![]()

CHAPTER 1

Representing Institutions

Asylums and Prisons in American Periodicals

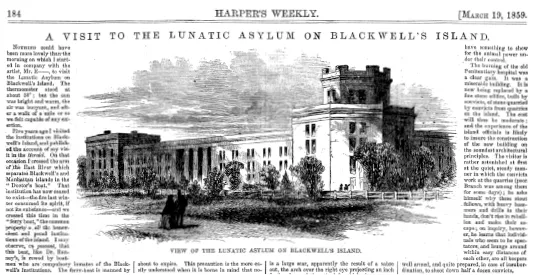

On March 19, 1859, Harper’s Monthly treated readers to a lengthy article, enriched with lushly detailed illustrations, depicting a journalist’s visit to the insane asylum on Blackwell’s Island, an engraving of which headed the piece (see fig. 2). The author of the piece, titled “A Visit to the Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell’s Island,” describes the inviting public grounds of the island, as well as the wards that house only mildly ill patients. But the author thirsts for more intriguing patients to view, and so, rejecting the superintending doctor’s recommendation to avoid these less savory inmates, the writer insists on a tour of the “maniac wards,” which contain the most unpredictable women.1 As the doctor unlocks the door to a room full of “furious female lunatics,” however, the journalist recalls “an account of an attack made by a furious maniac” in a Massachusetts institution, and he nervously surveys the patients gathered before him. “They were not pleasant to look at,” he reflects. “Some wore a sleepy aspect. Some looked venomously at us. A few resembled chimpanzees.” Nervousness aside, the tour proceeds calmly—at least until the journalist speaks, for then “the sound of my voice seemed to rouse them. I heard around me a buzz of strange croaking voices.” Gathering his courage, the writer turns his back to the room of animalistic maniacs and hastily pursues the doctor, who has moved into another part of the ward. Even as he departs, he seems to feel one patient’s “breath on the back on my neck” and expects “every instant to feel her claws there.” The journalist flees the scene, convinced that “nothing but the interposition of Providence would enable me to gain the end of the corridor without a death-grapple with some of them.” The Harper’s Monthly writer, one of many who penned stories about asylum visits during the nineteenth century, had cast himself into an almost literal lion’s den of insanity and lived to share it with an audience eager to stare, with horrified interest, at the beasts caged within the walls of the madhouse.

Figure 2. Some periodical articles about asylums included detailed illustrations, as did this engraving of the mental asylum on Blackwell’s Island. (Harper’s Weekly, March 19, 1859; author’s collection)

Articles about mental asylums, like that seen in Harper’s Monthly, were surprisingly frequent in nineteenth-century magazines and newspapers, as were similar pieces about prisons. Some took as their subject a general description of these institutions, dryly detailing factual information like location, construction, population, and methods of supervision and correction. Others offered more provoking glimpses at life within the institutions, and an intimate—often invasive—peep at the people living within. A survey of some of these journalistic asylum narratives and, more briefly, prison stories delineates how periodicals shaped readers’ understanding of insanity and criminality. The articles, in turn, contextualize how the newspaper women of this study approached the same subjects in authoring and authorizing their own tales. Building on the broader scaffolding of journalism’s rhetorical framing of asylums and prisons, readers can better understand how Fuller, Fern, Bly, and Jordan wrote within and, often, against other cultural representations of insanity and criminality.

READING AND REFORM

OF THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY ASYLUM

Fuller, Fern, Bly, and Jordan were not the only women who used sympathy in writing about public policies and institutions. Their narrative choices were consonant with other nineteenth-century women who found public voices through reform projects. Women used sympathy as a strategic tool to engage in public debates, and they did so primarily through the point of reform. Sympathetic expression was a hallmark of reform movements, including those involving prison and asylum conditions, a narrative stance that offered women a place in political discourse throughout the century. Debra Bernardi and Jill Bergman note that “benevolent activity” (and writing about that activity) “was one of the few professions available to women,” which, coincidentally, “grant[ed] them a voice in the public sphere”—the “domestic and moral nature” of reform work “allowed women to exercise a pronounced influence over the public sphere largely because the work was associated “with the feminized private sphere.”2 Women directed a highly gendered, emotion-driven attitude toward the subjects of their reform pieces as a tool for legitimizing their work. As I note in the introduction, the question of “separate spheres” of public and private influence for women and men is a complicated and contested issue in scholarship about nineteenth-century America. However, ideologically speaking and to varying degrees across the century, gendered assumptions tied emotional expression—including displays of sympathy—to femininity, and “the privatized realm of the home” functioned as “the site and source of feeling.” As Rosemarie Garland Thomson puts it, because sympathy signals “the affective bond that enables one to share another’s feelings,” women’s reform writing “became an arena where sympathy could be both manifested and mobilized toward achieving reform and empowering women.” Women used it, that is, to force public and political change. As such, sympathy “became the sentiment that legitimated” women’s “entrance into and appropriation of the public sphere.”3 From prison reform, asylum reform, temperance debates, and abolitionism in the antebellum period to suffrage, education, and immigration in the progressive era, women applied their concerns about social decline to a wide range of issues. In so doing, they deployed sympathy as a wedge to widen the scope of the masculinized “public sphere,” even as they stayed within proscribed gender roles.

Because “care for the indigent and sick was traditionally considered to be women’s work,” female reformers seized on asylums and prisons as “domestic spaces writ large,” especially since moral treatment, which I describe below, functioned within the model “of a well-regulated family,” living within institutional walls.4 In the hands of some writers, asylum rooms and prison cells became oddly domestic spaces, and advocates of reform “emphasized the domestic atmosphere of the asylum” in order to ensure and justify the authority of female voices in public affairs.5 Reformers realized that they could intervene with the governance of public institutions in the name of womanhood since they spoke “from a position of domestic, rather than overtly political, authority.”6 Unlike the bulk of articles about asylums and, in correlation, prisons—the vast majority of which were written by men—the articles that reform-minded newspaper women penned insisted on a fundamentally “feminine” way of viewing the people within these institutions. They modeled a sympathetic gaze, in contrast to the sensationalized and often dehumanizing gaze of other articles and stories, as exemplified by the Harper’s Weekly article that opens this chapter. In the process, they amplified their own professional voices, based, paradoxically, on gendered ideas about emotion that supposedly constrained them and undermined their ability to speak about public issues within male-dominated media.

Asylums and prisons offered almost ideal locations for women to enter public conversation, especially through journalism. I look here at asylums, in particular, to illustrate my point. The number of mental hospitals—or, as they were also called in nineteenth-century popular language, insane asylums, lunatic asylums, or madhouses—skyrocketed in the early to mid-nineteenth century. America had only 18 asylums in 1840; 121 more were built by 1880, and the number increased to 300 by the early twentieth century.7 The “typical” American asylum saw admission rise from 31 to 182 patients annually between 1820 and 1870 alone.8 Medical professionals and the general public debated the best methods of treatment such hospitals should offer—or if they should offer treatment at all, rather than simple “warehousing”—especially in the early decades of the century, as reform efforts, spearheaded by progressive religious groups, gained traction. Beginning in the eighteenth century, English (and, later, American) Quakers, especially, championed “moral treatment” in both madhouses and prisons, calling “first and foremost to appeal to and sustain the patient’s essential humanity.”9

In the early nineteenth century, moral treatment was a preferred method at the Blackwell’s Island asylum, which opened in 1839 as New York’s premier mental hospital. As Samantha Boardman and George Makari explain, the asylum “was designed to be a state-of-the-art institution” that emphasized the human, rather than bestial, qualities of the mad; the need for a semblance of normalcy, such as the omission of prisonlike bars on windows, regular clothing, and what we would now recognize as occupational therapy; and the categorization and separation of patients based on type of illness. Dr. John McDonald, one of the hospital’s designers, differentiated between “the noisy, destructive, and violent,” “the idiots,” “the convalescents,” and “those in the first stages of convalescence and such incurables [who] are harmless and not possessed of bad habits.”10 An 1866 visitor to Blackwell’s Island described this philosophy of care in action: “The main treatment on which reliance is placed for cure consists in sedatives and tonics, the freedom from active excitements, and the establishment of correct habits. As happiness or unhappiness in all depends upon mental training, so whatever tends to establish an evenness of temper aids not only in preventing insanity, but in actually restoring the diseased mind to its normal condition.”11

However, public faith in asylum reform and moral treatment diminished as the century wore on and doctors failed to cure a growing population of asylum patients—and, not coincidentally, as the cost of housing patients likewise grew. David Rothman describes a “decline from rehabilitation to custodianship”—paralleled in philosophies about the treatment of criminals, as well.12 Although the phrase “insane asylum” provoked negative reactions across the century, depictions grew even more pejorative in the 1880s and 1890s.13

As illustrated by print culture, Americans had always taken interest—for better or for worse—in public institutions. Articles about Blackwell’s Island, the Tombs, Bellevue Hospital, New York police courts, and other asylums and correctional facilities abound in both popular and reform-oriented newspapers and magazines of the nineteenth century. Additionally, scores of fictional works depict madness and crime, often exploring fears about being wrongfully confined in asylums and prisons, a source of real horror for readers, judging by the popularity of this theme. Opinions among the general public, however, were not always in keeping with those of reform-minded individuals. Even during the period of moral treatment and positive reform movements early in the century, American readers consumed a steady diet of periodical stories that equated mental illness with violence, alongside stories about women who went insane when forsaken by lovers. Even a few of the countless, sensationalistic headlines—“An Insane Convict’s Bloody Work,” “Maniac Runs Amuck,” “A Maniac’s Deeds of Blood,” “Strangled by a Maniac”—suggest the spectacular nature of such articles.14 All too frequently, mad and bad characters served as little more than sources of superficial entertainment, opportunities to gawk at unfortunate people. Indeed, Reiss characterizes nineteenth-century psychiatry as “something of a spectator sport,” and madhouses, as well as prisons, became “prominent tourist attractions … [v]isited by those who merely wanted to gawk at the poor, the insane, and the criminal.”15 Although the idea of “asylum tourism” began much earlier in Europe—most famously with citizens paying to tour London’s notorious Bethlem Hospital (Bedlam)—some American institutions, as well, found easy sources of income in the practice. Beginning with the first asylum in colonial America, visitors could “come and gape at patients as if they were animals in a zoo,” though some superintendents charged entrance fees in an attempt “to discourage such visits.”16 Blooming-dale Asylum superintendent Pliny Earle, for one, spoke out against the demeaning practice: “Why should [people] visit asylums for the insane, with no higher purpose than to be amused at the freaks of an idiot or the ravings of a madman … ?”17

Nevertheless, evidence of its public appeal appears frequently in American periodicals. W. H. Davenport refers in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, for instance, to the “sight-seer[s]” and “visitors” and “ordinary pleasure-seeker[s]” who travel to the island for general tours.18 In fact, by the antebellum period, the practice of visiting prisons, asylums, and other institutions was well enough established that New York guidebooks and periodical articles provided detailed information about how the curious could secure tours.19 Visitors might plan a delightful outing and even bring “picnic lunches to [the] verdant grounds” of places like Blackwell’s Island.20 One journalist explained, “Visitors are usually eager to know the cause of this or that case of insanity, and pleasure undoubtedly would be conferred by the gratification of their curiosity. Romance upon romance lies in the past of the unfortunate patients.”21 Day-trippers could satisfy their own imaginative impulses by inspecting a cast of colorful characters and constructing a plot for the helpless objects of the visitors’ gaze. Americans took the desire to visit asylums with them when they traveled abroad, and they sent home accounts of asylums in other countries, which were then printed in newspapers. Likewise, European visitors to America toured asylums, most famously Alexis de Tocqueville, Charles Dickens, and Harriet Martineau.

Periodical pieces, both fictional and non-fictional, often follow a readily recognizable formula in describing asylum visits. The writer first departs for an excursion to the asylum with ...