![]()

EARLY AKRON’S

INDUSTRIAL VALLEY

Akron is on the Continental Divide. Rain falling on the north side of town flows north into the St. Lawrence watershed. Rain landing in south Akron goes south into the Mississippi basin. You can actually see the water dividing and flowing both ways at the point where the Portage Lakes feeder enters the Ohio & Erie Canal across from Young’s Tavern on Manchester Road in south Akron. Water flowing to the left goes north through downtown Akron and Cuyahoga Falls into the Cuyahoga River and out into Lake Erie, from which it runs northeast through Lake Ontario, up the St. Lawrence River, and out into the North Atlantic Ocean. Water going to the right flows south into the Tuscarawas River and from there finds its way down to the Ohio River, a tributary of the Mississippi, which then carries it another 600 miles south and out into the Gulf of Mexico. Akron sits at the top of the ridge dividing the two continental watersheds—at the summit.

The barrier was well known to Native Americans long before Europeans arrived in North America. For hundreds of years Woodland Indians traveling south on the Cuyahoga River from Lake Erie lifted their canoes out of the water at Old Portage, carrying them up over the summit (from which Summit County takes its name) along 9 miles of the Portage Path before descending to the Tuscarawas River to continue their journey.

The north side of the Akron summit is much steeper than the south side. It is so steep, in fact, that when Ohio’s landmark Canal Act was passed in February 1825, canal engineers discovered that they would have to build sixteen locks to raise canal boats 149 feet in this last mile of the 38-mile trip from Cleveland, creating a staircase of locks. (This is why canal boats from the north often spent the night in the basin below Lock 15 before beginning the tortuous ascent, loading up on food and supplies in the morning after the Mustill Store opened.)

But what engineers viewed as an obstacle, Dr. Eliakim Crosby of Middlebury seized on as an entrepreneurial opportunity. He recognized that terrain this steep could be used to generate massive amounts of waterpower if an ample supply of water could be found. (Canal water couldn’t be used since it was needed to operate the cascade of locks.) But Crosby conceived a bold plan that would ultimately transform the site below Lock 5 into a dynamic industrial valley rivaling sites in England created by the Industrial Revolution.

Within a decade after Crosby implemented his plan, the valley came alive with several flour mills, a woolen mill, a furniture factory, five iron furnaces, and a distillery. The same water flowed out of one factory and into the next one, and all of them were powered by gravity. The site is preserved today from Lock 10 through Lock 16 as Akron’s Cascade Locks Park, developed by the Cascade Locks Park Association and operated by Metro Parks, Serving Summit County in cooperation with the City of Akron.

…

Eliakim Crosby arrived in Middlebury about 1820. Born in Litchfield, Connecticut, in 1779, he was well educated and taught school until he was twenty-seven years old, when, in 1806, he moved to Buffalo and studied medicine. After completing his internship, he settled in Simco, Ontario, where he opened a medical practice and married Marcia Beemer in 1810. But when the British invaded the United States during the War of 1812 and Crosby entered the U.S. Army as a surgeon, the British confiscated his Canadian property, which forced him to return to the United States.

Dr. Crosby continued to practice medicine after arriving in Middlebury, a village bordering the Little Cuyahoga River along today’s Case Avenue north of East Market. The ambitious doctor built a small iron furnace on the river in Middlebury. Since his medical practice was limited to a handful of families, he was exploring other sources of income. Running a major canal through his hometown, where he already had a business, would invite prosperity. Because Middlebury was on one of several possible canal routes over the Continental Divide, Crosby and other community activists lobbied for the canal.

But General Simon Perkins of Warren, a surveyor and an agent for the Connecticut Land Company, had other ideas. In addition to representing the land company, Perkins was privately speculating in land. Using state records, he acquired a substantial amount of property simply by paying modest amounts of past-due taxes on the land. He had, in fact, by 1825, amassed 1,003 acres at a total cost of $4.07. Perkins’s properties were located 2 miles west of Middlebury, adjacent to property owned by settler Paul Williams, in an area that would become downtown Akron.

Akron did not exist when the Canal Act was passed in 1825. Northeast Ohio was still a wilderness. In all of Ohio there were fewer than 300,000 people, about the population of greater Akron today. In what is now the Akron area there were only three settlers. As Henry Howe explains in his Historical Collections of Ohio, “In 1811, Paul Williams, Amos and Miner Spicer came from New London, Connecticut, and settled in the vicinity of Akron, at which time there was no other white settlement between here and Sandusky.” In fact, one of the objectives of Ohio’s Canal Act was to encourage the settlement of the northeastern part of the state.

Perkins persuaded Williams to combine their properties and lay out a town, one comprised of 172 acres, the majority owned by Perkins. When they registered it in the county seat of Ravenna, they called their town Akron, derived from a Greek word meaning “high.” In a skillful political move, Perkins had the town plat drawn with a canal running through the center of the village. And to clinch the deal, he deeded a third of the town lots to the state. This, together with Perkins’s vigorous lobbying in Columbus, was irresistible to the canal commissioners, who adopted the route through Akron.

Undaunted, Crosby, a clever politician as well as innovator, went to see Perkins, asking the general to partner with him on what Perkins first thought was a wildly ambitious scheme. Crosby proposed that they purchase water rights to the Little Cuyahoga River in Middlebury and build a diversion dam at the foot of Bank Street. From this dam they would “build a river,” a 2-mile-long millrace that would run west along the rim of the Little Cuyahoga Valley, turn south down what would later become Akron’s Main Street, and then go west down what would be called Mill Street, pouring its contents into the hydraulics of a gristmill that Crosby would build on the edge of the canal at Lock 5 (on the present site of the Radisson Hotel). After turning the machinery in Crosby’s mill, the effluent water (the tail race gushing from the mammoth mill) would flow down the precipitous slope becoming a new millrace running parallel to the canal (and through property that Perkins already owned). Crosby contended that this would attract other industries into the valley. But Perkins remained unconvinced, and it would take years for him to change his mind.

Meanwhile, work on the canal got under way. The Ohio & Erie Canal between Akron and Cleveland was dug by workers who had learned their trade building New York’s 174-mile Erie Canal. Running from Buffalo on Lake Erie to Albany on the Hudson River, the canal had opened in 1825 and was a resounding success. Having completed that waterway, which connected ports on Lake Erie with New York City and East Coast markets, these experienced workers migrated westward to build the Ohio & Erie Canal.

Working from dawn to dusk, thousands of men lining the Cuyahoga River Valley dug this first 38 miles of canal from Akron to Cleveland in less than two years. As described by historian George Knepper,

Some were local farmers who did the work in the off-season, but the majority were immigrant Irish and German workers….Poor, uneducated, and passionate, the Irish were often social outcasts ridiculed by “people of quality.” Yet it was their labor, often twelve hours a day in stinking ooze up to the waist, that built the canals. Thirty cents a day and a gill of whiskey was their usual wage until competition for their labor pushed wages up in the 1830s. Working conditions left them vulnerable to malaria, typhoid, and other scourges. Undernourished and overtired, living in squalor, they were an easy prey for epidemics such as a cholera epidemic of 1832 that killed hundreds. Alcohol, accidents, and murderous fights took many lives, and many a worker was placed in an unmarked grave along the ditch. Occasionally a worker, killed in mysterious circumstances, was buried in the canal bed. (Ohio and Its People, 154)

The “Ohio Canal,” as it was called, would be 309 miles long, running from Cleveland to Portsmouth, from Lake Erie to the Ohio River. Not a shortcut, it was to be an inland transportation system that would permit farmers (and, later, manufacturers) to ship their products to waiting markets on the East Coast by way of Lake Erie and the Erie Canal, or to settlements along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers from Cincinnati to St. Louis to the Port of New Orleans.

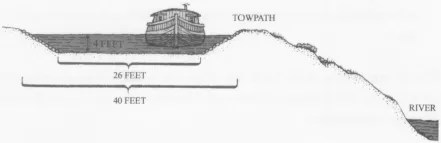

The canal was not merely a ditch. As specified by the canal engineers, the canal’s profile was to be a “prism” not less than 26 feet wide at the bottom, with sloping sides, to provide 40 feet of width at the water level, which was to be no less than 4 feet in depth. In practice, the canal was dug five to 12 feet deep, having a width that varied from 50 to 150 feet. To make them as waterproof as possible, the banks and bottom were lined with clay after grubbing and clearing the banks of any porous stone or vegetation that might contribute to leakage, which would lower the canal’s water level and cause boats to run aground.

Between Akron and Cleveland the canal mostly paralleled the Cuyahoga River, with a 10-foot towpath running between the two waterways. Together with stone masons and other artisans, the workers also built a total of forty-four locks to raise the boats 395 feet from the level of Lake Erie to the Akron Summit at Lock 1. Almost 40 percent of that rise would occur in the last mile, from Lock 16 to Lock 1.

The canal prism, or cross-section of the canal, as specified by canal engineers. (Drawn by the author and based on an illustration by Carl Sachs)

Launching such a mammoth project was a major happening, and the locals basked in the attention they received. People from as far as Columbus came to participate in the festivities. The Ravenna Western Courier and Western Public Advertiser sent a reporter to Akron’s Lock 3 on September 10, 1825, to cover the laying of the first lock stone on the Ohio & Erie Canal. He described the protracted ceremonies a week later under the headline, “Ohio Canal Celebration”:

The Ceremonies of laying the First Lock Stone of the Ohio Canal were more attractive and imposing than was generally anticipated—that so short a notice could have attracted such a concourse… . People from different and distant parts continued to assemble until 11 or 12 o’clock when the Middlebury Lodge, in connection with several visiting lodges, and many visiting brethren, together with a great number of Ladies, and a numerous collection of private citizens, were formed into a procession, and under the appointed Marshals, marched to the line of the Canal.

Mr. E. Torry, the Grand Marshal, ascended the Stone and delivered a short but emphatic address; an Ode was sung by a choir consisting of twenty-seven females and about an equal number of males, accompanied by instruments led by Adaph Whittlesey. The Rev. E. Williams then made an appropriate and impressive prayer; invoking the blessings of Heaven on the work and on all present—and imploring its prospering favors on the State and its great undertaking….

The stonemasons who built the Cascade Locks were commonly members of the Fraternal Order of Freemasonry, hence the formal Masonic ceremonies.

The Stone was then raised, and all who felt so disposed, deposited mementos underneath. During this part of the ceremony, the singers were performing an Ode … which had the most solemn and grand effect…. After the usual ceremony of the Cora, Wine & Oil and a benediction by the Grand Master, Dr. E. Crosby stepped upon the Stone and delivered an address which had been prepared for the occasion.

We were at too great a distance from the orator to hear distinctly … but we have been informed by those who did hear (and those in whose taste and judgment we have confidence) that its style was neat, and that its incidents were well selected.

The content of entrepreneur, politician, and salesman Dr. Eliakim Crosby’s speech was probably less important than Crosby making his presence known. After all, he had his eye on the future.

…

The dimensions of Lock 3 were the same as all of the others yet to be built. Designed to pass canal boats that were usually 70 to 80 feet long and 14 feet wide, locks were 90 feet long and 15 feet wide. The walls were built with huge rectangular blocks of cut sandstone, some weighing hundreds of pounds, and each was sawed by hand at one of several local stone quarries. It was a tight fit for some boats whose wooden fenders on the sides of the hull exceeded the 14-foot width specification. To protect the keel of the boats, the floor of each lock was lined with heavy wooden timbers. These can still be seen today on the bottom of some of the Cascade Locks. They remain well preserved underwater after nearly two centuries.

Locks were closed at each end by heavy wooden “whaler gates” (so called because they resembled the doors on whaling ships that were opened to drag whale carcasses aboard). Made of two plies of wood planks running at right angles to each other, these gates hung on wrought-iron hinges and closed in a V pointing upstream so that the “head” of water pressure against them could not push them open. Boatmen opened and closed them using heavy wooden handles called “balance beams,” or “sweeps,” that were eight to 9 feet long.

In raising (or lowering) a boat from one level to another, the locks operated like hydraulic elevators, but they worked entirely by gravity. Near the bottom of each gate was a wicket (also called a butterfly valve or paddle), which was opened and closed by means of an iron control lever that stuck up above the top of the gate. To lift a boat from one level to another, a boatman (or a lockmaster, though rarely in this part of Ohio) would first drain the lock by opening the wickets in the lower gates. When the water level i...