![]()

PART ONE

Central European Origins

![]()

My Youth

I HAVE BEEN TOLD that I was born on January 4, 1871. There is no question that I was there, but I do not remember it. I was the last of fourteen children and an unexpected guest, so they had nowhere to lay me. The cradle had long since been put away; what could they do but bring in the big kneading trough and stow me in it, and because there were so many in the světnice (the large main room of the household) they shoved me under the bed to be out of the way. Obviously my late appearance on earth was none too welcome to my brothers and sisters. My oldest brother, Jacob, was already twenty-four and wanted to marry and take over the farm; and the other children probably figured that the more of us there were, the smaller the dowries would be. But before long the inborn kindness of our country people and a deep love for our mother made them forget their earlier reluctance to welcome me. They soon began to play with me, and I lived with my brothers and sisters in true family affection and concord.

Of us who were still among the living, there were ten eternally hungry children around the table, so I had plenty of nurses. When I grew older and began to understand what was going on around me, the other children taught me my name and the name of our village so that if I strayed off I could find my way home again. I learned to call our village Budyň. It completely satisfied me; for at that time I didn’t know any other place.

From my earliest childhood I herded geese. My mother gave me strict orders to pay attention and not stir from them so that chicken hawks and ravens wouldn’t carry them off. I was a faithful little gooseherd—not a single goose was ever lost. Our village in the district of Šumava lies in a valley enclosed by wooded hills. One stream runs from Kranicko, a second from Blsko, and a third from Pivkovice; all three joining like little brothers in our village square. When a drought struck us and the two smaller streams went dry, all the geese and ducks in the village gathered at the stream that flowed from Blsko. And it was there we boys used to bathe in a pool during the hot summer weather.

The family home of Frank J. Vlchek in Budyň, Bohemia.

I was no better than the rest of the boys. If they stole fruit from our garden, I combed other people’s trees, and we stalked the prince’s quail together, for the resident nobleman always enjoyed exclusive game privileges in the district. (In Bohemia, I might explain, there are three classes of country people—the landowners [sedlák], who own extensive tracts of land and some cattle; the cottagers [chalupník], who own a small plot of ground and a modest amount of livestock; and lastly, the tenants [domkář], who rent and are the poorest of all.)

My father was a landowner, and he was all goodness. I never heard him swear, he was never angry, and as far as I can remember, he never punished me or my brothers and sisters. Mother made up for it, but the more I felt her sharpness the more I loved her. I no longer remember what horrible thing I did, but I know that once I had as punishment to kneel on dried peas while I prayed my rosary aloud.

I went to school in Blsko. My first teacher was called Rybák (Fisher), and he well deserved his name. He no sooner dismissed us from school than he took his tackle and was off fishing. He knew every pool and deep hole in the stream; he knew what kind of fish lurked there and what bait to use. Many a time he walked with us boys as far as our village.

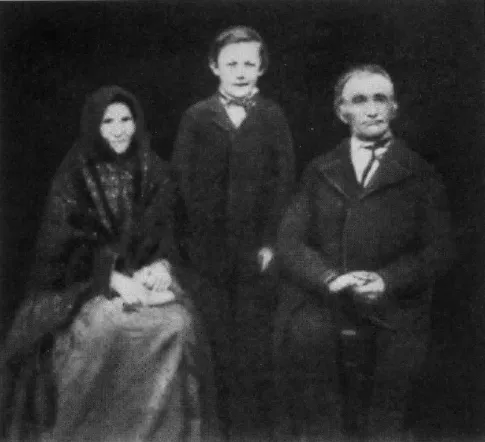

The parents Anna and Jan Vlchek with ten-year-old son Frank.

My second teacher was the old head schoolmaster, Fric. He was fond of us children and we of him, but most of all he loved a good pinch of snuff. Once he sneezed with such force that his wig tumbled off and we boys were so astounded that we even forgot to call out the usual courtesy, “God bless you.”

My third teacher was Vandas of Vodňany, a handsome young fellow who I have been told often spoke to my mother on my behalf, urging her to let me study, saying that I might make something of myself, but nothing has ever come of it. For a very short time I had as a teacher the newly appointed head schoolmaster, Vlček, an enthusiastic patriot who tried fervently to stir up our country people.

This sketch of my childhood would be incomplete without an account of the surroundings in which I lived and that greatly influenced my character and future. The various people we encounter naturally help to shape our character and determine the spiritual foundations of our being. In some communities there is nothing but disagreement and quarrelling, but it was not so in ours. The people were all industrious; they bore with one another and helped each other.

In our village there was a miller whose mill stood on a stream. The mill-pond was so small that he could only grind after a heavy rainfall. I often used to see him walking around his pond looking up at the clouds to see if it was getting ready to rain. He wore leather breeches though they had long been out of style. When his neighbors asked, “Well, Pantáta [Father], what kind of weather is it going to be?” He would answer, “Something’s going to happen.” So when it rained, he boasted, “See, what did I tell you?” And when it was fine he would also say that he’d guessed right. He prided himself not a little on this. Once when his wife complained to him about their stupid daughter, he said, “I don’t know whom that girl of ours takes after; a clever father, a wise mother, and the daughter such a dunce.”

Another inhabitant of our village, old Vondrys, was the self-appointed village philosopher. I used to listen to him. He herded geese with old Kohout. I can’t imagine Kohout without his pipe; he always had it in his toothless mouth, and to keep it from slipping out, he had a shoestring wound around the stem. He didn’t even take it out of his mouth when he was talking, so no one ever understood what he said. Once while they were herding, old Vondrys complained to Kohout, “That’s how it goes, Kohout. When we were little we herded geese, and now that we’ve grown old, we’re herding them again.”

AS SOON AS I grew up a little, I used to drive the cows to pasture, so early that the dew was still sparkling in the meadows. But no sooner did the sun mount higher in the sky than I hurried home with them so that I could get to school on time, as it was a quarter of an hour’s walk from home. After school I had to go to pasture again with the cows and drive them home only after sunset. A farmer in those days knew nothing about the eight-hour day; he toiled from dawn until dark. So even from childhood I was accustomed to work from sun-up until late at night, and I am still, thanks be to God, healthy and active enough.

Our pasture was not far from the slope where I had my sliding place. I used to take fresh cow dung and scatter it along the slope. Heel-less wooden shoes were made for sliding—how I used to fly. To be sure, it often happened that my feet slipped from under me, and I had a forced ride on that place where the back loses its dignified name. It wasn’t long before my breeches rubbed through. My mother could hardly patch fast enough to keep up, and at last she got tired of such endless tailoring. She took an old felt hat and divided it in two, sewing a half on each trouser leg behind. I didn’t like it a bit, but nothing was to be done, so I held my peace.

Once I was walking through the village with the halves of the hat puffing out behind me like balloons. Unluckily for me, Josef Vondrys, the village wit, was walking behind me, and when he saw my strange adornments he began to chant:

The chimney sweeper has a spot

The wife of the sweeper has it not.

Because he cleans the chimney, the sweeper needs it

But Frankie Vlček not a bit

His derisive song made me so angry that I ran straight home, stripped off the unhappy trousers, and threw them into the cesspool. I’d rather not tell what I got for it. Mother made me some new trousers of rough homespun, and since our people don’t wear fine batiste underwear, my body from the waist down smarted as if I had been whipped with nettles. Mother, good soul, soon took pity on me and bought me other trousers, but those homespun ones hung for a long time in the attic as a warning.

Even before I was ten years old, Mother used to take me with her to fairs in Vodňany, Písek, Netolice, Strakonice, Husinec, and Volyně so that I soon became familiar with all the villages and hamlets in our district. There used to be fairs in Vodňany every Tuesday. Once my mother ordered me to take our goat to the fair there and sell it. Probably she wanted me to have an early lesson in the farming business. I myself was filled with joy to think that she would trust me with such an errand. I tied the goat to a long rope, threw the loop across my shoulder, and set out for Vodňany. I had been instructed not to sell the goat for less than three florins, but all along the way I cherished the thought that I could get as much as four florins for her. I could demand a high price, then lower it later if necessary. Young as I was, I knew that our people haggled for every gratzer [equivalent to an Austrian penny]. While I was pondering this we reached the forest of Koráz around which the river Blanice winds, spanned by a black painted bridge. As we went down to the river, the goat got frightened of the bridge and would go no further. She planted her feet firmly upon the ground, and, try as I might, I couldn’t budge her from the spot. I didn’t know what to do, but at that moment a prominent farmer of the neighborhood came by with his cart and allowed me to fasten my goat on behind to force her forward. But the obstinate creature dropped to the ground and bleated grievously as though she were being flayed alive. I pitied her when I saw her dragged along the road, her hide rubbed off, and the rope choking her. I begged the farmer to stop, saying that I would try it again alone. I untied the goat, stroked her hard bristling back and examined her tenderly to see if any harm had been done. At last, two cottagers came by and helped me to carry the goat over the fatal bridge. She had bleated before, but now she actually shrieked in desperation. But as soon as she was safely over the bridge she yielded to her fate and we went on together through the thick wood toward Vodňany.

We were already near the town when a butcher came walking toward us. I had learned from my mother that when the buyers came out to meet the sellers one could be sure that there was a great demand at the market, and prices could be raised. “Well, my boy,” said the butcher, “what will you take for the goat?” I said that I didn’t know, that my mother was coming right behind me, and that she would set the price herself, but the butcher offered me four florins. My heart leapt with joy at the thought that I would be getting a whole florin more than I had expected, but I couldn’t resist trying my luck. “I’ll let you have her for five,” I said. The butcher stared. “Whoever heard of giving five florins for a goat?” he grumbled, but I noticed that he was looking her over carefully. All the same, I was a little afraid of losing a buyer so I said, “I’ll give you the goat for four florins and fifty gratzers, but you’ll have to give me three sausages into the bargain.” At the same time, I stretched out my hand as I had seen my elders do. The butcher seized it and the bargain was struck. I led the goat into his yard where he paid me and gave me the three fresh sausages agreed upon. When I was going cheerfully on my way past the tavern, I saw my mother and brother Josef approaching in the wagon. As soon as my brother saw me carrying the sausages, he burst out laughing and said to Mother: “I knew he’d sell that goat for any price before we got here.” Mother jumped down from the wagon and asked: “My son, how much did you get for the goat? Tell me the truth.” While she said this she gazed at me so searchingly with her forget-me-not blue eyes that she must have seen into my very soul. I told her the truth and also confessed that I had wanted to keep a florin since I had made such a good sale because I needed paper, a pencil box, and some other things for school. Mother stroked my head and said that she would buy me everything herself. I divided the sausages with them fairly, and mother kept her promise. She bought me all that I needed for school and a beautiful prayer book besides. I cherish it to this day.

People said that our house was three hundred years old. The walls were about three feet thick, and the windows were protected by iron bars no weaker than those that the big gaol [jail] in Prague boasts; no one could have broken through them. The village boys used to walk under our windows and talk with my sisters, and not for anything would they have betrayed each other’s evening flirtations. But my little bed stood in the same room, and I might have told our mother that the girls stood at the windows too long, so they used to silence me by giving me a few gratzers now and then.

When my sisters came to marry, I lost another source of income: there was no longer anyone to deliver hnětýnkas to after the harvest celebration. Every partner who had stood with my sisters in the circle at this time—and whom they thought worthy of the attention—received a hnětýnka from them the next day. This was a lavishly decorated cake resting on a plate and carefully wrapped in a starched kerchief whose corners stuck proudly out toward the four corners of the compass. I carried one in each hand, stretching my arms out so that the corners would not be crushed on the way. Sometimes it took me a whole hour, and I didn’t dare sit down by the side of the road, for the kerchief might have become soiled and my sisters would have noticed it instantly. When I finally arrived, my arms would be almost paralyzed, but that did not matter; all along the way I solaced myself with the thought of the good tip that would be my reward. The boys were usually grateful, but when some pinchpenny gave me only twenty gratzers, I had a good mind to hand it back. But I was never hasty. I used to deliver as many as fifteen of these hnětýnkas. But after two of my sisters married and one left for America, only Anežka (Agnes) was left, and she never went to dances. So the hnětýnkas stopped and so did my revenue.

Mother was a thrifty soul. Whenever she gave me a well-worn twenty-gratzer piece at fair time, she always admonished me sternly not to spend it all. I well remember going to a fair in Kestřany where two of my aunts lived. I had a lot of cousins in that village, and they were all buying gingerbread hearts, hussars, and marzipan and presenting them to one another. Of course I couldn’t buy much with my single coin and this troubled me. I was actually ashamed. After all, I was a landowner’s son and they were only cottagers. When I got home from the fair I complained bitterly but Mother turned on me with the sharp words: “You little spendthrift, you. Are you beginning already? It’s easy to spend money, but try to make it. Just look at the poor tenants in the village. They toil and moil on the prince’s estate and earn only twenty-five gratzers. And you want to spend when you aren’t making anything?” Mother’s stern but kind rebuke silenced me and I no longer complained.

Now and then my brother Josef slipped a coin into my hand, and sometimes when I kissed my godfather’s hand it meant a four-gratzer piece or so for me. That didn’t amount to much, but I had yet another secret source of income. We village boys poached on the prince’s preserves and went to Vodňany to sell the quail we had bagged. And once in a while I went to work and cut sugar beets for twenty gratzers a day and then hoarded my money carefully to be able to buy a ticket when a band of players came to town. They used to rehearse their rope walking and other acrobatic feats in our barn above the hay. But I wanted to buy a ticket and see the performance in the town square like the grown-ups.

![]()

Family Partings

THEN CAME A sad chapter in our lives when the close family ties were broken, and one after another the members of our family left home—some to get married and go to neighboring towns, others to travel even further perhaps never to return. Such partings are burials of the living, and I experienced many such burials at home.

The first painful separation in our family took place when my sister Anna left for America. She had always helped my brother Josef with the farm work as best she could since he could not tend to all of it himself; she performed the hardest manual labor both at home and in the fields; she was my brother’s right-hand man. I remember that we were threshing rye in the barn when Anna suddenly said to my sister Marie: “Mařenka (Molly), have you ever thought what the future holds for us? If we get married, it will probably only be to cottagers; the cottagers marry tenants, and from there the way is short to the beggar’s staff. Everything here goes from tens to fives; I can see no help coming from anywhere. I’ve heard that things are different in America. People go there poor and become rich. I’ve thought about it a lot. What would you think of trying our luck there, too?”

The plan appealed to Marie, and there on the threshing floor they made their decision. They began to get ready for the journey, but Marie changed her mind; she did not want to go to a strange country so far across the ocean. Anna, however, was firm.

One evening I was sitting with my sister on a bench by the table watching Mother in the dooryard.

“Anna,” I asked, “How can you go so far away from our mother? Suppose you never see her again.”

“There’ll come a time when every one of us will have to leave home,” my sister answered. “And you, little chick, will go away just as I am going. I have two strong, willing hands and a good head. I shan’t get lost out in the world.” With such assurance she was getting ready for her distant journey.

The day before her departure to America, my sister Katerina came with her four-year-old son Josef to say goodbye. She lived in a cottage in Zátava near Písek, a village three hours away from ours. Other relatives and friends also came to say goodbye. The day she left our parents wept as they went about their work; it was a sad parting. Outside in the yard stood a team of horses that Anna herself had often driven, ready now to take her on her final journey from our home to the railway station. A new black trunk looking li...