![]()

CHAPTER ONE

SOCIALISTS

NATIONAL PERIODICALS IN THE HEARTLAND

Like feeding melting butter on the end of a hot awl to an infuriated wildcat.

OSCAR AMERINGER, If You Don’t Weaken

The moment Mother Jones stepped off the train and onto the station platform at Mt. Carbon, West Virginia, as she recalled, the “corporate dogs set up a howl.” The company town represented a new, industrial form of feudalism, erected by Tianawha Coal and Coke Company to house workers. Housing usually was substandard and company store goods overpriced. Officials kept a close eye on residents. Mt. Carbon was one stop among hundreds for the indomitable white-haired, bespectacled sexagenarian during decades of stumping and loudly supporting strikers in mining towns. Tianawha authorities warned Jones she courted arrest if she spoke publicly. She recalled, “I told him that the soil of Virginia had been stained with the blood of the men who marched with Washington and Lafayette to found a government where the right of free speech should always exist.”

1The company ordered the local hotel not to feed or house Jones. It evicted the mining family that offered her a night’s lodging and fired the husband. “Every rain storm pours through the roof of the corporation shacks and wets the miner and his family,” Jones reported. “They must enter the mine early every morning and work from ten to twelve hours a day amid the poisonous gases. As I look around and see the condition of these miners who produce the wealth of the nation, and the injustice practiced on these helpless people, I tremble for the future of a nation whose legislation legalizes such infamy.”2

Mother Jones’ vivid testimony in the International Socialist Review (ISR) departed from the intellectual debates that dominated the early years of the dense monthly launched in Chicago in 1900 by Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company, but by the end of the decade readers came to expect such tough reporting from the journal. By then the Review and the Appeal to Reason had emerged as the most significant nationally circulated socialist periodicals. By 1913, the Kansas-based weekly Appeal’s circulation rocketed to a stratospheric 760,000, making Julius A. Wayland’s newspaper Gulliver to the Lilliputian ISR’s 60,000 subscribers.3 But no socialist publishing venture made as much of an impact on American public discourse by publishing so much radical literature as did Kerr’s. This chapter will examine Kerr and Wayland’s considerable contributions to radical print culture. It will compare how the ISR and the Appeal adapted business and journalism strategies to perform social-movement media functions. Beyond those leading journals, the chapter surveys some of the hundreds of other socialist periodicals that ranged from a children’s magazine to union bulletins. Labor and politics emerge as predictably persistent topics, but more surprising themes such as religion, machines, and poetry thread through pages of the socialist press. First, a look at the similarities between ISR and the Appeal helps explain their leading role in nurturing socialist culture.

Commonalities between the International Socialist Review and the Appeal to Reason

Although ISR initially was as cerebral as the Appeal was folksy, the two periodicals had much in common. Their publishers did more than anyone to educate Americans about socialism.4 Wayland’s weekly claimed five thousand Appeal study clubs in 1906 that instructed readers in the social movement.5 Biographer Allen Ruff asserts Kerr’s successful business plan and commitment to making radical literature affordable and accessible made Kerr’s company “the foremost socialist publisher of the era.”6 Both the Appeal and ISR exerted much influence in Socialist Party politics, so much so that party leaders and socialist publishers eventually challenged their dominance of radical print culture.7 Crucially, both were independent periodicals with strong publishers and editors who did not have to answer to a party local or meddling press committee, as did many of their peers. Both publishers were products of the agrarian heartland yet succeeded in engaging readers in the urban East and mountainous West. Wayland and Kerr both experimented creatively with alternative business models to finance their anticapitalist ventures but resorted nonetheless to advertising. Their investigative reporting on labor issues and their activist journalism influenced radical politics in intended and unintended ways.

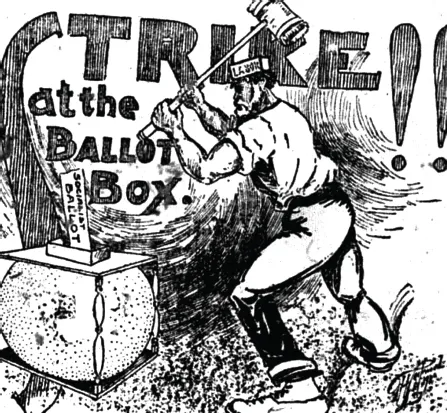

Untitled, Appeal to Reason, October 31, 1903.

The stature of the two journals also was partially the result of adding labor’s two most celebrated leaders to their mastheads. Eugene Debs penned editorials for the Appeal and mining organizer William “Big Bill” Haywood for the ISR. Another key to the two journals’ success was their prairie-bred publishers’ embrace of farmers as part of the proletariat, a departure from the European Marxists. Both publishers viewed advocacy journalism as the most effective way to promote socialism and counter hegemonic media. ISR, for example, once claimed the capitalist press “has held the workers in mental servitude for years, it has blinded us to our own interests.”8 Conversely, in 1911 prominent radical writer Joseph Cohen pronounced that the socialist press’s “opportunities for doing greater good are almost endless.”9 Kerr and Wayland both emphasized education as a prime function of the socialist press.

Kerr cast a broader and more intellectual net than the provincial Wayland. In its early years, ISR was a text-heavy sixty-four pages, plump with intellectually challenging essays and book reviews that kept its promise to report on international socialism, explain socialist theory, and relate socialism to American life.10 Ruff asserts the Review “conveys more information about the particular social and political cause for which it spoke than any other contemporary record.”11 It functioned as the voice of the movement’s theorists rather than of its rank and file, however, especially before 1908.

Kerr, yet another radical publisher inspired by Looking Backward, was the son of Scottish-born abolitionists who worked with African Americans in Georgia. Kerr discovered Marxism during studies with radical economist Richard Ely at the University of Wisconsin. He parlayed knowledge gained while working at a Unitarian publishing house after college into launching his own company in 1886.12 Months after marrying May Walden in 1892, the thirty-two-year-old publisher incorporated the Kerr company as a cooperative venture.13 When the Kerrs embraced socialism in the late 1890s, their lakeside Chicago suburban home became the nucleus of a circle of idealistic young socialists that included ISR cofounder and editor Algernon “Algie” Simons and his wife, May Wood Simons, who lived with the Kerrs for several months. May Kerr recalled how their enthusiasm for socialism “nearly set the house afire.”14

She also recalled her husband as a “shrewd bargainer.”15 The company translated and published innumerable European Marxist works, including the first English versions of the second and third volumes of Marx’s Das Capital. Its ambitious publishing program to make radical literature affordable and accessible introduced tens of thousands of Americans to a wide range of European radical thinkers, including the Brits William Morris and Robert Blatchford, Marx’s fellow Germans Friedrich Engels and Karl Kautsky, and Frenchman Paul Lafargue. Publication of these works made Kerr the main conduit of the transnationalism that colored American radical print culture.16

Kerr also Americanized socialism with its five-cent Pocket Library of Socialism series. Authors of the sixty pamphlets published in the company’s first decade-included Jack London, Clarence Darrow, and Debs.17 While the Appeal to Reason also published classic European Marxist works as well as those by Americans stretching back to Tom Paine, Wayland lacked Kerr’s enthusiasm for theory. In 1909, Kerr bought all plates and copyrights of the Appeal to Reason Publishing Company’s books.18 He also acquired copyrights from Debs and the Wilshire Book Company, the publishing arm of H. Gaylord Wilshire’s popular eponymous socialist magazine. Kerr’s expansive publishing ventures not only served as a repository and stimulus of socialist culture but also gave the ISR leverage against the circulation-colossus Appeal. The ISR’s debut in July 1900 further enhanced Chicago’s reputation as the hub of American radicalism.19 Because of its publisher’s broad swathe, no radical periodical performed the education function better than ISR.

The Launch of International Socialist Review under Editor Algie Simons

Kerr’s financing of the new monthly shows how socialist publishers adapted capitalist methods to fund their anticapitalist journals. Kerr initially sold two hundred $10 shares in ISR; Shareholders received no dividends but could buy books at cost.20 Kerr began to limit individuals to single shares and to allow them to buy these in $1 installments, a unique approach that dispersed control of the stock and enabled low-income workers to participate.21 By April 1901, some thirty-five hundred people subscribed to ISR at $1 a year, and an equal number bought it at newsstands for a dime. In a burst of corporate synergy, the magazine advertised Kerr books and pamphlets on its back cover and on inside pages. ISR also advertised other radical journals, which reciprocated.22 The company wobbled into the black by the end of 1903, although it continued to rely on personal loans and donations.

ISR followed the company model by publishing essays by every notable European socialist intellectual. Kerr and editor Simons also infused the publication with a distinctive American flavor. A Wisconsin farm boy who preferred reading, Simons escaped to the University of Wisconsin when a local lawyer gave him $100 to enroll. A product of the agrarian “hotbed of Populism,” whose family lost its farm in the Panic of 1893, Simons was receptive to socialism.23 Like Kerr, he read Marx in Ely’s class, and assisted him in the writing of Socialism and Social Reform. Simons also acquired some journalism chops by working as a stringer for the Madison Democrat and Chicago Record. His social conscience steered him to social work in Chicago in 1895, but fact-finding missions in the squalid stockyards’ “Packingtown” neighborhood convinced him only of charity’s futility. He joined the Socialist Labor Party and in spring 1899 began editing the SLP local’s Worker’s Call—which Kerr printed. Simons also stood among Socialist Party of America founders in Indianapolis. After the tragic death of the Simonses’ eighteen-month-old son, friends pooled funds to give the couple a respite in Europe, where visits with numerous socialist thinkers strengthened the Kerr firm’s transnational bonds. Once back in Chicago, Simons immersed himself in editing ISR.

Simons shared an ISR column with German-born socialist writer Ernest Untermann, titled “Socialism Abroad.” Readers found countless more international articles covering socialists from France to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, usually culled from European socialist magazines.24 Max Hayes compiled briefs in his “The World of Labor.” Essays scrutinized democracy and parsed socialism.25 ISR’s political contributors exploded any notion that radicalism spoke with a single voice. Simons raked anarchists, for example, in the wake of President William McKinley’s assassination by a self-described anarchist. Socialists use the ballot to end capitalism, he wrote, while useless anarchist violence enflames the public against all who advocate change. “Thus it comes about that over and over again the violent deeds of anarchists have been ...