![]()

The Cuban Works

To Have and Have Not

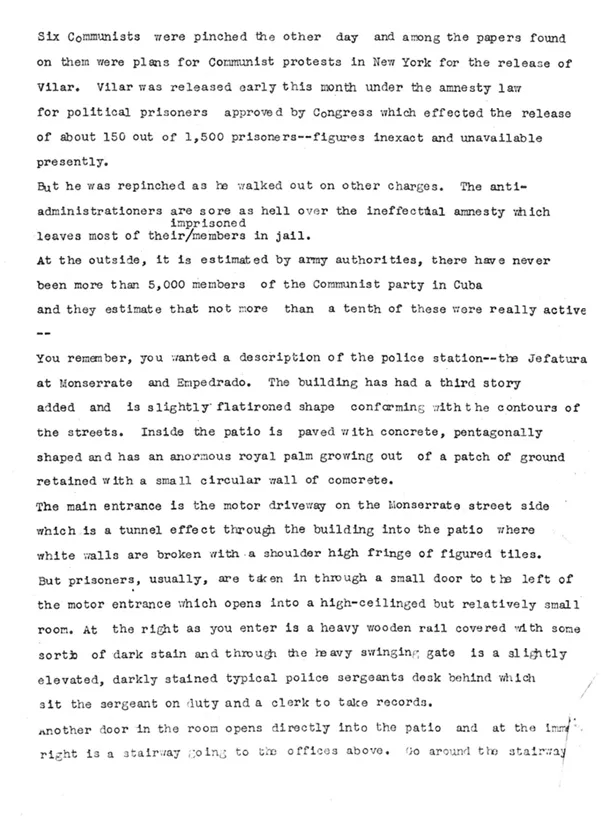

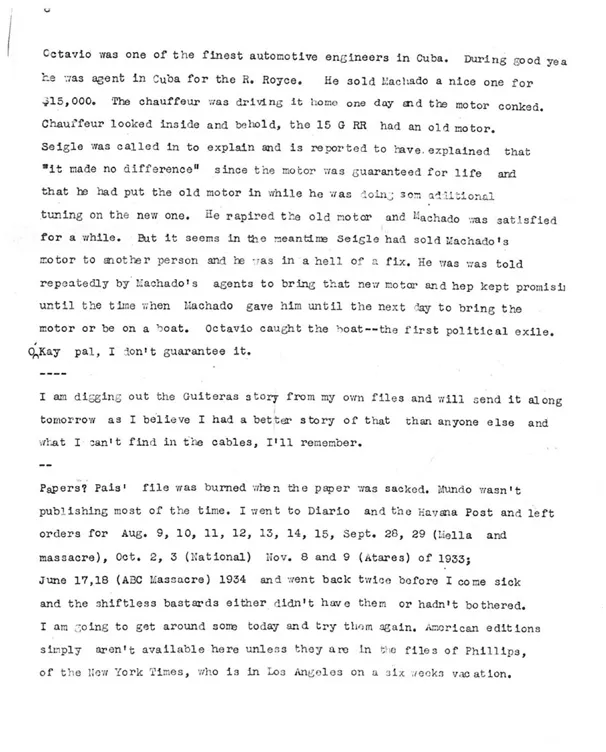

Photograph sent to Ernest Hemingway by Richard Armstrong of two dead men lying on a dirt road. It was inscribed “Pupille f.16 diaphragm 22 bright sun. Being gentlemen obnoxious to the govt.” and stamped “Agfa-Brovira.” Ernest Hemingway Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

![]()

The State of Things in Cuba

A Letter to Hemingway

RICHARD ARMSTRONG

Introduction

Larry Grimes

To insure accuracy in his portrayal of the more recent revolutionary activities he wanted to include in To Have and Have Not, Hemingway asked journalist Richard Armstrong to provide him with a summary of detailed newspaper accounts of the uprising. Hemingway had known Armstrong since at least 1933, when Armstrong had served as photographer for the Cadwalader marlin expedition. On August 27, 1936, Armstrong sent Hemingway a photograph (reproduced here) and a thirteen-page letter full of information. Hemingway subsumed the information in Armstrong’s letter into the text of the novel, sometimes almost verbatim, in the manner of his earlier work with newspaper materials in A Farewell to Arms. In the manuscript of the novel, this material was included in what Hemingway designated, in his one-page outline of the novel, as “the Story of the Dynamite trip and its capture.”1

That important Cuban material was deleted from the manuscript of To Have and Have Not as Hemingway edited it for publication.2 Scenes from the revolution were cut, together with a very important reflection on the nature and purpose of terrorism by Tommy Bradley, a central character, that justifies terrorism as a part of revolutionary activity. It begins with the observation that when people live in a state of absolute tyranny, there is no noise. Freedom of speech is denied. Protest is throttled. According to Bradley, in the silence that tyranny creates one must use dynamite, dynamite that kills. Bodies must be found. The revolutionaries are not seeking approval. Such violence is not to be liked, but in a revolution it is necessary because it creates “the uneasiness that come[s] before conscience.” The reflection, referring to the necessity of dynamite and, the need for undeniable noise, affirms the nature and purpose of terrorism and concludes with words that point toward For Whom the Bell Tolls: “The victory grows in the soil of defeat … There is no hope in terrorism. It is a noise you make when you are hopeless.… But the dynamite for the bridges is for when we fight again. And that is all I live for now.”3

Notes

1. Ernest Hemingway, Outline of To Have and Have Not, Hemingway Collection, John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library, Boston, MA (hereafter, JFK).

2. Ernest Hemingway, Item 212, Hemingway Collection, JFK.

3. Ibid., Pt. 5 of 5: 162.

Works Cited

Hemingway, Ernest. Item 212. Hemingway Collection, JFK.

———. Outline of To Have and Have Not. Hemingway Collection, JFK.

Reynolds, Michael S. Hemingway’s First War: The Making of a Farewell to Arms. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 1976.

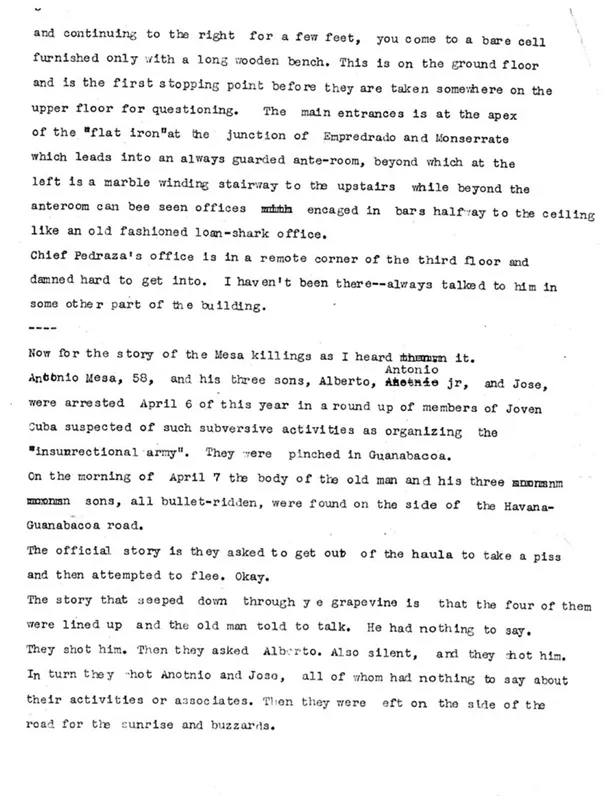

Following pages: The source of the scanned letter is TLS Dick, 27 August 1936, 7pp. Ernest Hemingway Personal Papers, Incoming Correspondence, Armstrong, Richard. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.

![]()

Selection from “It is hard for you to tell,”

Chapter Three of Cuba y Hemingway en el gran

río azul (Cuba and Hemingway on the

Great Blue River)

MARY CRUZ

TRANSLATED BY MARY DELPINO

In the art of literature, an image is not fixed on paper in the same way as a sculpture is set in stone or a painting on canvas, or even music on a score. The fictional world that the reader perceives is reconstructed in his imagination, bit by bit, from written clues, much like a jigsaw puzzle is put together as each piece is found and added.

The frequent gaps or the seemingly random order in which information is supplied, as well as the subjective distension and contraction of time, are not fortuitous. They are technical devices deliberately employed to achieve certain effects aimed at a specific objective. When those effects are achieved and that goal is reached, the work has surpassed the threshold of the ordinary to become something elevated: art. That is why, in my opinion, To Have and Have Not (THHN) is a work of art.

What appears to be a clash between form and content is resolved through a single all-encompassing meaning. Hemingway himself was not satisfied with the result (Lidskii 282). Nevertheless, after reading the three stories that make up the novel—“One Trip Across,” and “The Tradesman’s Return” (previously published separately), and the one that gives this novel its title—the reader has a complete and coherent view of the protagonist’s psychology and life, but still can’t expel from his mouth the bad taste of a sick society in a chaotic world that victimizes the main character. The reader has witnessed the painful process of a man’s awakening consciousness. He has participated in an unforgettable experience.

The novel must be considered a structural unit and not the mere sum of its parts. The conflict between the haves and the have-nots is already set forth in the title, not surprising for those of us who, like Hemingway, know Cervantes. In chapter 20 in the second part of Don Quixote de la Mancha, Sancho Panza says to his master: “There are only two lineages in the world … the haves and the have-nots” (Cervantes 705). In Hemingway’s novel, that conflict gradually grows in definition and clarity, building to its culmination in a powerful picture of the moral bankruptcy of many of those who have all.

The length of each part matches the size of its geographic setting: Cuba, Key West, and the mainland United States (which in the novel represents the oppressive social order). In the second and third parts, the reader is transported on an imaginary journey from the Gulf of Mexico to Key West; then from Key West to the mainland.

All three stories offer a proportionally compressed reproduction of reality. Figuratively speaking, the third story is an inverted, magnified reflection of the first story, much like the reflection of an image on the retina or a photographic lens, but reversed.

The “healthy animal” that is Hemingway’s main character does not “suddenly” become “vaguely political” (Atkins 46). The story describes the process through which his ignorance is replaced by knowledge as circumstances force this common man to face in real life the dilemmas that philosophers solve in their chambers.

It would seem irrelevant to analyze each story separately. However, the slight, albeit significant changes made to each in transforming it into a component of a larger work, as well as the significance that each part takes on within the structure of the whole, not only allow but demand both separate and general analytical approaches.

“One Trip Across”

Written in 1933—a time of intense revolutionary activity in Cuba—“One Trip Across” was published by Cosmopolitan in April 1934 with ostentatious title and by-line, plus illustrations. The timing of the publication deserves special attention.

It is worthwhile to recall some history. Precisely on August 7, 1933, while he was waiting to board the ship that would take him to Europe on the first leg of a trip to Africa, Hemingway had witnessed one of the most horrendous massacres perpetrated by the henchmen of the tyranny that was strangling the island.

Later, while he was on the high seas, he would learn that Dictator Gerardo Machado had been overthrown while Benjamin Sumner Wells, Washington’s envoy to Havana, used all sorts of trickery to prevent the inauguration of a progressive government on the island. For a brief period, the people were victorious. But reactionary forces were too powerful, and Cuba fell once again under the control of successive puppet governments propped up by the United States administration.

At the time the story was published in Cosmopolitan, however, the people’s victory was still a reality. All of this explains the editor’s offensive and misleading introductory remarks: “Along the coast of Cuba, land of violence, a giant marlin rises to the bait of a deep-sea fisher—and starts a train of events that makes of this short novel perhaps the most gripping tale yet to come from the author of “A Farewell to Arms” (Hemingway, “One Trip Across” 20). This introduction offensively dismisses Cuba as a “land of violence” without clarifying the nature and causes of that violence and misrepresents the thrust of Hemingway’s tale as merely a “gripping” adventure story. While unspecified violence and adventure are undoubtedly interesting, the editor’s emphasis on them misdirects readers as they enter the story. These elements are certainly less important to the story than the brutal deaths of three young Cuban men who were fighting against a tyrannical government or the murder of a human trafficker.1

What is Cuban in this story? I could answer briefly: a few places, some foods and beverages, certain characters, and specific events that portray a moment in Cuba’s history and politics—a sort of backdrop created with brushstrokes of local color. But is that all?

The story begins with an impressionistic description of a spot near the Havana docks at sunrise. Since it is written in the first person, the narrator lends the reader his vision so that the reader can view it as if with his own eyes. The eyes move from the San Francisco dock, across the square with its fountain, to identify the surrounding buildings. Only the café, La Perla, is singled out and mentioned by name. The café’s full name is identical to that of the dock and the plaza. Cinematic objectivity gives way to remembrance when the narrator recalls the ice-wagons that have not yet made their rounds of the bars, an effective device to signal the early hour.

Next, Hemingway gives us another view of the city, this time from a sea vantage, suggested solely by naming landmark buildings: beyond the Morro Castle, the National Hotel and the Capitol, the tallest structures in the Havana skyline at the time.

The narrator, whom the reader already knows as the story’s main character, sails out of the harbor aboard his fishing boat, chartered to a wealthy client. They leave behind the hatcheries anchored in front of the Cabaña fortress and some skiffs by the Morro, heading into the Gulf Stream. The water is purple and full of eddies. They are about to catch a marlin with purple fins and a striped body; later, another huge black one. These details are included in a sequence that takes place in the afternoon.

At sundown, Hemingway again presents a postcard view of Havana: the Morro lighthouse, its beam cut short by the glare of the city; the dome of the Capitol, still visible. Later, in the story the narrator passes the lights of Rincón Baracoa, Bacuranao, and, finally, Cojímar, but only Bacuranao is described. Here, the narrator zooms in like a camera ready for a close-up, but the lens is a human eye that has not actually approached the object hidden in shadows; behind the eye, the mind remembers and supplies the details: “Bacuranao is a cove where there used to be a big dock for loading sand. There is a little river that comes in when the rains open the bar across the mouth. The northerners, in the winter, pile the sand up and close it. They used to go in with schooners and load guavas from the brook, and there used to be a town” (Hemingway, THHN 49).2 A hurricane swept the town away, though, and now nothing is left but a single shack, built out of debris from the ones the hurricane had destroyed.

The smell of sea grapes and the sweet aroma of the warm underbrush float out to the boat. It is late at night. The narrator cannot see the things that he describes or names, but they are there. Closer now, the reader sees—through the eyes of his host—a cheap Chinese restaurant where you can eat well for forty cents, and La Perla café, where a generous serving of black beans, beef, and potatoes, plus an Hatuey beer, cost only a quarter.

These details are absolutely accurate. Although they are only external—mere color, so to speak—they are indicators of an economic reality. The description does not portray the whole situation, but the “landscape” cannot be considered a superfluous element.

As soon as the first Cuban characters are introduced—no matter how seemingly insignificant—the true dimension of the setting becomes evident. The beggar drinking at the fountain and the out-of-work men sleeping against the buildings are more than brushstrokes of local color. They convey the poverty that existed in the underdeveloped and neocolonized country that was Cuba at that time.

Probably not everyone who reads the novel becomes aware of the significance of these two subtle elements built into the story’s setting. But the author knows what he has planted in the reader’s subconscious, and he has done so with the skill of a marksman.

When the main character runs into three young Cubans toward the beginning of the story, the rhythm accelerates, interest sharpens. The author gives no definitions or analyses. He brings the scene into focus, takes a snapshot, and records what his character sees and hears. These three young Cubans represent one side of a certain struggle.

Two other Cuban characters represent the opposite side of the same struggle. One of them is black and carries a Thompson submachine gun; the other—most likely white—wears a chauffeur’s duster and holds a sawed-off shotgun. They approach the scene in a closed car and open fire on the three young men, who are also armed and courageously fight back. But they fall, riddled with bullets. The scene is one of the clearest examples of Hemingway’s mastery of accurate description of detail with an economy of expressive means.

The blood splattered on the walls and the sidewalk is not local color; nor is the horse-drawn Tropical brewery wagon, behind which the last of the three Cubans standing takes cover as he shoots the man wearing the duster with his Lugar, mere decoration. These are realistic details carefully chosen for an aesthetic purpose.

The characters mentioned above are not the only Cubans in the story. There is a cunning, somber, black—very black—man who wears a string of blue Santería3 beads under his shirt, dark sunglasses, and an old straw hat. This man is an expert at baiting fishing hooks and charges one peso a day to procure and prepare bait. But what he most enjoys doing on board is sleeping and reading the newspaper. He apparently has no sympathy for any of the three Americans aboard the fishing boat (Harry Morgan, the owner; Eddy, the first mate; or Johnson, the wealthy client). There is a young man who rows, but he appears only once in the story. There are two Cubans who threaten Harry and some Galicians who, being an integral part of the island’s ethnic makeup, must also be considered Cuban characters. These are the men who drink, eat, and play dominoes at La Perla, and the ones who built the shack at Bacuranao, where they spend their Sundays. There is also a waiter at the café who never speaks.

In addition to the Cubans, there is Frankie, of undecided origin, who is deaf, drinks a lot, and always smiles. He appears deceptively stupid, but his expressive shortcomings might be the result of poor schooling, or might be a defense mechanism. There is also a little Spaniard who acts as a messenger in one of the scenes.

The remaining characters are American (Eddy, Mr. Johnson, and Donovan, the custom...