![]()

PART I

Poetry

![]()

1

The Poetry of Paul Laurence Dunbar and the Influence of African Aesthetics

Dunbar’s Poems and the Tradition of Masking

LENA AMPADU

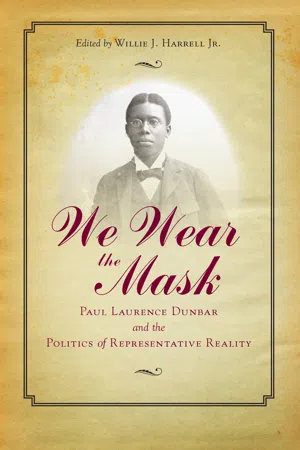

HIS FAME HAVING RESTED MOSTLY on his dialect poems, which have origins in the minstrel tradition, many critical studies examine Paul Laurence Dunbar’s work and its relationship to the slave past in America and to the tradition of minstrelsy popularized in nineteenth-century America. By 1899, Dunbar was widely acknowledged as a master of poetic technique who commanded respect in the literary world at home and abroad. He began losing his prestigious status in 1922 during the Harlem Renaissance with the publication of Johnson’s Book of American Negro Poetry, which made way for the poetry of the New Negro. Later, after the civil rights movement, consistent with the tenor of the times, which called for more direct social protest and often comic depictions of blacks, Dunbar continued losing popularity and was often heavily criticized because of the absence of racial affirmative pride in his poetry. He was generally cited as a kind of tragic black figure desiring to be accepted by predominantly white audiences.1 A close and careful examination of the breadth of Dunbar’s poems, both the standard and vernacular varieties, reveals an often neglected link to the oral traditions of the African past and shows his poetry to convey the tenets of racial consciousness and pride that would later characterize the Harlem Renaissance. To rectify this lack of attention to the debt that Dunbar’s poems owe to African traditions and aesthetics, this chapter will examine his poetry by identifying the African retentions in his poetry and examining the transformation and revision many of these retentions underwent after arriving in the New World to become African American vernacular cultural forms.

In 1921, James Weldon Johnson, in his preface to The Book of American Negro Poetry, lauds Dunbar as a poet whose skill and artistry had their beginnings outside dialect poems. However, Dunbar lamented the restrictive role that larger society had given him as an author of dialect poems: he launched a public protest against this in the often-quoted lines of one of his poems: “But ah, the world, it turned to praise / A jingle in a broken tongue.”2 His explanation for why he seemed to placate white audiences by assuming the minstrel role and writing poems advancing black stereotypes and glorifying life on the plantation can be found in his poem “We Wear the Mask.” In the tradition of African verbal discourse filled with dualities, he explains that one wears “the mask that grins and lies” to prevent the world from being “over-wise, / In counting all our tears and sighs.”3 Having originated in Dunbar’s poem, this use of the term “masking” serves in literary and language conventions today “as both a rhetoric of deception and a kind of cultural ‘shibboleth.’”4 Revisionist criticism of Dunbar’s dialect poems considers them to be “masks in motion” that act as facades for the messages communicated in the poems as well as the cryptic messages central to the African American experience.5

Although Dunbar probably did not have the African mask in mind when he wrote this poem, if one views his poem purely within an African context, one can interpret it as both a literal and figurative reference to a mask. The mask, a decorative carving usually made of wood or stone, can be worn during African ceremonies for different functions and can have the same kinds of dualities as language. In Africa, which one thinks of as traditionally having a purely oral culture, a mask can be considered a form of writing; such a view thus elevates African societies to ones of “mixed orality,” in which writing coexists with orality.6 We might view Dunbar’s poems in a similar way: they are produced within a literate mainstream culture, but they reflect the oral culture of the people about whom they are written. His poems are also infused with the various strategies of orality, some being written strictly in dialect, while others are written strictly in Standard English. Still others are a fusion or a mixture of the two varieties of English.

The word “masks” can refer to the types of face coverings that people wear at celebrations throughout the African diaspora, for example, during Mardi Gras in New Orleans or Carnival in Brazil or Trinidad. When I introduce this poem in my literature classes and ask students to define the word “mask,” the consensus usually is that the mask is a facade, and they usually admit that the poem could refer to a mask of revelry much like that of the clown in Smokey Robinson’s “Tears of a Clown.” The lyrics of Robinson’s song facilitate their comprehension of the message of “grinning and lyin’” in comparison to the character of the clown in the song, who wears a mask that shows a happy outward appearance but masks the clown’s true feelings of sadness and unhappiness.

Further drawing from an aesthetic originating in the African homeland, Dunbar, preserving the legacy of the African griot, created poems in the genre of the African praise poem (poems written in celebration of an honorable community member, leader, or event). An important dimension of African oral poetry, the praise poem is best understood and appreciated when preached, sung, or recited. African poems are direct and immediate but celebrate heroes and historical events and are concerned with the poetry’s immediate effects.7 Several of Dunbar’s poems paid tributes in this fashion, including “Black Samson of Brandywine,” “Douglass,” “Booker T,” “The Colored Soldiers,” and “When Malindy Sings.”

As African praise poems, his “Black Samson of Brandywine” and “The Colored Soldiers” examine the plight of black soldiers individually and collectively. In the 1930s, literary critic, poet, and professor Sterling Brown labeled these “race-conscious poems,” and Dunbar labeled himself a “race representative.” He declared of his role, “My ambition is to make closer studies of my people.”8 In the poems, Dunbar heaps praises upon the soldiers, “the noble sons of Ham,”9 who, like his father, gallantly fought in the Civil War wearing the uniform of the Union army. These brave soldiers often fought just as courageously as the white soldiers but faced more imminent danger of being executed by rebel soldiers, who would kill them rather than take them as prisoners of war.10 Since the heroic deeds of the black soldiers were never publicly acknowledged, Dunbar bestows this honor upon them in his “The Colored Soldiers.” In the same vein, he praises Black Samson, who fought mightily against the British in the Revolutionary War in southeastern Pennsylvania. Using words that convey pride in Samson’s and his own heritage, Dunbar labels him

An ebony giant,

Black as the pinions of night.

Swinging his scythe like a mower

Over a field of grain.11

In his description of Samson, Dunbar anticipates the positive comparisons of blackness to the night that later writers like Langston Hughes used to extol the beauty of blackness:

I am a Negro:

Black as the night is black

Black like the depths of my Africa.12

Though Dunbar uses the term “colored” in his poem valorizing the soldiers who fought in the Civil War, a term that originated among the mixed-race group, he reverses the earlier negative connotations of the word “black” that writers like the eighteenth-century poet Phillis Wheatley and the nineteenth-century political writer Maria Stewart had used in their writings. In the line “Remember Christians, Negroes black as Cain,” from Wheatley’s “On Being Brought from Africa,”13 blackness is associated with the evil Cain, the first man to commit a murder in the Bible. Later, Stewart would write, “Though black your skin as shades of night, / Your hearts are pure, your souls are white.”14 Although she, like Dunbar and Langston Hughes, compares blackness to the night, she contrasts blackness with the purity and whiteness of the soul. Stewart, therefore, links darkness with sin and evil, as does Wheatley.

During his exceptional career as a poet, Dunbar came into contact with several nationally known leaders in the African American community, including Frederick Douglass, Alexander Crummell, W. E. B. Du Bois, Mary Church Terrell, James Weldon Johnson, Charles Chesnutt, and Booker T. Washington, all of whom advanced the educational goals and/or political aspirations of African Americans. Since all these leaders were engaged in social and political struggles for African Americans, Dunbar’s friendship and association with them helped counteract the belief that he was merely a minstrel who avoided social protest. In fact, Du Bois, who often appeared at programs with Dunbar, labeled him a “protest writer.”15 Mary Church Terrell, a women’s rights activist and spokesperson against lynching, was a neighbor and friend who maintained a lifelong correspondence with him. She dubbed him “poet laureate of the Negro Race,” a title that survives today.16

Dunbar wrote poems extolling the virtues of several of these activist leaders. In 1893, Frederick Douglass praised Dunbar when he read his poetry at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. In turn, Dunbar praised Douglass in the poem “Frederick Douglass,” originally called “Old Warrior,” which he dedicated to him upon his death in 1895. In “Frederick Douglass,” Dunbar calls Douglass “a spirit brave” who “has passed beyond the mists.”17 Calling him a son of Africa, using the Eth...