![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE CITY

OF THE SEVEN VALLEYS

The early history of Cortland, New York, is told in the story of Moses Hopkins and Jonathan Hubbard, who in 1794 climbed a tall tree on the prominent gumdrop-shaped hill later named Court House Hill, or Monroe Heights, to survey the wooded countryside. Around them seven valleys seemed to converge like the spokes of a wheel. Thick stands of beech, elm, and hemlock concealed the dark valley floors where hunted the bear, wolf, panther, and occasional Indian party. Up the steep hillsides, two to five hundred feet high, large maple, oak, and chestnut trees spread their broad branches to the sunlight. Looking to the east about a mile and a half they could see through the trees the sparkling waters of the stream Tioughnioga, a name given by the Indians that meant “waters with flowers overhanging their banks.” The stream flowed south to join eventually the Susquehanna River on its journey to the Chesapeake Bay.1

Here, surely, was a new land unspoiled and full of promise. Sheltered by nature on the back side of the Appalachian Mountains, the area had been set aside by the New York state legislature as part of the million-and-a-half-acre military tract for use by Revolutionary War veterans as bounty lands. Since few of the veterans chose to settle on their allotted six hundred-acre parcels, at the end of the eighteenth century the area opened for new settlers, speculators, and talented young entrepreneurs like Hopkins and Hubbard.

From 1808, when Cortland became a county—taking its name from New York’s first lieutenant governor, Pierre Van Cortlandt—the progressive leaders of the community struggled mightily to fulfill the vision of the area’s early pioneers. They settled in townships and gave them such classical and historical names as Preble, Truxton, Homer, Solon, Virgil, and Cincinnatus. For the principal villages of Homer and Cortland they laid out broad Main Streets, where wealthy and influential families like the Barbers and Randalls built pretentious and conspicuous houses and gardens. Cortland Village won a competition to be the site of the new county seat. In 1813 the village proudly opened the doors of the new frame courthouse perched on the brow of the hill that had first inspired Hopkins and Hubbard.2

Cortland’s beginnings coincided with a time of general optimism in America based upon an abiding faith in the individual’s ability to achieve his or her potential and, in the process, advance the interests of a democratic society. The 1812–43 religious revivals that overtook Cortland’s evangelical Protestant churches encouraged the individualistic approach to the awakening of religious faith and personal salvation, which shook up the more authoritarian and moralistic Calvinist beliefs of their New England forbears. Education and knowledge were idealized as critical elements of self-improvement. District public schools and church Sunday schools proliferated, as well as institutions of higher learning, including Cortland Academy at Homer (1819–73), Cortlandville Academy at Cortland Village (1842–69), and the New York Central College of McGrawville (1849–60). In its day, New York Central College represented a bold experiment in liberal education. Founded in 1848, it opened its doors to all, “regardless of sex, color or religious belief.” In the early years of the college, about a third of the students were black, and half were women. Both blacks and women could and did serve on the faculty.3

But the inspired work of the county boosters faced many obstacles. Poor, gravelly soil, long winters, and short growing seasons limited the county’s major agricultural crops to wheat, corn, oats, and potatoes. By 1845 two-thirds of the productive land had been developed, with most of it (75 percent), of necessity, devoted to raising livestock, dairy products, maple sugar, and hardy varieties of fruit trees.4

At the same time the surrounding hills isolated Cortland from the full benefits of the Erie Canal, which had been completed across the central part of the state in 1825. Without a supportive transportation system, commercial agriculture and manufacturing were slow to develop in Cortland. Adding to the county’s economic woes, by 1840 the flow of water in the Tioughnioga had diminished to the extent that the flat-bottomed “arks” that had once carried gypsum, salt, oats, potatoes, pottery, whiskey, and other Cortland products to market could no longer float downriver on spring freshets from launch points near the community of Port Watson. By 1860 the county lagged behind most other New York counties in manufactured value per capita. With a sluggish economy and productive land no longer readily available, population growth slowed—only 0.3 percent per year from 1830 to the Civil War.5

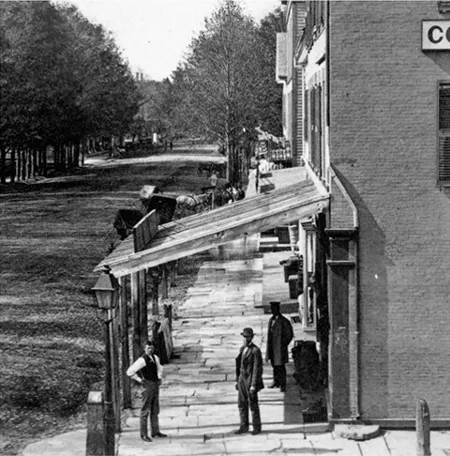

Cortland Village, New York, around 1870. View of Main Street

looking north from Port Watson Street. Squires Hall was located in this block. (Author’s collection)

In national politics the county marginally voted Whig from 1828 until 1856, then Republican for the presidential elections of 1856 and 1860 (favoring Abraham Lincoln 3,893 votes to 1,712). For the most part, the county supported Whig-Republican policies favoring “internal improvements,” economic growth, the temperance movement, and opposition to the extension of slavery into the western territories. While most residents considered slavery a national curse and anathema to a democratic society, they did not go so far as to embrace the abolitionist cause of immediate slave emancipation in the South or the concept of social equality for free blacks. When John Thomas, a member of the state assembly and staunch abolitionist, joined forces with some church and community leaders to form Cortland’s first antislavery society in 1837, he and his colleagues were labeled “fanatics.” The prominent and influential Democrat Henry S. Randall led the attack against this group in the Cortland Advocate. He spoke against what he identified as Thomas’s “scheme of agitation,” which would result only in the “embroiling neighborhoods and families—setting friend against friend—overthrowing churches and institutions of learning—embittering one portion of the land against the other.”6

Cortland’s pro-abolitionist minority found political voice in the Liberty party, organized locally in 1841. Although the Liberty vote in Cortland showed some strength in the 1844 elections, by 1848 resident Samuel Ringgold Ward, a former slave and now a Presbyterian minister, could garner only 120 county votes in his bid for the state assembly on the Liberty ticket. Embittered over his defeat, Ward left the county for greener pastures, declaring that Cortland represented for him “more of the foolishness, wickedness, and at the same time the invincibility of American Negro–hate, than I ever saw elsewhere.”7

In general, Cortland residents shunned the abolitionist demand for collective social action and change in the service of what they perceived to be the radical and unlawful political and social agenda of a few. When the Reverend John Keep in 1833 strayed from the gospel to preach abolition and social reform from his pulpit in the Homer Congregational Church, he was forced to resign. John Thomas eventually left Cortland for Syracuse, Onondaga County, where he thought he could more fruitfully promote Liberty party causes. The New York Central College, derisively referred to as a “nigger” college by some, closed its doors in 1860, not only because of the controversial racial issues of the day that embroiled it but also because of community indifference and lack of local financial support.8

Like many American communities in the 1850s, Cortland County staked its future on the coming of the railroad. The Syracuse, Binghamton, and New York Railroad, which ran across the county through Homer and Cortland Village, began operation in 1854 under its first president, Judge Henry Stephens of Cortland. Dignitaries and supporters celebrated the long-awaited completion of the road on October 9, 1854. On that day citizens gathered near the Tioughnioga just south of Cortland Village to drive the final spike. As two locomotives touched their cowcatchers, symbolizing the official opening of the road, cheers from the crowd competed with screeching train whistles and the thunderous sound of cannon fired from Court House Hill.9

The railroad opened on October 18, 1854, with an excursion train made up of three locomotives and twenty-eight cars, filled at one point with about two thousand “merry,” albeit crowded, passengers. Throngs of people gathered beside the tracks along the route to salute the passing train with cheers, banners, music, the firing of cannon, bonfires, and the ringing of church bells. At an official Cortland stop the local ladies set out tables near the station laden with many good things to eat and drink for the passengers. A Cortland singing group, the “Melodeons,” rode the train for a time, singing an ode to the people’s faith in the ability of the iron rails to unite Cortland with the outside world in a wondrous future of mutual progress and growth. They sang:

For lo we live in an iron-age,

In the age of steam and fire.

The world is too busy for dreaming,

and has grown too wise for war,

So, today, for the glory of science,

Let us sing of the railway car.

Ironically, when conflict finally came, the railroads would serve as its indispensable agent, contributing to warfare’s destructive power.10

On the eve of the Civil War, few could deny that Cortland County, despite its often difficult early history, had achieved a privileged maturity and was poised for a bright future. In 1855 the county boasted ninety-five merchants, twenty lawyers, fifty-six clergymen, forty-nine doctors, thirty-two inns, and 184 schoolhouses. In 1860 the population had reached 26,000, including sixteen African Americans and 1,300 foreign born (mostly Irish and English). There were fifty-five churches in the county (including nineteen Methodist and eleven Baptist), three newspapers, and three academies or secondary schools. The principal villages of Homer and Cortland had shown a 31 percent population growth over the previous three decades, to reach totals of about 1,600 and 2,000 residents, respectively. This ready and able workforce was to support the spurt in local manufacturing that would come in the 1870s.11

As sectional animosities intensified during the heated presidential election campaign of 1860, Cortland residents increasingly became drawn into national events. In the evenings, after dinner, those living in Cortland Village would often walk down Main Street to the dry goods stores of S. E. Welch or James S. Squires to discuss the issues of the day. Young George Edgcomb, who boarded with Welch and clerked in his store, recalled that the New York City papers, especially Horace Greeley’s Republican New York Tribune, would be read out loud to the gathering by the store proprietor or his designee. The paper spoke out against the growing intransigence of the South concerning national economic and political matters, especially the volatile issue of extending slavery into the West. An often-told story indicates the temper of the times. It seems a young Cortlandville boy returning on the train from Syracuse with his mother brought smiles to the other passengers when, after the brakeman announced the town “Preble,” he spoke up: “Mama, what made the man open the door and holler rebel?”12

However, before Fort Sumter, in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, came under the fire of Southern forces on April 12, 1861, few in Cortland thought that the sectional differences between North and South would lead to war. William Saxton, a student at Cincinnatus Academy, expressed the common notion that there would be no fighting. “All we had to do,” he thought, “would be to show those Southern fellows that we could not be browbeaten any longer; that if we put on a bold front . . . they would yield and all would be settled.”

After Sumter fell on April 13 and President Lincoln called out the state militias, the enthusiasm for military action among the general population, if not their leaders, knew no bounds. The Cortland Republican Banner of May 1, 1861, reported that since April 12, “nothing else was talked of, and nothing thought of but punishment to the rebels.” One Cortland soldier, John Lane, recalled from those days that “every time they went anywhere or met anybody all they heard was War! War! War!” “What a picnic,” Saxton and his schoolmates now thought, “to go down South for three months and clean up the whole business.”13

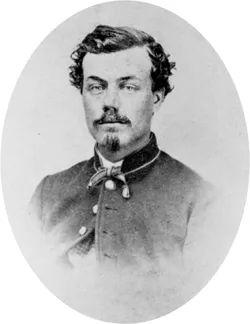

George Edgcomb, recruit. (Author’s collection)

George Edgcomb, veteran. (Author’s collection)

As Cortland County braced for war, the initial opportunities for its young men to serve in the military were limited. Lincoln’s April 15 call for 75,000 men obligated New York to a quota of 13,280 officers and men, or seventeen of its militia regiments. On the books of the state militia organization, Cortland County had two “active” companies of infantry and one of artillery, in the 42d Regiment, Nineteenth Brigade, Fifth Division. Actually, however, like most of the state militia regiments, the 42d was deficient in supplies and manpower and was in no condition to take the field.14

The situation changed on April 16, when the state legislature authorized Governor Edwin D. Morgan to enlist into state service about thirty thousand “Volunteer Militia” for two years’ service. These men would be formed in companies and then organized into regiments by state authorities under state militia laws but “without regard to existing military districts.” Thus, as the Federal government began accepting New York’s available organized militia regiments (the famous 7th New York State Militia left the state on April 19, followed by ten others), the door opened for communities across the state to raise their own independent companies for active service. As a result, in about three months’ time New York would accomplish the remarkable feat of organizing, equipping, and making available to the Federal government an additional forty-six infantry regiments, mustering about 38,000 officers and men.15

As the state prepared for war, Cortland citizens put pressure on their leaders to begin organizing county resources to respond to the national crisis. Notices went up in Cortland Village announcing a war meeting to be held at the courthouse on the evening of Saturday, April 20. That morning the Stars and Stripes, often homemade, suddenly appeared throughout the village, reflecting, as...