![]()

Chapter 1

“Local Communities Are No Match for Industrial Corporations”

Lima, the county seat of Allen County, is a weathered industrial city of about forty thousand people, set against the flat and prosperous farmlands of northwest Ohio. It still possesses a certain charm. Local people can boast of a set of nearly new schools, a few grand old boulevards where the city’s early industrialists once lived, and wide, tree-lined streets with some of the cheapest housing of any similar place in America. Nonetheless, the city seems haunted by the question of whether, when its financial magnates left, they might have taken its best days with them. Even as fierce a defender as its longtime mayor remembers that when he first drove into Lima as a young man, his first impressions were of a beaten-down old city that “hadn’t taken very good care of itself.” Three decades later Lima’s face still seems worn and gray, especially when compared with the tracts of comfortable housing developments on its edges. Lima’s urban thoroughfares are pockmarked with vacant lots and its most memorable physical characteristics are the number of railroad crossings that nearly barricade off its downtown. In fact, one cannot enter Lima without being reminded of the constant physical presence of trains. The city’s heart consists of two massive hospitals, some public buildings and a varied collection of small restaurants and businesses spread over about eight blocks, and a business district tenaciously holding on against the attractions of the malls in the suburbs west of town. It is the kind of town perennially described by outside journalists with words like “blue-collar” and “gritty.”1

Lima is also an island in every sense except the strictly geographic. In the spring and summer, it is an urban island amidst limitless green fields of corn and soybeans. Economically and demographically, it remains an island of working-class sensibilities surrounded on all sides by middle-class suburbia. These are the “townships” that remain politically separate from the city while fully dependent on its services. The city is a political island as well, though one has to dig a bit deeper to fully see this. As the national left-leaning journal the Nation informed readers in 1996, Lima was “a rock-ribbed Republican bastion, a town that still brags of going for Goldwater in 1964.” In fact, that claim isn’t true; Lima went for Johnson that year by a small margin. Even so, conservative political instincts still run deep across Allen County and have been reinforced for decades by the city’s newspaper, the Lima News, which for a generation now has served as a faithful, steady fount of libertarian free-market ideology. On the other hand, amidst the vast sea of Republican governments that dominate northwest Ohio, Lima’s residents have, for more than two decades, retained enough blue-collar roots to regularly elect a feisty and progressive Democrat as their mayor. Not surprisingly, the city’s newspaper and its mayor have generally locked horns, except for one short period, the greatest crisis in the city’s modern history, when they joined in an unlikely but effective partnership.2

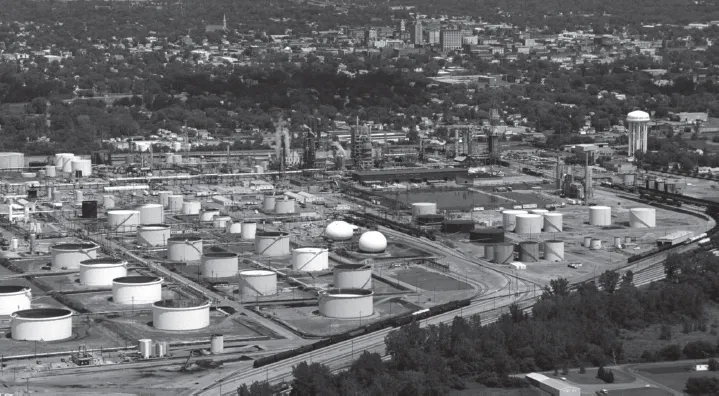

The Lima refinery in the foreground, with downtown Lima behind. Photo courtesy of the Lima News.

Main entrance gate, BP Lima Refinery, mid-1990s. Photo courtesy of the Lima News.

Lima is an island in another way, too, one that can be fully appreciated only by traveling south on Main Street from the business district, over the Ottawa River, past increasingly ramshackle homes to stand on a railway overpass. There to the west, just south of the city limits, unfolds a truly alien world. It is a scene that could be lifted from a futuristic movie: huge sculpted scaffolds of pipes emerging from fields of asphalt, dozens of valves emitting steam, blue flames flaring into the sky, all tended by a uniformed army in hard hats. The functionaries of this world speak in a whole different vocabulary, conversing knowledgeably of matters like the cat cracker, alkylation, throughput, and BPDs. At night the place burns with the glitter of a thousand orange lights while the machinery throbs on relentlessly. Local people tell the story of a visitor to the city who was once staying in a motel west of town. He woke up in the middle of the night, saw an immense orange glow on the southern horizon, and immediately concluded that half the city was on fire. Only after he had jumped into his car and driven to the south edge of town did he realize that Lima was not on fire. It was only another normal working night at the city’s oil refinery.3

The Lima refinery at night, mid-1990s. Photo courtesy of the Lima News.

Perhaps it is the immensity of the place, along with its bizarre panorama, that has secured for the refinery such a prominent place in both the local economy and the city’s very identity. It is the largest single taxpayer in the county, the biggest single consumer of local water and electricity, and, with a payroll of upwards of $31 million, one of the largest local employers. But there is more to it than that. The plant has operated continually since the days of John D. Rockefeller, more than a century ago. Succeeding generations of local people have worked there, often generations of the same families, and most of them have lived and spent their salaries in the Lima community. Through such ties, the plant has so deeply cemented itself into the unspoken consciousness of the city as to become something close to iconic. “It’s one of foundations of the city,” a refinery staffer observed. “It’s like it’s in peoples’ blood or something … you’re always aware of its presence.” A drawing of an oil derrick and the “eternal flame” of the refinery dominates the city’s flag.4

Finally, the very presence of the city’s refinery means that Lima stands out as an island of possibility in the larger landscape of deindustrializing America. For many similar communities around the world, this has become a relatively bleak and barren terrain. By all standard logic of the era—and especially by the intentions of British Petroleum (BP), the longtime owner of Lima’s refinery—the sprawling facility on the south edge of town should no longer exist. In the mid-1990s, over the anguished but seemingly futile protests of local people, BP decided that the plant no longer fit into its current corporate profile and moved to shut it down. At that time, BP was one of the most powerful and wealthy corporations in the world, and Lima had already been so staggered by successive waves of plant closings that it had come to symbolize the national economic dislocation of the “rust belt.” The refinery—and, to some degree, the larger Lima region—stood poised to join a hundred other such locales already carelessly discarded onto the industrial scrap heap. Yet Lima’s refinery did not close. It continues to pump out oil and generate wealth, to the benefit of both its corporate owner and the regional economy. It does so because of the strenuous efforts of a range of dedicated people, both inside and outside the plant gates, who were determined to secure for themselves a different future than the one dictated by BP. The story of how they succeeded reveals previously hidden possibilities in an era of deindustrialization. What if corporate decisions are not immutable and absolute? What if communities can still imagine themselves, at least to some degree, as masters of their own fates?

“Birth certificates and death sentences to entire communities”

Part of what makes the encounter between BP and Lima such a compelling story is that both entities were struggling against forces and economic calculations larger than themselves. Throughout the United States, large corporations, responding to an intensely competitive economic environment, sought to close down outdated industrial plants. The reasons behind such closures came as small consolation to the stricken communities these corporations left behind, however. As historian Stanley Buder has recently observed, corporate America underwent a signal period of restructuring through the 1980s. Marked by a series of leveraged buyouts and hostile takeovers, this restructuring may have ultimately strengthened the business sector, but in the interim it meant profound uncertainty for corporate heads. The “clear message had been sent out” to business CEOs: either “act boldly or lose your job.” A revolution in corporate governance, beginning about the same time, fed the new ruthless search for profits. Faced with the prospect of hostile takeovers by a newly emerging class of corporate raiders, CEOs faced a stark choice. As summarized by corporate theorist Marjorie Kelly, they had to either “start wringing every dime from operations (sending jobs overseas, selling off weak divisions, laying off thousands), or be taken over by someone who would.” One study of corporate heads of Fortune 500 firms from 1996 to 2000 explored what happened when stock analysts downgraded their recommendations about purchasing company stock by just one grade, from “buy” to “hold”: within six months, almost half of the top executives of such companies had lost their jobs.5

Oil companies in particular faced an intensely competitive economic environment, where their ability—or inability—to function at the point of greatest efficiencies could spell the difference between a successful year or a disastrous one. The oil industry has always suffered from extremely high overhead; as business scholar Geoffrey Jones noted, “the investments required to develop an oil field or build a refinery were extremely large” and “entailed high fixed costs. As a result, small variations in price or in output had a relatively powerful effect on profits.” This was a particularly worrisome trend for big oil executives in the 1980s, when they faced a sudden and unexpected drop in oil prices because of the global “oil glut.” It was in this context that BP began to consider reducing its refining capacity and ultimately set events in motion that would lead to its decision to close its Lima facility. Reporting on the plant closings by international oil companies in the 1990s, journalists noted that it was no longer enough for big oil executives to merely report sumptuous profits; they had to worry about the extent of their profit margins, whether their efficiencies were at peak, and whether investment in a specific plant would produce an even higher rate of return if applied elsewhere.6

Civic leaders faced with plant closings had to sort through their own set of grim calculations. At first glance, it was not clear why the Lima region’s future should be any different from that of hundreds of similar communities, whose municipal leaders had discovered their relative powerlessness when the reigning corporate partner had decided to close up local operations and move elsewhere. Between 1962 and 1982 alone, the country witnessed the closure of more than one hundred thousand manufacturing firms, each employing more than nineteen workers, a full fifth of them in the five states of the old industrial Midwest. From 1979 to 1986, this region had suffered a 19.3 percent decline in manufacturing employment, losing nearly 950,000 full-time manufacturing jobs. These job losses originated in a variety of complex underlying economic factors (see chapter 4 for greater detail). By the 1970s, many U.S. corporations faced increased overseas competition and rapidly declining profits. Plant closings therefore seemed, on their face, a natural and inevitable end to the industrial life cycle. Corporate managers quickly moved to pin the blame on an overpaid, unproductive workforce and aging, obsolete equipment. “Yet the closing of an obsolete mill,” one analyst has summarized recently, “was often the direct result of management’s failure to modernize or their active decision to invest somewhere else.” Technological innovations, such as the computer and communications revolution and containerized shipping, facilitated the decisions of corporate managers to shift their production elsewhere, to low union areas in the American South or, even better, overseas, wherever the prevailing wages were lowest and the hand of governmental regulation the lightest.7

Cities like Lima also face a marked disadvantage in corporate economic decisions because of the privileged place of capital in U.S. corporate law and history. By the later twentieth century, U.S. corporations had been working the legal system for at least a century, successfully attaining a whole range of new powers. In fact, they have become something akin to a new kind of legal entity altogether. In the first one hundred years following ratification of the U.S. Constitution, American courts wrestled with two different readings of the essential nature of corporations. One view held that the corporation was an artificial being, a creation only of laws for specific purposes, and thus could be readily restricted—or even dissolved—by the popular will. The other view held that corporations were “natural entities,” real beings with a separate existence deserving of basic rights. Understandably enough, corporate leaders strongly favored the latter view, and thus, as legal scholar James Willard Hurst has noted, through much of the nineteenth century, corporations approached federal court under the “odd fictions” that they were citizens.

This latter interpretation of the nature of corporations was given great weight by two key legal decisions, which together facilitated the rise to dominance of great corporations in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The first of these was the Santa Clara decision of 1886, in which the U.S. Supreme Court issued the bizarre but foundational legal opinion establishing in law the fiction that corporations were real persons, deserving of every protection as natural beings under the Fourteenth Amendment. This amendment had been ratified in 1868, primarily to clarify the status of recently freed slaves, thus establishing the normative definition of U.S. citizenship. Corporate lawyers quickly used the Santa Clara ruling to induce courts to strike down hundreds of laws regulating corporations and in other ways restricting their autonomy as real persons. In the first half-century following the Santa Clara ruling, noted Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black in 1938, more than 50 percent of the cases invoking it did so in order to extend the rights of corporations; less than a half of 1 percent of the cases involved the issue of racial justice. In recent decades, corporations have used the decision to appropriate many of the other constitutional protections commonly awarded living human citizens under the Bill of Rights. In the Bellotti case of 1978, for example, the Massachusetts Supreme Court struck down a law restricting corporate political advertising because of the basic American right to free speech.8

The second watershed legal decision solidifying corporate power came in 1919. In Dodge v. Ford, the Michigan Supreme Court ruled in 1919 that a corporation existed primarily to enrich its shareholders, that this was its essential purpose. Hence a corporate action aimed at any other end—to, say, soften the effect of plant closings on its partner communities—became essentially untenable. Technically, these or any other expressions of corporate social responsibility were illegal. In the emerging political and economic climate of the Reagan-Bush decades, when paeans to the virtues of the unrestricted free market reverberated with near-religious conviction, new devotees of this view did not shrink from such expressions of corporate social irresponsibility. Instead, they celebrated them. “The one and only … social responsibility of business,” the Nobel Prize–winning economist and free-market apostle Milton Friedman proclaimed, is to “increase its profits.”9

In the sphere of corporate law, corporations have thus come to possess capacities that are nearly cosmic. They are persons entitled to every right that real U.S. citizens enjoy, yet at the same time they are something like superpersons. They are immortal; they cannot be killed. They may legally be persons but they can officially feel no human emotions like guilt or shame. While on the one hand, they can devour one another, on the other, if its suits their interest, they can break apart like amoebas into constituent parts, which all have the same privileges as the mother body. They can disband themselves in one location and then suddenly rematerialize states or oceans away. By the 1930s, the legal powers accumulated by large business enterprises seemed so all-encompassing that New Deal theorist Adolf Berle could only conclude that “the rise of the modern corporation has brought about [such] a concentration of economic power that it can compete on equal terms with the modern state.”10

Against this awesome array of corporate powers, individual communities labor to safeguard their own interests under a variety of marked disadvantages. Their powers are weak compared to those of state or national governments. Faced with a harmful decision from a large corporation, therefore, the immediate municipal response of many local governments is to enlist the help of a governor or senator. Yet if such officials are disengaged, or if the cor...