wartime policies pursued by Britain in the Middle East, were deeply embedded in Britain’s prewar antagonism toward, and rivalry with, Imperial Germany. The policy of waging “war by revolution” in the Middle East, pursued by both Germany and Britain between 1914 and 1918, had its origins long before the world war, in the arrival there of the first imperial powers—Britain and France, and later Germany.

The British Empire, the Sultan-Caliph, and Pan-Islamism

By 1907 the largest European empire, that of Britain’s, included India, southern Persia, the principal shaykhdoms of the Persian Gulf, Aden, Egypt, and a portion of the sultanate of Zanzibar along the East African coast. The empire numbered ninety-six million Muslim subjects, almost one-third of the world’s Muslim population. In contrast, the number of Muslims under French rule in Africa and Asia totaled nineteen million, roughly as many as lived under Russian rule in Central Asia.3

London exercised much of its vast influence in the Middle East and southern Asia through its colonial, but powerful and often independent, Government of India. Not only did the Raj win or force promises from local Arab shaykhdoms (which included Kuwait and Muhammarah) in the neighboring Persian Gulf to keep foreigners out, but it handled Britain’s relations with Aden, Afghanistan, and the Ottoman provinces of southern Mesopotamia.4

Britain also attempted, as part of its Middle East policy, to preserve the most powerful, but continuously declining, Muslim state, the Ottoman Empire, which lay on the route from Europe to India. Since, particularly, 1830 Britain had engaged in what Englishmen called “the Great Game,” protecting India from Russian attack; it was for that purpose that the British extended their influence into Turkey, and into other Islamic states, including Persia and Afghanistan, as well.5

The Ottoman Empire, despite the effective loss of its rule in Egypt to Britain in 1882, of Tunis to France in 1881, of Libya to Italy in 1911–1912, and of the Muslim khanates of Turkestan to Russia, remained the only significant focus of Muslim power in the world. The despotic sultan-caliph, Abd ul-Hamid, in part to offset the loss of Ottoman territories to the West and Russia, attempted not only to centralize his power in the remainder of the empire but also, in the process, to establish the doctrine of pan-Islamism. According to that ideology the Turks proclaimed the sultan the true and rightful caliph who, having inherited his office from the last Arab caliph in 1517, held a religious authority, distinct from political authority, over all the world’s Muslims. Furthermore, pan-Islamism called on all Muslims to defend the Turkish empire and caliphate against the infidel, even by waging holy war.6

The extent to which Muslims accepted these doctrines is problematic; some found it convenient to embrace them, while others rejected them as false arguments. By the end of the nineteenth century a handful of Arab writers who urged a reform and reawakening of Islam viewed the Turks as degenerate Muslims who, unlike the Arabs, had not received the original revelation and whose rule should be replaced by an Arab caliphate. Nevertheless, most Arabs and other Muslims looked to the Ottoman sultan as the most powerful independent Muslim ruler, a pillar of support in a world increasingly hostile to Islam—a world in which the great majority of Muslims lived under alien rule.7

In the view of Englishmen and other Europeans, pan-Islamism posed a serious menace. They believed only too easily the idea, medieval and Social Darwinian in origin, that Muslims were essentially inferior and fanatical savages, prone to violence in response to religious appeals. Furthermore, Europeans viewed the sultan as the murderer of Christians, particularly because of the Ottoman massacres during the 1890s of Armenians in the eastern Anatolian provinces of the empire.8 Accordingly, the Europeans feared that if they pressed the sultan too hard they might be confronted with pan-Islamic agitation, and even revolt, in their Muslim colonies. This especially haunted Britain after the Great Rebellion of 1857 in India, although that revolt had nothing to do with pan-Islamism. Twenty years later, however, during the Russo-Turkish War, the Muslims of India for the first time demonstrated their sympathy for the Turks on a significant scale.9

German Interest in the Muslim World

During the 1880s and 1890s a new factor appeared in the Middle East, one that the British believed threatened their supreme position in the region: the growing prestige at Constantinople of Imperial Germany. Among the European powers the German Empire arrived late as a global imperialist competitor. Because this was particularly true in the Middle East and Africa, Germany appeared free from the taint—as the Turks viewed it—of snatching land from the Ottomans. Berlin, in sharp contrast to Britain, ruled only a few overseas lands, which contained a small number of Muslim subjects—in 1914, roughly 2,600,000, scattered through East and South-West Africa and the Kamerun.10

Only during his last years had the “iron chancellor,” Otto Prince von Bismarck, involved Germany in the affairs of the Middle East. Concerned mainly with the security of the new German Empire in central Europe, he had encouraged the diversion to Europe’s periphery—the Middle East and Africa—of the attention of Europe’s other Great Powers, including Britain.11 But by the end of the 1880s, Bismarck’s entry into the race for overseas colonies led him to side with France against Britain, encouraging the latter to make concessions to Germany in South-West Africa, the Kamerun, and Togoland, and in such islands as Zanzibar, New Guinea, and Samoa.12

Bismarck’s policy also included preservation of what remained of the Ottoman Empire, despite its serious internal problems and losses of land to Britain, France, and Russia. German interest in Turkey long predated the Bismarckian era;13 nonetheless under his leadership Germany saw the Turkish state as a bulwark against Russian expansion into the Middle East and Balkans. Consequently, Bismarck consented in 1882 to Turkish requests for a military mission to Constantinople to assist in reforming the sultan’s army. The dispatch of the officers soon began a steady German pénétration pacifique of the Ottoman Empire. This included shipments of armaments to Turkey and concessions for construction of the Anatolian railroad.14 Despite his support for the Ottoman Empire, Bismarck exerted himself for none of the non-Turkish peoples, including the Arabs, who lived under Ottoman rule. Moreover, he remained silent about the severe mistreatment by the Sublime Porte (the Turkish government, so named for the gate of the sultan’s palace) of the Christian peoples in its provinces of the Balkans and eastern Anatolia. German officials were as little concerned for such peoples, or the Arabs, as they were for their own national minorities at home.15 Nevertheless, the German leaders viewed them and that part of the world as having increasing importance for Germany, as illustrated by the founding in 1887 in Berlin of the Seminar for Oriental Languages.16

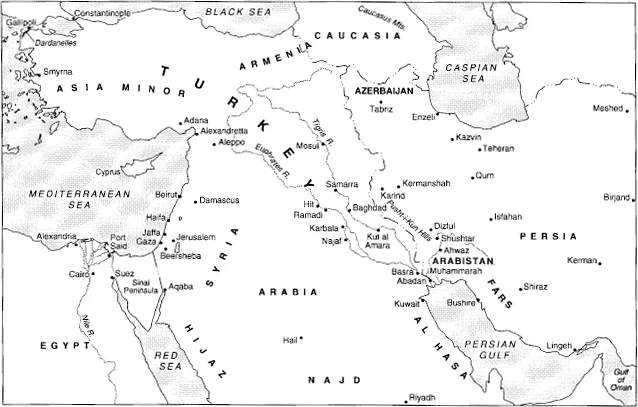

The Middle East in World War I.

In the Bismarckian view, the only possible value of foreign peoples, particularly minorities, was in producing problems for a military or political enemy of Germany. For instance, as early as 1866, during the Austro-Prussian War, the Prussian government established contacts with nationality groups in Austria, including the Hungarians and Slavs, with the idea of persuading them to revolt against the government in Vienna. After the formation of the German Empire, its army high command envisioned striking Russia, as one officer said, by fomenting revolution or insurgency among the non-Russian minorities along Russia’s “vulnerable borders.”17

The idea of inciting revolt among the minorities of a foreign enemy of Germany did not end with Bismarck’s dismissal in 1890. Thereafter the German emperor, the young and belligerent Wilhelm II, and others in his government, expanded the concept. While intensifying Germany’s role in Turkey, they discussed pan-Islamism and its potential for promoting insurgency in the vast colonial holdings around the world of competing imperialist nations.18

In part this idea reflected the kaiser’s “new course” in German foreign policy, officially proclaimed during 1896 and 1897 by Wilhelm and his foreign secretary, Bernhard von Bülow: pursuing expanded German influence overseas—in fact, global power.19 The resulting Weltpolitik, based on the construction of a powerful new battle fleet and on Berlin’s eagerness to push its advantage at every international crisis point, produced sharp disagreements with other nations, particularly Britain, France, and the United States, over colonial territories in the Far East, Latin America, and Africa.20

Moreover, both Britain and Russia felt endangered by the steadily expanding German economic and military influence in the Ottoman Empire. Although London, as well as some historians much later, eventually believed that Germany intended to turn Turkey into a satellite or colony of the Reich, German policy toward Constantinople seemed much less defined and consistent at the time. Actually, Berlin’s approach to the Ottoman Empire was dictated to a considerable extent by the kaiser’s personal and quixotic views on the potential usefulness of Turkey and Islam against Britain, identified by Wilhelm II and many other Germans as their nation’s archenemy.21

Britain’s unhappiness with Germany in Turkey first emerged in the mid-1890s. The British disliked Berlin’s refusal to oppose the Porte’s massacre of the Armenians, as well as German support of the Ottomans in the Turkish-Greek war over Crete in 1897. While Turkey and Greece fought, Muslims in India conspicuously displayed their sympathy for the Turks.22

Furthermore, throughout the 1890s the amir (a Muslim ruler) of Afghanistan spread anti-British propaganda among the predominantly Muslim tribes along the northwest frontier of India. He opposed any extension of British influence across the border into his country and incited the tribes on both sides of the frontier to rise in revolt. Also from 1898 to 1902 the amir employed a German cannon maker of the Krupp company at an armaments factory in Kabul. The problems with Afghanistan awakened in Britain and the Government of India renewed anxiety about pan-Islamism (although in fact such actions had less to do with fanatical pan-Islamism than with nationalism and a wish for independence on the part of some Indian Muslims).23 Still other British fears resulted from the long effort in the Sudan by Anglo-Egyptian forces, which finally succeeded in 1898 in defeating the khalifa, the successor to the mahdi (messenger of God), who had ruled the country since 1883 by playing on the Muslim fanaticism of the tribes.24

Other factors added to Britain’s concern about India, pan-Islamism, and the growing German presence in the Middle East. These included Britain’s clashes with Russia in central Asia and the fact that the British navy, which was badly overtaxed by defending Britain’s far-flung empire, could no longer protect the Black Sea straits from a Russian attack. By the end of the 1890s Britain’s conservative government under Lord Salisbury even began lessening its role in Constantinople in favor of building up British strength in Egypt.25

The Kaiser and the “Red Sultan”

Especially disturbing, however, to Britain—as well as to France and Russia—was the involvement of Germany in the politics of pan-Islamism. During October and November 1898 Wilhelm II journeyed for the second time in nine years to Turkey, where he embraced publicly the world of Islam and its people. The kaiser, according to Bülow, who accompanied the emperor to Turkey, held an “excessive enthusiasm and exaggerated zeal for everything Turkish and Mohammedan.”26

The reasons for his fascination with the Orient (a word used by nineteenth-century Europeans to describe the “Eastern” or Middle Eastern world) and Islam were various. On the one hand, Wilhelm’s views re...