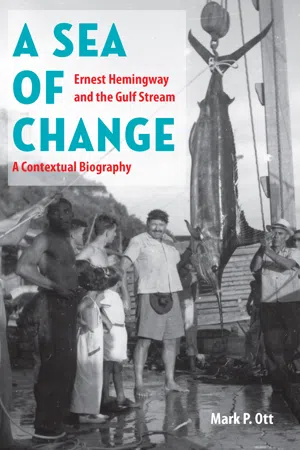

A Sea of Change

Ernest Hemingway and the Gulf Stream - a Contextual Biography

- 168 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

A fresh perspective on Hemingway's work

Early in his career, when To Have and Have Not was published, Ernest Hemingway's portrayal of themes, setting, and character was often compared to Cezanne's art - abstract. By contrast, in 1952, with the publication of The Old Man and the Sea, his style was described as comparable to Winslow Homer's - realistic.

At the center of this evolution is the contention that Hemingway's preoccupation with and scientific study of life in the Gulf Stream moved his theory and practice of writing away from the Paris art circle of the 1920s to the new realism of the 1950s. A Sea of Change explores the importance of Hemingway's relationship to the waters of the Gulf Stream that transformed his imaginative work.

Drawing primarily on Ernest Hemingway's handwritten and unpublished fishing logs and from published and unpublished correspondence and newspaper articles, Mark P. Ott structures this literary biography chronologically to tell the story of Hemingway's life as it becomes immersed in the Gulf Stream. Ott connects To Have and Have Not and

The Old Man and the Sea with Hemingway's philosophical and stylistic transformation as he became increasingly educated in the natural world.

A Sea of Change is the first study to examine Hemingway's complex relationship with the Gulf Stream and how it transformed his fiction.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

CHAPTER I

The Sea Change Part I

Days turned into weeks, weeks into months. Wives came and left; all taking their turns at the heavy rods.… Every day but a few they fished early and hard, keeping a running account: the log of the good ship Anita.… For two months, Hemingway’s intensity never lessened. His fishing partners came and left, but he continued unsated. Once, with that same intensity, he was married to trout fishing up in Michigan; then trout fishing gave way to the corrida. Now, with Death in the Afternoon in galley proofs, that ten-year passion is waning. These Gulf Stream days, pursuing fish as large as his imagination, are the beginning of a new pursuit which will last him the rest of his life. (1930s 92)

In the first place, the Gulf Stream and the other great ocean currents are the last wild country there is left. Once you are out of sight of land and of other boats you are more alone than you can ever be hunting and the sea is the same as it has been since before men ever went on it in boats. In a season fishing you will see it oily flat as the becalmed galleons saw it while they drifted to the westward; white-capped with a fresh breeze as they saw it running with the trades; and in high, rolling blue hills the tops blowing off them like snow as they were punished by it so that sometimes you will see three great hills of water with your fish jumping from the top of the farthest one and if you tried to make a turn with him without picking your chance, one of those breaking crests would roar down on you with a thousand tons of water and you would hunt no more elephants, Richard, my lad. (228–29)

America has always been a country of hunters and fishermen. As many people, probably, came to North America because there was good free hunting and fishing as ever came to make their fortunes. But plenty came who cared nothing about hunting, nothing about fishing, nothing about the woods, nor the prairies … nor the big lakes and small lakes, nor the sea coast, nor the sea, nor the mountains in summer and winter … nor when the geese fly in the night nor when the ducks come down before the autumn storms … nor about the timer that is gone … nor about a frozen country road … nor about leaves burning in fall, nor about any of these things that we have loved. Nor do they care about anything but the values they bought with them from the towns they lived in to the towns they live in now; nor do they think anyone else cares. ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1: The Sea Change Part I: The Anita Logs

- Chapter 2: The Sea Change Part II: The Pilar Log, the International Game Fish Association, and Marlin Theories

- Chapter 3: Hemingway’s Aesthetics: Cézanne and the “Last Wild Country”

- Chapter 4: Literary Naturalism on the Stream: To Have and Have Not

- Chapter 5: Illustrating the Iceberg: Winslow Homer and The Old Man and the Sea

- Appendix A: Chronology

- Appendix B: Selections from Hemingway’s Library

- Notes

- Works Consulted

- Index