- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

An examination of the important role of Ohio in U.S. presidential history

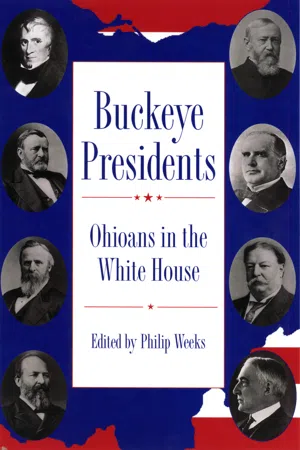

Only two states can claim the title "the Mother of U.S. Presidents"—Ohio and Virginia. Fifteen presidents have hailed from either Ohio or Virginia, though one of those men, William Henry Harrison, is attributed to both states. The other seven men from Ohio who have piloted the United States from the White House are Ulysses S. Grant, Rutherford B. Hayes, James A. Garfield, Benjamin Harrison, William McKinley, William Howard Taft, and Warren G. Harding.

Drawing on recent scholarship, the essays place each president squarely in the context of his time.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Buckeye Presidents by Philip Weeks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

The Early Republic

William Henry Harrison

Ninth President of the United States, 1841

It was cold on the morning of March 4, 1841, as participants assembled for the inaugural parade of president-elect William Henry Harrison. Though the Whig party of Baltimore had offered a carriage and a team of four matched horses for the occasion, the sixty-eight-year-old Harrison chose to ride a spirited white charger. Despite the chill, the general wore no overcoat and carried his hat so he could acknowledge the cheers of the spectators as he made his way along Pennsylvania Avenue toward the Capitol. To his right and left rode Maj. Henry Hurst and Col. Charles Stewart Todd, both of whom had served as his aides at the Battle of the Thames during the War of 1812. Behind them followed an escort of mounted assistant marshals. Then came Tippecanoe Clubs with banners and bands, some with log cabins on wheels, and many decorated with cider barrels and coonskins or other symbols of the frontier to honor this man from America’s first West. Representing industry was a large platform drawn by six horses that bore a working power loom. From Georgetown, next door to Washington, D.C., marched the faculty and student body from the Jesuit college there.

At the Capitol, where an estimated 50,000 spectators had gathered, a fortunate thousand were admitted to the Senate Chamber gallery to watch newly elected senators and the vice-president-elect, John Tyler, take their oaths.

Then came the grand moment. At thirty minutes after noon, the dignitaries processed from the Senate Chamber, through the Capitol building, and out to a platform constructed at the east front of the building. Harrison took his place next to Chief Justice of the United States Roger B. Taney, with other Supreme Court justices, senators, the corps of ambassadors, and ladies seated around them. When Harrison rose, the multitude cheered, then listened as he delivered his inaugural address over the next hour and a half, speaking into a cold northeast wind, still without benefit of overcoat, gloves, or hat, while his warmly dressed auditors huddled against the icy gusts. At the close of his speech, the chief justice administered the oath of office.

When the official festivities concluded, Harrison repaired to the White House to receive hundreds of well wishers, and that night, despite the length of the day, he attended a ball where many toasts were proposed for the success of the new Whig administration. Thus, says the chronicler Benjamin Perley Poore, the “Democrats surrendered the power which they had so despotically wielded for twelve years,” and the Whigs “took the reins of government.”

Exactly one month later, on April 4, 1841, Harrison became the first president to die in office.

William Henry Harrison began life as a child of privilege. The first Harrison arrived in Virginia about 1634, acquired land, and served in the House of Burgesses. William Henry’s father, Benjamin Harrison V, was a member of the First and Second Continental Congresses, signed the Declaration of Independence, served in the Virginia legislature, and in 1781 defeated Thomas Jefferson to become governor of Virginia.

William Henry, Benjamin’s third son, was born at the family estate at Berkeley, Virginia, on February 9, 1773. At fourteen, he was sent to Hampden-Sidney College, a small Presbyterian school in Hanover County, but, for reasons that are not clear, his stay there was brief. Historians have speculated that a “religious phrensy [sic]”—as Thomas Jefferson styled it—that swept the school so disturbed the staid Episcopalian Harrison that he was withdrawn. In 1790, Harrison, still but seventeen, was sent to study medicine with Dr. Andrew Leiper in Richmond, but there the impetuous youth joined an abolition society, which must have been a severe trial to his slave-owning father. The next year he was sent to Philadelphia, then the nation’s capital, to complete his medical studies at Pennsylvania University under the direction of the eminent Dr. Benjamin Rush. When he reached Philadelphia, however, he learned that his father had died. Harrison attended the medical school for a time, but when Virginia governor Richard Henry Lee was in the capital, Harrison asked him to help him secure a commission in the army. It was accomplished within twenty-four hours, and on August 16, 1791, Harrison was appointed an ensign in the First Regiment of Infantry, with orders to recruit soldiers and lead them to Fort Washington, on the Ohio frontier near Cincinnati.

Army service in the Northwest Territory, the vast area north of the Ohio River, was a formative experience for the young officer. Between 1785 and 1789, the Ohio tribes had signed land cession treaties with the United States, but Indians complained that their councils had not approved the agreements and resisted American encroachments. In September 1791, Arthur St. Clair, the governor of the Northwest Territory, led 1,400 men north from Fort Washington. Near the east bank of the Wabash River, a hundred miles north of Cincinnati, Indians, supported by the British, attacked St. Clair’s army at dawn on November 4, 1791. Six hundred of St. Clair’s men and fifty-six female camp followers were killed in the worst defeat ever suffered by an American army at the hands of Indians in a single battle. The survivors retreated in disarray through the wilderness. Harrison arrived at Fort Washington just as the remnants of St. Clair’s army reached the post. It was a sight that the young ensign never forgot.

Over the next few months, Harrison grew into a competent officer. At first his fellow soldiers scorned him because he had obtained his commission through political favoritism. According to his own account, he spent his time reading Cicero’s Orations, books on military tactics, and other worthy tomes. In 1792, Congress enlarged the army to 5,414 men, and President Washington appointed Revolutionary War hero “Mad Anthony” Wayne commander of U.S. forces in the West. Wayne made Harrison, newly promoted to lieutenant, one of his aides.

In August 1794, Wayne led 2,000 regulars and 1,500 Kentucky volunteers, under Maj. Gen. Charles Scott, against the Ohio Indians. Fought near a British fort by present-day Toledo, the Battle of Fallen Timbers raged for an hour, with Harrison in the thick of the action, before the beaten tribesmen ran for the protection of the British post, only to find its gates closed. For the next three days, U.S. forces burned and pillaged Indian towns and fields in the area. Then, following the Maumee River to its confluence with the St. Marys and St. Joseph Rivers in Indiana, they established Fort Wayne on the site of the Miami Indian town of Kekionga, before moving on to Greenville.

On August 3, 1795, ninety-two chiefs, representing twelve tribes, and twenty-seven whites, including Harrison and General Wayne, signed the Treaty of Greenville, in which the Indians ceded 25,000 square miles of land in northern and western Ohio in exchange for $20,000 in goods and a $9,500 annuity, or less than one-sixth of a cent per acre. Harrison would later apply Wayne’s questionable methods of dealing with Indians—the rituals of awarding medals to chiefs, ornate rhetoric, exchanges of wampum, smoking calumet pipes, and tippling alcohol—when concluding his own land cession treaties.

Harrison was assigned to a blockhouse at North Bend on the Ohio River, fourteen miles downriver from Cincinnati. North Bend was the home of Judge John Cleves Symmes, a prominent citizen and landowner, and Harrison soon developed a romance with the judge’s daughter, Anna. Symmes complained to a friend that, though Harrison came from a good background, “he has no profession but that of army.” A year later the judge still expressed reservations because his son-in-law could “neither bleed, plead, nor preach, and if he could plow I should be satisfied.” Despite the judge’s misgivings, William Henry and Anna enjoyed a loving relationship spanning forty-five years.

After his marriage, Harrison decided that the army offered few opportunities for an ambitious man. In 1798, he resigned his commission and won appointment as secretary of the Northwest Territory, maintaining the territory’s records—including laws, land claim decisions, an account of the governor’s actions for Congress, and returns of land surveys. He was also authorized to serve as acting governor when necessary. That year a census revealed an increase in population that, by the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, allowed the territory to advance to second grade. That meant it could establish an elected general assembly that could select a nonvoting delegate to Congress. Harrison ran for the position and was elected over Arthur St. Clair Jr., the son of the territorial governor, by a close vote of eleven to ten.

Harrison’s most significant accomplishment as a member of the 6th Congress involved federal land policy. During the Confederation period, Congress had established the basic western land policy of the United States when, in 1784, 1785, and 1787, it passed land ordinances establishing policies for the orderly survey, sale, settlement, and government of the Northwest Territory. At this point, the only offices for public land sales were at Pittsburgh and Cincinnati. The laws favored wealthy individuals who could buy large amounts of land for speculation or break it into smaller lots to sell at higher prices.

The people of the Northwest wanted land available in smaller tracts, and Harrison represented their interests well. At his suggestion Congress appointed a committee to reexamine the land law and named Harrison to chair it. In the Land Act of 1800, Congress adopted Harrison’s recommendations to reduce the minimum sale from 640 acres to 320 acres and to open additional land offices in Ohio at Chillicothe, Marietta, and Steubenville. The price remained two dollars per acre, but the time for payment was increased from one year to four. The measure had an immediate impact on flagging land sales. By the end of the year nearly 400,000 acres were sold, and another 340,000 were sold in 1802. Historian John D. Barnhart in Valley of Democracy credits the Land Act for the large migration to Ohio, which would lead to statehood in 1803.

Harrison also proposed the partition of the Northwest Territory. President John Adams, on May 13, 1800, approved a bill dividing the Ohio Territory from the remainder, called the Indiana Territory, along a line due north from the confluence of the Great Miami and Ohio Rivers. One week later Adams appointed Harrison governor of the Indiana Territory, at that time a huge expanse that included not only the present state of Indiana but also Illinois, Wisconsin, and portions of Michigan and Minnesota (and for a brief time after the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, the area as far west as the Rocky Mountains).

Harrison also represented the private interests of his father-in-law, who owned considerable land in the Northwest Territory. The Land Act of 1785 required that one section of every township be set aside for supporting public schools, but John Cleves Symmes had never fulfilled that obligation. The territorial legislature had instructed Harrison to initiate legal proceedings against his father-in-law if necessary, but Harrison made no efforts to do so.

Harrison arrived at the Indiana territorial capital of Vincennes in January 1801 and settled into the life of a frontier gentleman. He purchased several hundred acres of land and built an elegant brick house to accommodate his busy professional and social life and to provide room for his growing family (the Harrisons’ fifth child, John Scott, was born in October 1804). The house, which he named Grouseland, still stands today.

Territorial governors exercised considerable power. At first Harrison, along with three appointed judges, made all laws by decree. After the territory advanced to second grade in 1805, the elected territorial legislature enacted laws, but Harrison retained an absolute veto and the power to appoint almost all territorial officials; and though President Jefferson had the authority to name the territory’s legislative council, in fact he left the matter to Governor Harrison. For Harrison and his supporters, as Andrew R. L. Cayton has shown in Frontier Indiana, politics was a “hierarchical business” that “operated essentially as a personal faction, acquiring and exercising power through a vertical face-to-face system of patronage.”

Harrison made enemies because of his exercise of power. In 1805 an anonymous critic—whom most historians identify as Isaac Darneille—published several letters under the pseudonym Philo Decius, denouncing the governor as “a whimsical and capricious executive” who appointed his cronies to office and ruled against the land claims of those who dared to oppose him. Another adversary was John Badollet, the register of the land office in Indiana, who protested to Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin that Harrison had cheated settlers and Indians out of their land, tried to prevent the election of Jonathan Jennings as territorial delegate to Congress, and circulated petitions for his reappointment as governor at “abodes of intemperance” and among crowds at horse races. Harrison, he said, was a “moral cameleon [sic]” who could assume “a variety of appearances to answer his purposes, vulgar with the lowest order of mankind, polite … fascinating with the more refined.”

Jennings proved Harrison’s most formidable opponent. A Pennsylvanian who arrived in Indiana in 1806, Jennings served as the territory’s delegate in Congress from 1809 until 1816, when Indiana attained statehood. In 1810 he introduced a resolution in Congress—which did not pass—that would prohibit the selection of the governor’s appointees to the territorial House or the legislative council. The next year Jennings proposed that Congress allow sheriffs in the territory to be elected instead of appointed by the governor. Throughout his political career, which included service as the new state’s first governor from 1816 to 1822 and another stint in the U.S. House from 1822 to 1831, Jennings remained an implacable foe of Harrison, whom he denounced as a member of the Virginia aristocracy.

There were also allegations that Harrison used his office to speculate in public lands, that he bribed others not to bid on public lands and accepted bribes for not bidding on public lands himself. In fact, Harrison, like many other officials, speculated in land despite his official position. There was no rule that prevented such activity, but Secretary Albert Gallatin considered it “extremely improper” and eventually issued an instruction forbidding land superintendents from being involved in speculations.

The question of slavery in the Northwest Territory was another controversial issue. Article VI of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 had prohibited the introduction of slavery into the territory, but Harrison and others—particularly Virginians raised on plantations—wanted to suspend or repeal Article VI. They argued that the introduction of slavery would encourage the territory’s population growth and economic development. In December 1802, a convention at Vincennes, called and presided over by Harrison, petitioned Congress to suspend Article VI for ten years. When Congress was not forthcoming, the governor and the territorial judges promulgated a law that reduced black servants brought into the territory to a condition little short of slavery. After Indiana advanced to second grade, the territorial legislature, with Harrison’s support, again petitioned for the suspension of Article VI and passed an act declaring that black servants could be brought into the territory under “voluntary” agreements.

Harrison’s efforts to extend slavery into the territory aroused strong opposition. Some argued that slavery was destructive of government based on republican principles. One critic insisted that slave ownership would destroy the virtue necessary to maintain a republic because it produced “an overbearing and tyrannical spirit, entirely opposite to republican simplicity and meekness.” As Nicole Etcheson shows in The Emerging Midwest, many Americans who had relocated from the Upland South—who knew the plantation system—opposed slavery in the Northwest because they believed it denied them economic opportunity and created “an uneven distribution of wealth and power.” For them slavery contradicted the ideal of the economically self-sufficient, politically independent yeoman farmer.

Harrison’s opponents sought unsuccessfully to have him replaced. In February 1803, citizens of Clark County asked the administration to appoint a governor more attuned to the “principles of liberty.” When Harrison was due for reappointment in 1809, citizens of Harrison County informed Congress that because most people in the territory opposed slavery, they desired a governor who also opposed it. Though Harrison’s foes could not block his reappointment, the next year Congress extended the franchise to all twenty-one-year-old white male taxpayers who had lived in the territory for a year and made officials appointed by the governor, except for justices of the peace and militia officers, ineligible for the territorial legislature. Back in Indiana the territorial legislature repealed the law that held black servants in conditions close to bondage. To reduce Harrison’s personal influence, they relocated the territorial capital from Vincennes to Corydon. Harrison’s rule was being overtaken by democracy; though he remained Indiana’s governor until March 1, 1813, his power was substantially eroded.

Among Harrison’s most important duties as governor was his position as superintendent of Indian Affairs. Most of Indiana belonged to a multitude of tribes—the Delaware, Piankishaw, Potawatomie, Miami, Wea, and Eel River Indians along the Wabash River; the Shawnee, Wyandot, and Chippewa in the north; Kaskaskias in Illinois; Kickapoos in the center of the territory; and the Sauk and Fox on the northern prairie. Tribal land claims often overlapped, but they shared much of the area as common hunting grounds. Both President Jefferson and Governor Harrison sought to dispossess the tribes of the land they occupied. Between 1803 and 1809 the governor signed eleven treaties with representatives of various Indian tribes, by which they surrendered millions of acres of land to the United States. He accomplished this through a mixture of coercion, bribery of corrupt chiefs, purchases of land from tribes that did not properly own the land they were selling, and recognition of Indian leaders who were not recognized by the tribes themselves.

Harrison’s demands for treaties came at a pace that stunned the tribes. At Fort Wayne, on June 7, 1803, the Delaware, Shawnee, Potawatomie, Miami, Eel River, Wea, Kickapoo, Piankishaw, and Kaskaskia ceded land, the salt spring at Saline Creek on the Ohio, and tracts for way stations on the road linking Vincennes with Clarksville and Kaskaskia, Illinois. Later that summer, the Eel River, Wyandot, Piankishaw, Kaskaskia, and Kickapoo gave up more land. There were additional treaties with the Delaware and Piankishaw at Vincennes in August 1804, with the Sauk and Fox at St. Louis in November 1804, and with the Miami, Eel Rivers, and Wea on August 21, 1805. At the close of 1805, the Piankishaw surrendered their claim to land in southeastern Illinois, giving the United States title to thousands of acres along the Ohio River above the mouth of the Wabash.

Harrison’s predatory methods aroused Indian resentment. The most formidable opponents to emerge were the Shawnee brothers Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa. Tecumseh was born, probably in 1768, at or near Chillicothe, on the Scioto River in Ohio; his younger brother Lalawethika, who later adopted the name Tenskwatawa, was born in 1775. Tecumseh became a warrior known for his bravery and intelligence. He was an adept hunter and fighter, who with other Shawnees raided white encampments along the Ohio River, struck frontier settlements in Kentucky, joined Cherokees to make war on Americans in Tennessee, and fought bravely against U.S. forces at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. Much admired among his people, he had become a chief by the time of the 1795 Treaty of Greenville.

Lalawethika was another story. He was boastful, lazy, and often drunk, but in 1805 he experienced a transformation. After falling into a deep trance one night, he spoke of a vision of paradise. Changing his name to Tenskwa...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Part I: The Early Republic

- Part II: Sectional Conflict, War, and Leace

- Part III: From Gilded Age to Roaring Twenties

- The Authors

- Index