![]()

1 |

Introduction to Vicksburg National Military Park |

President Abraham Lincoln called Vicksburg “the key” and believed that the war would not be won by the Union until that key was “in our pocket.” As the Civil War wore into its second and third years, Union efforts focused on capturing the heavily fortified citadel on the Mississippi River that prevented the Father of Waters from flowing, as Lincoln said, “unvexed to the sea” (fig. 1.1).

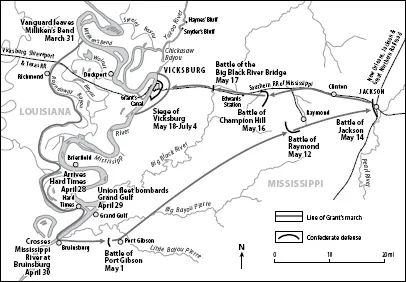

Fig. 1.1. Vicksburg Campaign Map showing Grant’s movements from March 31 to July 4, 1863

In May of 1863, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and about 45,000 soldiers—most from the Midwest—laid siege to the city and about 50,000 Confederate soldiers—most from the Deep South. After 47 days and combined casualties of 20,000, Gen. John C. Pemberton surrendered the city—on the same day that Gen. Robert E. Lee began his retreat from the Confederate defeat at Gettysburg. The war lasted another two years, but the Confederacy never surpassed its high-water mark on Cemetery Ridge at Gettysburg, and it never regained control of Vicksburg and the Mississippi River.

In the decade after Appomattox, survivors of the war—North and South—focused on healing their war wounds. The bodies of Union dead were systematically collected from shallow battlefield graves and re-interred in new national cemeteries like Vicksburg National Cemetery, the largest in the country with 17,000 burials. With no Confederate government to organize and fund reburial and commemoration of its fallen defenders, the Confederate dead were dependent on the charity of a defeated, demoralized, and economically devastated people. Consequently, white Southern women assumed responsibility for reburying the Confederate dead and raising monuments to their memory like that in Cedar Hill Cemetery (fig. 2.1).

By the twenty-fifth anniversary of the war, veterans had begun to raise markers and memorials along Union lines at Gettysburg that had been protected by a private preservation group. In the 1890s, battlefield preservation advocates established national military parks at Gettysburg (1895), Antietam (1890), Shiloh (1894), Chickamauga and Chattanooga (1890), and Vicksburg (1899). During the period of economic prosperity and national expansion between the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 and the U.S. entry into World War I in 1917, the states vied once again on Civil War battlefields, but this time the contest was about which state would honor its volunteer soldiers in the most effective manner.

At Vicksburg, Northern states led the way with impressive structures commemorating all the soldiers from their states who served at Vicksburg. Illinois (figs. 5.2, 5.3, 5.4) built a memorial resembling the ancient Roman Pantheon. Iowa constructed an elaborate exedra, an ancient Roman monument form shaped like a bench or seat, and ornamented it with an equestrian color bearer and six bronze relief sculptures depicting scenes from the campaign and siege (fig. 3.3). Most Northern state memorials were in place by World War I, but many Southern state memorials were not placed until the centennial of the war or later because of less abundant financial resources and a reluctance to mark a battlefield where the South had lost.

In 1903, Massachusetts became the first state to dedicate a monument—a heroic-scale bronze Volunteer (fig. 11.5) marching to war. The sculptor, Theo Alice Ruggles Kitson, was a native of Massachusetts and one of only three female members of the National Sculpture Society. Her mentor and husband, sculptor Henry Kitson, supervised placement of the memorial because she was home with their infant daughter, but she returned the favor a few years later when she made most of the equestrian color bearer for Henry’s Iowa Monument while he was ill. In addition to the Massachusetts and Iowa memorials, the Kitsons created 3 portrait figures, 24 portrait busts, and 54 portrait reliefs—many more than any of the other sculptors represented at Vicksburg.

The predominance of portrait memorials at Vicksburg results from the commemorative program orchestrated by the park commission that supervised the creation and operation of the park under the War Department until 1933, when responsibility for national military parks was transferred to the National Park Service. William T. Rigby, a Vicksburg veteran from Iowa who served as the resident commissioner from 1901 to 1928, effectively promoted the program of portraying each commander of a battery or brigade or larger group of soldiers. A total of 177 portrait figures, busts, and reliefs (fig. 1.2) line the park roads traversed each year by hundreds of thousands of visitors. The portraits, allegorical sculptures, and architectural monuments mark the battlefield and memorialize the men and events of the campaign and siege. They tell the history of the epic battle as well as the story of its survivors, who commemorated their comrades, fathers, sons, and brothers in imperishable granite and bronze.

Fig. 1.2. General Stevenson and the old VNMP Administration Building near the site of the Surrender Interview Marker

![]()

2 |

Overview of Memorial Art and Architecture at Vicksburg |

This book surveys the memorial art and architecture found in and around Vicksburg National Military Park (VNMP). The park preserves the battle lines encircling the northern and eastern perimeter of the Civil War–era city, plus a few outlying monuments and memorials dedicated to the 1862–63 campaign, siege, and eventual surrender of the Gibraltar of the Confederacy. During the heyday of commemorative efforts shortly after 1900, many local park boosters and countless park visitors recognized the effect of these memorials on the historic landscape. It was called the “Art Park of the South.”

The subject of most of this commemorative art is the courage and selfless devotion to duty of the 100,000 soldiers and sailors from 29 states who fought for months to control Vicksburg and the Mississippi River. The service and sacrifice of these men, approximately 20,000 of whom were killed, wounded, or went missing, was recognized during and immediately after the war with monuments in cemeteries and on courthouse lawns around the country like Vicksburg’s Monument to the Confederate Dead (fig. 2.1). Few monuments were erected at Vicksburg or other Civil War battlefields until decades passed and survivors gained historical distance from the horrific and heroic events of the war.

Fig. 2.1. Monument to the Confederate Dead, Cedar Hill Cemetery

By the 1890s, veterans realized that the sites of their martial exploits were being lost—in some cases to land development and in others to neglect. A movement began in earnest to protect and preserve important battlefields and to mark them with durable memorials. Union and Confederate veterans in Congress led efforts to appropriate funds to establish national military parks administered by the War Department at Vicksburg (1899), Gettysburg (1895), Shiloh (1894), Antietam (1890), and Chickamauga and Chattanooga (1890). As the fortieth and fiftieth anniversaries of the battles passed, aging warriors returned to the fields to pay homage to their fallen comrades, to their brothers in arms, and to their adversaries, whose courage and military prowess they respected. They journeyed back to Vicksburg and other battlefields to dedicate monuments and to commemorate the men and events of the war “without praise and without censure,” as national military park regulations required.

Many veterans participated in joint reunion encampments of Blue and Gray that became popular on the preserved battlefields. Those events not only reflected the reconciliation then occurring between North and South, they also facilitated it. And, as might be expected, the growing spirit of reconciliation and national reunification was memorialized in battlefield monuments like the Missouri Monument with its Spirit of the Republic (cover, frontispiece, fig. 2.2), a winged Nike or victory figure that wears a Phrygian bonnet like ancient Roman freed slaves, and carries a fasces, a bundle of rods symbolic of strength through unity, as well as an olive branch, which is emblematic of peace.

Fig. 2.2. Nike, Missouri Monument

The commemorative spirit of Civil War survivors and their families takes a variety of forms ranging from compact gravestones for the unknown dead to large memorials like the Missouri, Illinois (figs. 5.2, 5.3, 5.4), and Iowa (fig. 3.3) monuments, which are dedicated to all of the troops from an individual state. At Vicksburg, commanders of batteries, brigades, divisions, corps, and armies are depicted in reliefs and busts, as well as many full-length statues, including three equestrian portraits.

Patrons’ penchants for realism dictated that these effigies of specific individuals represent them accurately, especially in terms of physical appearance, uniforms, and equipment. Generic images of common soldiers such as those on the Wisconsin (fig. 3.4) and Mississippi (Driving Tour [DT]57) monuments were also expected to be anatomically correct and authentically equipped. Statues personifying Michigan (DT7, DT8), History (DT57), Peace (fig. 6.1), and other ideas are appropriately more generalized in appearance. Most of these allegorical figures are cloaked in voluminous gowns or flowing drapery suggestive of ancient Greek and Roman statuary, which was widely admired during the City Beautiful movement (1893–1917), when classical revival styles dominated public art and architecture and when most Civil War battlefield monuments were dedicated.

The story of these sculptural and architectural forms, their patronage, design, production, placement, and meaning illuminate the memorial art and architecture at Vicksburg, the commemorative art park of the South.

![]()

3 | The Art Park of the South |

Most of the memorials in VNMP were placed there during the two decades following establishment of the park by act of Congress in 1899. By the time the United States entered World War I in 1917 and popular interest shifted to soldiers of that war, hundreds of monuments and markers had been erected to memorialize the siege and defense of Vicksburg. Most of the monuments on the field today commemorate those who served at Vicksburg, but some, like the equestrian portrait of Gen. Lloyd Tilghman (fig. 3.1), who was killed at Champion Hill on May 16, 1863, recognize the service of soldiers who fell in the months of campaigning that culminated in the May 18–July 4 siege. A few memorials are dedicated to Gen. Joseph Johnston’s nearby Confederate Army of Relief, which had failed to aid Vicksburg’s defenders.

Fig. 3.1. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman Monument

Around the turn of the twentieth century, Civil War battlefields at Gettysburg, Shiloh, Antietam, Chickamauga and Chattanooga, and a few other sites were marked in a similar fashion. Gettysburg and Chickamauga and Chattanooga accumulated col...