- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Teaching Hemingway and Modernism

About this book

Teaching Hemingway and Modernism presents concrete, intertextual models for using Hemingway's work effectively in various classroom settings, so students can understand the pertinent works, definitions, and types of avant-gardism that inflected his art. The fifteen teacher-scholars whose essays are included in the volume offer approaches that combine a focused individual treatment of Hemingway's writing with clear links to the modernist era and offer meaningful assignments, prompts, and teaching tools.

The essays and related appendices balance text, context, and classroom practice while considering a broad and student-based audience. The contributors address a variety of critically significant questions—among them:

How can we view and teach Hemingway's work along a spectrum of modernist avant-gardism?

How can we teach his stylistic minimalism both on its own and in conjunction with the more expansive styles of Joyce, Faulkner, Woolf, and other modernists?

What is postmodernist about an author so often discussed exclusively as a modernist, and how might we teach Hemingway's work vis-à-vis that of contemporary authors?

How can teachers bridge twentieth- and twentyfirst- century pedagogies for Hemingway studies and American literary studies in high school, undergraduate, and graduate settings? What role, if any, should new media play in the classroom?

Teaching Hemingway and Modernism is an indispensable tool for anyone teaching Hemingway, and it offers exciting and innovative approaches to understanding one of the most iconic authors of the modernist era.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Appendix A

Stylistic Consistencies Between Stein’s The Making of Americans and Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms

One whom some were certainly following was one who was completely charming. One whom some were certainly following was one who was charming. One whom some were following was one who was completely charming. One whom some were following was one who was certainly completely charming. … One whom some were certainly following and some were certainly following him, one whom some were certainly following was one certainly working. (104–5)

Nothing was changed in the town except that the young girls had grown up. But they lived in such a complicated world of already defined alliances and shifting feuds that Krebs did not feel the energy or the courage to break into it. … Most of them had their hair cut short. … They all wore sweaters and shirt waists with round Dutch collars. It was a pattern. He liked to look at them from the front porch as they walked on the other side of the street. He liked to watch them walking under the shade of the trees. He liked the round Dutch collars above their sweaters. He liked their silk stockings and flat shoes. He liked their bobbed hair and the way they walked. … He liked the girls that were walking along the other side of the street. He liked the look of them much better than the French girls or the German girls. But the world they were in was not the world he was in. He would like to have one of them. But it was not worth it. They were such a nice pattern. He liked the pattern. It was exciting. But he would not go through with all the talking. He did not want one badly enough. He liked to look at them all, though. It was not worth it. Not now when things were getting good again.

The good Anna had high ideals for canine chastity and discipline. The three regular dogs, the three that always lived with Anna, Peter and old Baby, and the fluffy little Rags, who was always jumping up into the air just to show that he was happy, together with the transients, the many stray ones that Anna always kept until she found them homes, were all under strict orders never to be bad with the other. … You see that Anna led an arduous and troubled life. (8)

Mr. and Mrs. Elliot tried very hard to have a baby. They tried as often as Mrs. Elliot could stand it. They tried in Boston after they were married and they tried coming over on the boat. They did not try very often on the boat because Mrs. Elliot was quite sick. She was sick and when she was sick she was sick as Southern women are sick. That is women from the Southern part of the United States. Like all Southern women Mrs. Elliot disintegrated very quickly under sea sickness, travelling at night, and getting up too early in the morning. (161)

Miss Charles was then one having general moral and special moral aspirations and general unmoral desires and ambitious and special unmoral ways of carrying them into realisation and there was never inside her any contradiction and this is very common in very many kinds of them of men and women and later in the living of Alfred Hersland there will be so very much discussion of this matter and now there will be a little explanation of the way it acts in the kind of men and women of which Miss Charles was one. (462)

I loved to take her hair down and she sat on the bed and kept very still, except suddenly she would dip down to kiss me while I was doing it, and I would take out the pins and lay them on the sheet and it would be loose and I would watch her while she kept very still and then take out the last two pins and it would all come down and she would drop her head and we would both be inside of it, and it was the feeling of inside a tent or behind a falls. (114)

Appendix B

Sample Assignments and In-Class Prompts

Appendix C

Hemingway and “the Code”

Appendix D

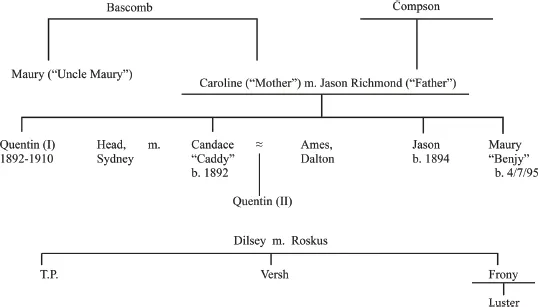

Chronology and Lineage, The Sound and the Fury

Appendix E

Discussion Questions and Writing Assignment

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Modernist Style, Identity Politics, and Trauma in Hemingway’s “Big Two-Hearted River” and Stein’s “Picasso”

- “Miss Stein Instructs”: Revisiting the Paris Apprenticeship of 1922

- Hemingway, Stevens, and the Meditative Poetry of “Extraordinary Actuality”

- Our Greatest American Modernists: Teaching Hemingway and Faulkner Together

- From Paris to Eatonville, Florida: Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises and Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God

- The Sun Also Rises and the “Stimulating Strangeness” of Paris

- Teaching the Avant-Garde Hemingway: Early Modernism in Paris

- Teaching Hemingway Beyond “The Lost Generation”: European Politics and American Modernism

- Twentieth-Century Titans: Orwell and Hemingway’s Convergence through Place and Time

- The Developing Modernism of Toomer, Hemingway, and Faulkner

- The Futurist Origins of Hemingway’s Modernism

- Hemingway, His Contemporaries, and the South Carolina Corps of Cadets: Exploring Veterans’ Inner Worlds

- Teaching Hemingway’s Modernism in Cultural Context: Helping Students Connect His Time to Ours

- On Teaching “Homage to Switzerland” as an Introduction to Postmodern Literature

- Chasing New Horizons: Considerations for Teaching Hemingway and Modernism in a Digital Age

- Appendixes

- Works Cited

- Selected Bibliography

- Contributors

- Index