![]()

Part One

COMPETITION

The Pennsylvania & Virginia Frontier to 1758

![]()

One

Provinces Will Be Jealous of One Another

In the early 1740s, a Pennsylvania fur trader named Thomas Kinton observed a curious ritual during a visit to a Delaware Indian village near the intersection of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers. Kinton watched in amazement as the village’s inhabitants gathered around a rat that they had discovered lurking in their village. After some time, the Indians killed the unwelcome intruder. While the extermination of the rodent seemed commonplace enough to Kinton, the reaction of the Delawares to the rat’s presence in their village struck the trader as extraordinary. Many of the Indians “seemed concerned” over the appearance of the rat and its potential significance. These “antiants,” as the trader called them, approached Kinton and sternly informed him that “the French or English should not get that land [the Allegheny River basin] from them, the same prediction being made by their grandfathers on finding a rat on [the] Delaware [River] before the white people came there.” Kinton was confused as to why a rat should cause such alarm, but for the Delawares the presence of rats and bees, or “English flies,” as many eastern woodlands Indians referred to them, was a telling portent of impending troubles, as they were well-known products of the ecological changes wrought on the environment by the advancing tide of Euro-American settlement. It was a warning that trouble might be coming, and for these Delawares, many of whom were refugees from the eastern part of Pennsylvania, that was very unwelcome news.1

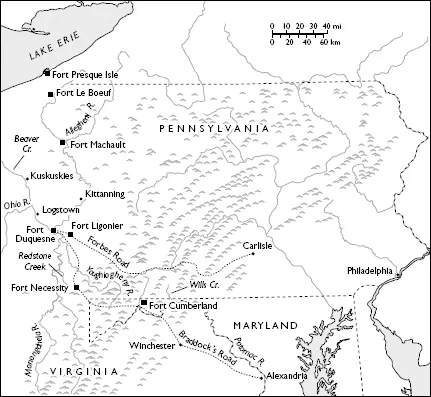

The Delawares had good reason to be concerned. In the decade preceding the start of the Seven Years’ War, often referred to as the French and Indian War in Pennsylvania, the hills and valleys of the western Pennsylvania frontier drew the interest of individuals, trading firms, colonies, and even empires. The focal point of this attention, the forks of the Ohio River, seemed destined to become a place of importance. At that point the south-flowing Allegheny River intersected with the Monongahela, gently moving in from the south, to form the westward rushing Ohio, gateway to the interior of midland North America. For centuries it had been a nexus of trade along a far-reaching network of native commerce, before being mostly abandoned at some point during the seventeenth century. But by the 1740s the forks of the Ohio and the Allegheny River watershed once more had become home to a multitude of Indian peoples. Many Delawares, Shawnees, and Mingos, a group of Iroquois peoples who were probably Senecas, moved west and south during the first half of the eighteenth century and settled alongside the numerous rivers and streams of the Allegheny–upper Ohio watershed. Most—and the Delawares in particular—were refugees from the mounting pressures for Indian land in the eastern portions of the American colonies and sought to assert their independence from the political and economic controls imposed on them by European empires or the Iroquois Confederacy, which claimed political dominion over the Indian peoples of the upper Ohio.2

These Indian migrants soon discovered, however, that they had not completely escaped the reach of Euro-Americans. French traders had been active in the Ohio Country since at least 1680, following Robert Chevelier de La Salle’s voyage of discovery down the Ohio River, and they had moved as far east as the Ohio forks in their pursuit of furs. Similarly, traders from the British colonies of New York and Pennsylvania followed migrating Indian peoples over the Appalachian Mountains and established lucrative trading posts along the western Pennsylvania frontier, before making substantial headway into the broader Ohio Country to the west. Indeed, the British traders soon outnumbered their French rivals, who lamented in 1730 that “the English are found scattered as far as the sea.” The role played by these peddlers, trappers, hunters, and adventurers, often lumped together under the generic name “Indian trader” transcends the economic boundaries of trade. They were the advance agents of westward Euro-American expansion. Through economic interaction with Indian peoples, traders made inroads into the trans-Appalachian west that led to diplomatic and political alliances while simultaneously heightening the awareness of their eastern colonial brethren to the latent possibilities of the region.3

By the 1740s, traders from Pennsylvania dominated much of the commercial exchange in the region. Replicating patterns of trade first established along the Susquehanna River in the early decades of the eighteenth century, Pennsylvania traders quickly established commercial ties with the Indian migrants who settled along the western Pennsylvania frontier. A report filed in 1732 with the Pennsylvania Assembly listed the names of at least twenty individuals who were engaged in trade with upper Ohio Indians. They plied their trade as individuals in free competition with one another, moving among the region’s many Indian towns, including Kittanning, Kiskiminetas, and Shannopin’s Town. The Pennsylvania traders transacted their business within a structured framework developed by William Penn, the colony’s founder. Penn required all trade with Indian peoples to adhere to the twin principles of fairness and equality. To this end, Penn instructed his colonists to “be tender of offending the Indians” and “let them know that you are come to sit down lovingly among them.” To prevent corruption and fraud, Penn disallowed corporate monopolization of the Indian trade. Trade was restricted to licensed individual traders who operated under strict parameters governing the type and price of all trade goods. Large firms or trading conglomerates were not allowed. To ensure adherence, the Pennsylvania government appointed supervisors to watch over the conduct of the colony’s traders and also to mediate conflicts between colonists and Indians. Operatives caught violating the regulations faced suspension or outright revocation of their trading license.4

For the most part, Penn hoped these restrictions would prevent traders from becoming land speculators. He believed that the lands granted to him by the king belonged first and foremost to their Indian inhabitants, and although his charter vested these lands in his name, Penn maintained that the land should be purchased from the Indians in an honorable and fair manner. He envisioned, perhaps naively, a system that would allow natives and settlers to “live together as neighbors and friends.” That rarely occurred, however, as Indians were pressured for their lands from the outset and were increasingly coerced into agreements where friendship with the colony depended on their submission to Penn’s designs. This dynamic illustrated an ulterior motive for Penn’s trade policies. The proprietor needed and expected to make a profit from land sales in his colony. Although he made exceptions when necessary, Penn had no intention of competing for Indian lands with private individuals, regardless of their role as traders or merchants. His trade restrictions prevented the organization of traders and merchants into business conglomerates that could challenge the proprietor’s monopoly over the land. Moreover, Penn enacted legislation that allowed only him or his heirs to obtain clear titles to Indian lands, which only the proprietor or his agents could then sell to colonists through the proprietary land office. He reserved the best land for himself as proprietary “manors,” a practice greatly expanded by his sons. Although Penn allowed tenancy on his lands to accommodate poor farmers, he opposed the sale of huge land tracts to private individuals. He feared that creation of a landed class in Pennsylvania would destabilize the colony, a concern perhaps influenced by the rebelliousness of landless frontier farmers in Virginia during Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676. Such social considerations were consistent with Penn’s vision of the colony as a “Peaceable Kingdom,” but they also ensured that Penn and his heirs would be the only land speculators in Pennsylvania. With no legal avenue by which to acquire large tracts of land, the elite in colonial Pennsylvania had little choice but to occupy themselves with commerce rather than land acquisition. Thus, as Penn intended, trade drove Pennsylvania’s public economy and charted much of the course of the colony’s relationship with the Indians, leaving land acquisition firmly in the hands of the Penn proprietorship and its agents.5

Penn’s regulations kept all trade and land initiatives under a fairly tight rein during the early years of the province. After Penn’s death in 1718, however, his system began to unravel. Penn’s heirs did not display his inclination for friendly interaction with Indians, nor did they exhibit the same restraint toward land acquisition. Thomas Penn in particular occupied himself more with expanding his family’s provincial holdings in Pennsylvania and selling land to incoming settlers than maintaining his father’s regulations. While he generally upheld restrictions on land purchases in order to maintain the proprietary land monopoly, Thomas Penn did not enforce his father’s trade guidelines. Regulation fell instead to the Quaker-dominated provincial Assembly, which became entrenched in a prolonged struggle for control of economic policy with merchants in Philadelphia and Lancaster. The large mercantile houses there encouraged unrestricted trade by supplying individual traders with goods on credit, which invariably led traders to amass large inventories that quickly outpaced Indian demand. As a result, hundreds of individually operating traders accumulated substantial debts to the merchant firms. Burdened by crushing debt, they ignored Pennsylvania’s commercial code and aggressively pursued increased profits by forming partnerships, ignoring price codes, swindling native consumers, and even operating outside the borders of the colony. Most of the acquired revenue went to pay off the merchant houses, which in turn extended larger lines of credit and recruited new traders, many of whom were unlicensed. Officials in New York, alarmed by the aggressiveness of these traders, asked the British government to regulate their activities if the Pennsylvania Assembly could not. Thomas Penn convinced the British colonial administration that such measures were unnecessary, but the complaint illustrates the inability of the Pennsylvania provincial government to enforce its policies. This weakness would have grave implications for Pennsylvania as the colony attempted to exercise authority over the Ohio forks.6

Fueled by merchants hungry for increasing profits, Pennsylvania traders secured control of the central region of the province and then transferred their activity to the western Pennsylvania frontier. Yet by the early 1740s the prospects for continued economic growth appeared bleak, primarily because the rich trade of the Ohio Country, the next avenue of expansion, flowed into French clearinghouses in Canada. French traders had long enjoyed control of the region’s commerce through a complex alliance system with the Indian nations of the Ohio Country. It was a formidable barrier against further Pennsylvania trade expansion, but one that weakened considerably in 1744 with the onset of King George’s War. The conflict, part of the long struggle between Britain and France for imperial dominance, provided Pennsylvania traders with an opportunity to erode French commercial dominion in the Ohio Country. The war disrupted the flow of French trade goods to the Ohio Country as military expenditures forced French officials to sharply curtail the Indian trade, and aggressive Pennsylvania traders, many of whom were Scots-Irish immigrants, quickly took over French trade networks in the eastern Ohio Country. To the delight of many Indian leaders, the Pennsylvania traders offered superior trade goods at a fraction of the price charged by the French. By war’s end in 1748, the Pennsylvanians had significantly cut into the Ohio Country market and established bases of operation in several Indian villages throughout the upper Ohio River watershed. Future commercial expansion into the west, and the wealth it entailed, seemed assured.7

There was perhaps no better example of the success that Pennsylvania’s individually operating traders enjoyed than George Croghan, an Irish–born trader who clawed his way to prominence during the 1740s and 1750s. Croghan’s personal trade network stretched throughout the Ohio Country, but he centered his activities near the forks of the Ohio River at Logstown, a mixed Indian community of Shawnees, Delawares, and Mingos. Croghan established storage buildings and council houses at the village, and from this supply and diplomatic center Croghan launched trade expeditions into the Ohio Country. The Indians brought Croghan and his contemporaries a myriad of animal pelts: primarily deer hides but also beaver, bear, moose, and fox. In exchange, the traders supplied the Indians with linens, metal utensils, cooking implements, and “powder, lead, [and] rifled-barreled guns.” The traders also maintained a large inventory of brass and silver jewelry and buckles, which Moravian missionary David Zeisberger claimed the Indians “considered as valuable as gold and with them they can purchase almost anything.” The favorable balance of trade filled the coffers of the merchant houses in the East and allowed roughhewn traders like Croghan to aspire to the trappings of wealth and the power that attended their newfound regional status.8

But the activities of Croghan and other Pennsylvania traders had unintended consequences. Attracted by the success of Pennsylvania’s Indian trade, other Euro-American interests began to focus their attention on the forks of the Ohio. Along the colonial frontier, where British authority was practically nonexistent before the 1760s, colonies often treated one another as competitors during periods of westward expansion. Overlapping land claims based on various colonial charters produced conflict as colonial governments, and the elites connected to them, competed with one another for land, trade, and Indian alliances. No colony would pose a greater challenge to Pennsylvania’s interests in the West than Virginia. For nearly half a century, much of the tension and strife that characterized the western Pennsylvania frontier involved the perceptions, expectations, and schemes of numerous Virginia private entrepreneurs, associated capitalists, and provincial officials who contended with their Pennsylvania counterparts first for control of the Ohio forks and, later, for the entire region. From the beginning, it was a competition for power in which economic elites and provincial officials from both colonies sought to impose their authority over the region and to control its resources. Trade with the region’s Indian inhabitants was an important stimulus of competition between agents of the two colonies, but land was the fundamental issue that divided those interested in the western Pennsylvania frontier. It was not simply physical control of territory or even ownership of specific tracts of land that mattered most but the power to dispose of the land in whatever manner the victor chose. Whoever made the decisions regarding the dispensation of lands not only would exercise authority in the region but also would control access to the region’s immense potential for income. Land, and the power to control it, lay at the heart of the struggle for authority along the western Pennsylvania frontier.

Like their Pennsylvania counterparts, Virginians’ interest in the western Pennsylvania frontier grew from developments within their own colony. During the early eighteenth century, Governor Alexander Spotswood of Virginia had taken an avid interest in the trans-Appalachian west, although his designs centered on land rather than commerce. Virginia’s early land policy had been based on the headright system, which promised fifty acres to anyone who emigrated to the colony and a bonus of fifty additional acres for every other person whose passage the original landholder paid. The system was designed to encourage the migration of farmers and tobacco producers, but wealthy investors manipulated the bonus clause of the plan to create an elite upper class of planter aristocrats who controlled vast tracts of land supported by a large population of landless tenants and black slaves. As Virginia expanded westward, the planter elite gobbled up huge chunks of frontier territory. The provincial government, dominated by the planters, supported, conducted, and fine-tuned this policy. In 1720, Governor Alexander Spotswood sponsored a new land policy favorable to speculators because it allowed qualified applicants to underwrite huge land purchases with little money up front. Under Spotswood, direct cultivation of the land became secondary to speculation, which promised fantastic profits once the land was surveyed and sold. Spotswood personally acquired more than 40,000 acres under this system, although his holdings were meager when compared to those of Thomas Fairfax, who by 1735 had gained title to more than 6 million acres of land in Virginia’s northern neck. By the Seven Years’ War, wealthy Virginia planters had become ardent speculators who routinely acquired titles to frontier land from the provincial government long before settlement of the lands in question got under way.9

It took little convincing to spur the Virginia planter aristocracy to action. As elites gained control over Virginia’s tidewater lands, aspiring speculators realized the future of land acquisition in Virginia lay beyond the Appalachian Mountains. Spotswood also recognized the potential value of the western region, but he understood that competition, both from other colonies and the French, would be keen. To secure Virginia’s interests in the region, Spotswood petitioned the British government in 1720 for permission to establish a military presence beyond the Appalachians. Intrigued by the prospect of undermining French influence in the Ohio Country, the Board of Trade, which regulated commerce and land in the American colonies, authorized Spotswood to tentatively move into the region. The governor’s designs quickly faltered, however, when competition among Virginians produced turmoil. Land speculators were major players in colonial westward expansion, but rivalry among speculators from the same colony often resulted in unrestrained competition for land that could produce unintended results. Spotswood’s program set off a frenzy among Virginia speculators, effectively blunting provincial efforts to establish a military presence in the Shenandoah Valley and instead producing confusion and chaos.10

Twenty years later, similar competitiveness marked Virginia’s efforts to expand along the western Pennsylvania frontier. In 1743, a trader and explorer named James Patton petitioned the Virginia government for a land grant at “the three branches of the Mississippi River [the Ohio forks].” The Virginia government initially refused Patton’s request due to mounting tensions between England and France but then reversed its decision after King George’s War broke out. In April 1745, the Virginia land office granted Patton a patent for 100,000 acres at the Ohio forks. Almost immediately other interested Virginians followed Patton’s example, including James Robinson, speaker of the House of Burgesses, who obtained title to an equivalently large tract of land adjacent to Patton’s. In addition to renewing competition among Virginia land speculators, their petitions also marked the beginning of an intercolony rivalry that would bring war, violence, and discord to the western Pennsylvania frontier region for the next fifty years.11

At the root of that competition was a struggle for authority. As the Seven Years’ War approached, both Pennsylvania and Virginia sought to impose their political authority over the forks of the Ohio. Officials in each colony believed that their charters gave them political jurisdiction over the region, but the Virginians were far more aggressive in asserting their claims prior to the Seven Years’ War. The foundation for their activity lay not only in Virginia’s charter but also its provincial government’s interpretation of the 1744 Treaty of Lancaster. The treaty conference had been called to address grievances among the Iroquois Confederacy and th...