![]()

1

Bread

and

games

In the annals of Western history, 1927 is not a spectacular year. Today’s historians do not consider it a significant turning point in any respect—not politically, economically, militarily, socially, or culturally. Perhaps only in the history of aeronautics could an event of the first magnitude be recorded in 1927: Charles A. Lindbergh’s first west-east crossing of the Atlantic in July.

The year 1927 cannot be compared to the year 1914, which initiated the end of an epoch, the Wilhelmian-Victorian age, and when “the lamps went out all over Europe.” Indeed there are some historians who see the first days of August 1914 as the end of the nineteenth century, rather than December 31, 1899. Nineteen twenty-seven also cannot be compared with the year 1929, which signifies for many people “Black Friday,” the beginning of the collapse of the New York Stock Exchange and the ensuing Great Depression and all its consequences. And most certainly 1927 cannot be measured with 1939—the outbreak of World War II, with all its profound and often horrendous effects on individuals and nations alike and the new power groupings in world politics.

Nineteen twenty-seven was relatively calm and uneventful. In German history—that is to say, in the history of the Weimar Republic—it was the time when one could hope for the gradual convalescence and strengthening of the “unloved republic.”1 The confused, chaotic, and often bloody beginning for the republic was in the past. It had become history. The transition from monarchy to a parliamentary democracy had been seemingly successful. The German people remembered very clearly the civil wars of 1918–19, the political assassinations, the Ruhr occupation, the catastrophic inflation of 1923, the various putsches from the extreme political Left and Right—but they were all memories. Things seemed better in 1927. The situation appeared to have stabilized, especially politically, economically, and culturally. There were enough indications to justify the friends of the republic speaking of a first flourishing of Weimar culture: in the previous year Germany had been asked to join the League of Nations in Geneva, thus ending the pariah status of the republic; the “Spirit of Locarno” seemed to prevail with the conclusion of a mutual security treaty between the two archenemies, Germany and France; the reparation demands of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles were being cut back and, piece by piece, eliminated. In literature, the arts, the theater, and the new film medium there was much adventurous mobility and an irrepressible drive to experiment. Expressionism, the German contribution to the development of modernism, became internationally recognized.

In this year, 1927, I was born. I am a member of Jahrgang 1927.2 It is the Jahrgang of the dickgewordenen Flakhelfer, “the antiaircraft gunners grown fat,” as we were called a few years ago in a rather acerbic German newspaper column. It is also the last “nonwhite” Jahrgang whose members had to pay with their health or with their lives for the insane “German war,” World War II. Too many in our “class” did not come back from this last big war. The “white Jahrgänge” are the age groups born in 1928 and thereafter.

On January 30, 1933, my Jahrgang was five or six years old. It was the day of Machtergreifung, “seizure of power,” the day on which the aging, second president of the republic, Paul von Hindenburg, entrusted the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP), Adolf Hitler, to form a new cabinet. It was the beginning of the Third Reich, which was supposed to last “a thousand years.” In reality it came to a catastrophic end after just twelve years. But in this short time in history, the Third Reich caused unspeakable suffering for the people of the world and brought about radical changes in the global constellation of power.

What do I remember of the years of my earliest childhood, of the time before the ominous date of January 30, 1933? There are three scenes that even today, more than fifty years later, are clearly etched in my memory like short but well-defined action clips from a movie. All three have a common denominator.

The first memory is a children’s scene. My childhood friend, Helmut D. and I were playing on a sandpile left over from minor road repairs made on our street. We flattened the sand and with small sticks drew figures and faces into the smooth surface. One was a swastika. We quickly looked around and then whispered to each other, “And now, when a Communist goes by, we will quickly draw four lines, and then it is a window.” Like this:

The implication of this seemingly banal children’s scene is not hard to detect. Even in the limited view of four-year-olds from the bourgeois milieu, Communists were threatening and somewhat sinister people. Our families were very middle class. Our fathers were pilots, former captains in the merchant marine who now had qualified as highly specialized navigational experts on specific and difficult navigable waters, which in Brunsbüttel, our hometown, meant the Elbe estuary, the approach to the Kiel Canal locks, and the canal itself. We lived in the Beamtenviertel, the civil servants’ quarter, which in our little town was considered a very desirable residential area. It was unthinkable that real Communists lived in our neighborhood. I cannot even remember neighbors who sympathized with the Social Democratic Party (SPD), the Sozis. Virtually all our friends and neighbors were World War I veterans who, because of their profession, had served in the Imperial Navy. Basically, my parents were apolitical. If I should classify them in modern political terminology, they probably stood slightly to the right of center. It stands to reason that their views strongly affected those of their children.

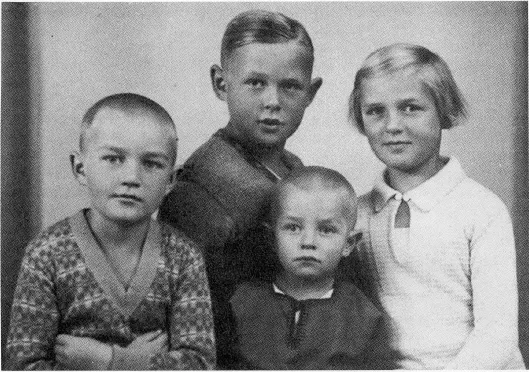

Portrait of my siblings and me ca. 1930. I was three years old. Left to right: Rudolf, Hans-Heinrich, Willy, Lieselotte.

The second scene is also only very short and fleeting. My mother and I were waiting at the ferry to cross the Kiel Canal, which divides our town in two parts, the north side and the south side. Brunsbüttel is by European standards a young town. It was built at the end of the nineteenth century as part of the gigantic construction project of the Kiel Canal, the link of the Baltic and the North Sea.

Aerial view of my hometown of Brunsbüttel. The estuary of the Elbe River, the canal locks, and part of the Kiel Canal are clearly visible.

As we were standing by the ferry gate, we heard from afar a strangely alien squeaking noise. When the band came closer the noise turned out to be the music of a Communist marching band approaching the ferry ramp. I can still see the twenty or thirty young musicians in their gray windbreakers, gray peaked caps, and red neckerchieves. What was so unusual about them was their music. It was a shawm band; its slightly nasal and shrill sound impressed me as very alien, almost exotic. Many years later, as a student of history, I learned why the political Left before and after the First World War revived the shawm, this obsolete and almost forgotten musical instrument from the late Middle Ages. It was a conscious gesture, a counterreaction to Prussian military music, the regimental bands playing their stirring military marches with their snare drums and big drums, their trumpets and trombones. This kind of music, with its sharply accentuated beat, I knew even as a five-year-old, and I loved the simple melodies and marching rhythms. With its mixture of wafting, lyrical, and at times shrill sounds, the Communist shawm band appeared to me not only different and strange, but also, in an undefinable manner, threatening. My mother must have had similar feelings, because she said when the ferry arrived, “Let’s go to the other side of the boat.”

The third memory of my earliest childhood has to do with the flag, the official colors of the republic. We lived in a relatively spacious six-room apartment, in one of the houses built in the civil servants’ quarter. The houses had been designed, financed, and constructed with federal money for the employees working on the widening of the Kiel Canal, a project finished in 1914. Each of the apartment houses had a tall flagpole in the front yard. It was customary at the time, and was probably recommended by the government, that on Sundays and on national holidays the national flag be flown in order to give the area a more festive appearance. I remember how happy I was when I was allowed to help my father or my older brother when it was our turn to fasten the flag to the rope and hoist it.

It is often pointed out in the relevant historical literature of the Weimar Republic that the initial insecurity and unpopularity of the first German republic is reflected in its controversial choice of the national colors. Many, but not all, of the responsible founding fathers wanted to show that they no longer identified with the Kaiser’s empire, the Second Reich. Instead of black-white-red, they selected the colors of the Jena Burschenschaft and the Lützow Jäger during the wars of liberation from the Napoleonic hegemony, 1812–15: black-red-gold.3 In 1848–49 the democratic and republican forces had attempted to create a progressive constitutional state and had gathered under this flag. But they failed. And when in 1870–71 the German unification came von oben—by governmental decree from the various German state cabinets, not by the efforts of the people—the new color combination of black-white-red was chosen: black and white, the old Prussian colors, plus red, the dominant color of the Hanseatic cities, representatives of the North German Alliance.

Black-red-gold were then the official national colors from 1919 to 1933. Nothing shows the feeling of inferiority of the “unloved republic” better than the merchant flag. The German merchant fleet sailed as before under the black-white-red flag with a black-red-gold Gösch, a small, hardly visible inset in the upper left corner of the flag.

As a five-year-old I did not know all this, but we children clearly felt how unpopular the republican flag was, at least in our part of town. Most people longed for the good old days, the splendor and pride of the imperial days and the old imperial colors, though in the historical sense they were not old at all. Black-white-red had been the colors for less than fifty years. In the early thirties we children spoke often of the black-red-gold national flag as “black-red-mustard,” and we were quite aware of the derisive connotation of this phrase.

The common denominator of these short memories of my early childhood is that they clearly show the deep-seated resentment and fear of the political Left harbored by the middle classes, of which we young children were representative members.

I do not remember much about the events of January 30, 1933, a day that changed the course of world history. My parents had purchased a good and rather expensive radio set, a small sensation for us children, and I seem to recollect endless broadcasts from Berlin, radio reporters who were close to tears with enthusiasm, the unending roar of approval of the masses in the capital, and, above all, the almost continuous strains of martial music and the hard, sharply accentuated rhythm of the marching columns celebrating their newly appointed chancellor with torchlight processions. But it is quite possible that my memory is playing tricks on me, for in the following years and decades I have seen and heard innumerable films and recordings of these parades and perhaps am projecting in reverse.

What I do remember very clearly, however, is an evening in our house in March 1933. My father, usually calm, sober, and levelheaded, came home very upset. My mother started crying. Neighbors and friends came and went. My father left again for a while. There was a mood of severe crisis. What had happened? Mr. H., a neighbor and friend of the family, chairman of the Pilots Brotherhood, their professional organization, had informed my father that he, Mr. H., had been forced to resign from his office. He was a member of the Deutsche Volkspartei, a moderate political party in the system that was no longer acceptable to the NSDAP in power. The National Socialists had gained 44 percent of the votes in the parliamentary elections of March 5, 1933. That was not the majority in the Reichstag, but they now had enough self-confidence to put pressure on all other parties and organizations in public life and force them to adjust to the new political realities and conform, “or else.” This “or else” meant, according to Mr. H., dismissal from the pilot profession, thus unemployment. The NS functionary had not been timid or squeamish in his conversation with Mr. H. Among other things, the man had said that he could well imagine that at least half of the pilots—there were about 110 to 115 at that time in our town—would be replaced by candidates sympathetic and true to the party line.

Unemployment was the fear and horror for millions of people of the industrial nations all over the world during the Great Depression. The real or potential loss of one’s job was felt by most people as an almost palpable threat. In later years I often heard my father proudly say that he had never in his whole life been unemployed, not for a single day, not even during the bad times immediately after the lost war. After four years of practically uninterrupted war service on submarines, he had come home. There were at that time thousands of sailors in every German port city who were laid up, who had no jobs and, what was worse, apparently had no chance for gainful employment in the foreseeable future, all because there were no ships. One of the decrees of the hated Treaty of Versailles was the confiscation of the entire German merchant fleet, all vessels above a certain tonnage, and delivery to the Allies.

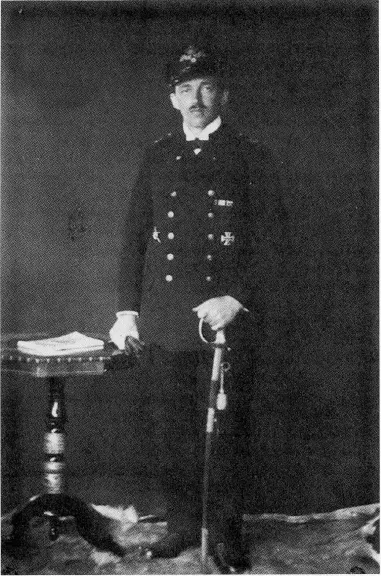

My father in 1918, a warrant officer in the Imperial Navy. He wears the Iron Cross First Class, right, and the Turkish Star, left, high decorations for his World War I service.

In these critical days, my father, without a moment’s hesitation, changed his profession. He either purchased or rented a small fishing boat together with his future brother-in-law, my Uncle Louis, and for the next two or three years he and my uncle earned their living as fishermen. The work ethic of his generation was very much intact, and he was proud of it.

Now, after he had succeeded through competence, connections, and probably some luck in achieving the dream profession of every sailor, that of pilot, he was faced with the very real threat of losing his job, of dismissal for political reasons beyond his control. He was almost forty-six years old and was married with four children, all still of school age.

Many years later, when I was an adult myself, he described the following scene to me: he had decided to join the NSDAP, to become a party member, in order to save his job. The highest party functionary in our town at that time was Mr. R. T., whom nobody had taken very seriously until then. He was the owner of a disreputable pub and he had gone bankrupt at least once. Mr. T., now Standartenführer T.,4 lived on the third floor of an apartment house on the Koogstrasse, the main street of our town. My father reported that he had climbed the stairs three times before he found the courage to ring the doorbell. Again and again he had said to himself in his beloved Low German language, Hein Schümann, dat kanns du doch nich mooken, “Hein Schümann, you can’t do that.” But he finally did do it and became a member of the NSDAP.

At that time my father probably knew little about the character and the aims of the NS party. I am certain that he had not read Hitler’s book Mein Kampf or the official party platform, the Parteiprogramm, with its twenty-five points. There were, however, certain themes of the new regime that continued to be proclaimed loudly and repeatedly and with which he wholeheartedly did agree. These were the sharp attacks on the Versailles treaty of 1919, which he and probably most Germans considered to be humiliating, dishonorable, discriminating, and unfair. (The harsh peace treaty of Brest-Litovsk of 1918, which was forced upon Russia by imperial Germany and which was often mentioned by the defenders of the Versailles treaty as a valid parallel, was virtually unknown.) My father was also angered by the Allied war and postwar propaganda. In particular he took quite personally the false and distorted presentation of the German submarine warfare, and the deliberate lies in connection with the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915 were examples he often mentioned.5

Why it was so difficult for my father to join the party and why he was later so ashamed of it, and remained ashamed to the end of his life, can be found in the style of the new state party, now also his party—their noisy and vulgar bragging, their lack of tolerance, the shady and questionable background of the new power elite on the local as well as the national level. The aforementioned Standartenführer R. T. is a ...