![]()

PART ONE

EDITOR’S

INTRODUCTION

![]()

WILLIAM SMITH, THE AUTHOR

William Smith (Fig. 1), the author of Expedition, was born April 20, 1727, at Slains, a small village north of Aberdeen on the coast of northeastern Scotland, to a family of small landholders. Following his enrollment in the local parish school, the young pupil, reportedly through the auspices of the Society for the Education of Parochial Schoolmasters, began instruction in 1735 preparatory to matriculation at King’s College, Aberdeen, as a scholarship student, whose residency was supported by an endowment. Smith attended King’s for four years, finishing his studies there in 1747. Two of his biographers, Albert Frank Gegenheimer and Thomas Firth Jones, could not confirm if Smith received an MA diploma. A frequent practice at universities in both Scotland and England was for students to finish their studies without officially receiving their degrees, but Robert Lawson-Peebles has suggested that while Smith’s name is not found in the incomplete King’s College records, the young man may have been awarded his MA degree later when he was in a financial position to afford it. In either case, Lawson-Peebles has noted that the documents germane to Smith’s later “Honorary Doctorate at Oxford clearly indicate that he possessed the degree.”1

Fig. 1. John Sartain after Benjamin West, The Reverend William Smith (1880). Benjamin West’s original portrait of William Smith was painted in 1757. (The Library Company of Philadelphia.)

For the next several years, Smith’s activities are not well documented. A letter, signed by him and printed in the October 1750 issue of The Scots Magazine, indicates that at age twenty-three he headed a committee of Scottish schoolmasters that petitioned Parliament to augment their salaries. The Scots Magazine for December reported that the youthful Smith, who must have been an impressive personality to be entrusted with such a task, departed Abernethy (near Perth), Scotland, for London in late 1750 to make the case directly to Parliament. Although unsuccessful, Smith’s labors were not completely in vain as they gave him invaluable public experience and the opportunity to make professional contacts, one of whom, Thomas Herring (1693–1757), as archbishop of Canterbury amid a court of senior clerics, would prove to be of great value to his aspirations and projects.2

Herring’s thinking must have influenced the impressionable Smith. As the archbishop of York at the opening of the Jacobite Rising in 1745, Herring promptly called for a vigorous resistance to the Stuart cause threatening the British throne. He advocated what Lawson-Peebles has referred to as “familialism,” emphasizing the idea of union by combining loyalty, liberty, comparative religious tolerance, and public tranquillity. In practice, union also embodied an action Herring applauded, the murderous suppression of Highlanders following the decisive government victory at Culloden in April 1746 by the English prince, William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland (1721–65), captain general of the British Army. Although many Anglicans in Scotland had supported the abortive rebellion, and the northeastern region of the country was receptive to Jacobism, Smith remained faithful to King George II (1683–1760). As a student, he witnessed considerable military activity and the spectacle of his college town changing hands several times. In 1751, Smith brought his certainty in Herring’s teachings, including a deep sense of British nationalism and destiny, across the Atlantic Ocean.3

A pivotal moment in Smith’s life was his acceptance of the position of tutor to the sons of Colonel Josiah Martin (1699–1778) of New York. Supported by a letter from the archbishop of Canterbury to his former student, New York Lieutenant Governor James DeLancey (1703–60), Smith departed London with the two adolescents in early March 1751 and reached New York on May Day. Although he would return to Britain three times in the future, Smith would establish his career and residence permanently in America.4

Residing in Rock Hall at Far Rockaway, the Martin family estate on Long Island, Smith authored an anonymous pamphlet consisting of twenty-seven pages of poetry accompanied by a lengthy introductory prose essay, entitled Indian Songs of Peace: With a Proposal, in a Prefatory Letter, for Erecting Indian Schools (New York, 1752); this tract also included “A Letter for Yariza, an Indian Maid.” For the first time, Smith evinced in print a deep concern for Native America, a subject that would appear frequently in his writings and culminate with publication of Expedition in 1765. Ann Uhry Abrams has suggested that he “pursued a peculiar kind of religious anthropology.” His body of work attests to the fact, she added, that Smith “was fascinated, if not obsessed, with the American Indians—their customs, habits, costumes, artifacts, and beliefs, especially concerning protection of their souls.” Thomas Firth Jones has argued that after only a short period in New York, however, the Scot could not have mastered “an Indian language, let alone an Indian perspective,” and that his “aboriginal position was a masquerade,” a mere literary device for Indian Songs of Peace. Whether or not Smith was learning a Native tongue, few Europeans or Americans could achieve a true “Indian perspective,” and while he could understand the indigenous peoples only on his own narrow, paternalistic terms, the young scholar’s keen interest in them was nevertheless real.5

Although classically educated, Smith, “reflecting the academic and political culture of Aberdeen,” was a progressive in teaching, who wrote A General Idea of the College of Mirania (New York, 1753), a copy of which he sent to Benjamin Franklin, a trustee of the Academy of Philadelphia. This utopian treatment advocated an institution embracing the particular needs of America, with emphasis on agriculture, history, and religion; further, the Scottish tutor suggested founding a separate school to instruct the “mechanic profession,” which would not require the study of ancient languages.6

For Mirania, Smith composed a prologue in verse, which included six lines on the subject of the Native peoples:

Lo! The wild Indian, soften’d by their song,

Emerging from his arbours, bounds along

The green Savannah, patient of the lore

Of dove-ey’d Wisdom, and is rude no more.

Hark! even his babes Messiah’s praise proclaim,

And fondly learn to lisp Jehovah’s name!

Smith prophesied that Native Americans were destined for radical and inevitable change, including a conversion to Protestantism; a transfer of loyalty from the French Crown to King George II; and, through growing contact, an acceptance of Anglo-American culture, renewed afresh in the forests. Only then could they be considered eligible for the Scot’s notion of the British “family.”7

Franklin and other trustees wanted to expand their existing academy and charitable school in Philadelphia and possibly to establish an institution of higher learning; consequently, Smith’s teaching precepts in Mirania interested them. Following a brief visit to the city in spring 1753, Smith, perhaps promised a teaching position or more by Franklin if he obtained the proper credentials, returned to Britain to receive the requisite holy orders and was ordained a deacon and priest of the Church of England in December. Sailing back to America in April 1754, the new clergyman was appointed a professor of natural philosophy at the Academy of Philadelphia.8

Smith had published another treatise on a Native subject, A Speech Against the Immoderate Use of Spirituous Liquors, Delivered by a Creek Indian, in a National Council, on the Breaking Out of a War, about the Year 1748 (New York, 1753). It originated with the New York secretary for Indian Affairs in Albany, Peter Wraxall (c.1719–59). Drafting an abridgement of Dutch and English documents, 1678–1751, relating to the Five (later the Six) Nations, or the Iroquois Confederacy, he chanced upon shorthand notes of “A Speech Against the Immoderate Use of Spirituous Liquors,” delivered by a Creek (Muscogee) to a “national council” at the start of a war around 1748. Wraxall, in 1752, gave a copy of this address to Smith, who thought it had “all the parts or members of the most perfect oration,” and he edited the text and arranged for its inclusion in the New York Gazette the following year. While in London for his ordination, Smith also organized a reprint, issued with three related pieces under one cover, the whole entitled The Speech of a Creek Indian … to Which Are Added, 1. A Letter from Yariza, an Indian Maid. 2. Indian Songs of Peace. 3. An American Fable; a second edition appeared later that year, again in the English capital, as Some Account of the North-American Indians; Their Genius, Characters, Customs, and Dispositions, towards the French and Indian Nations. As would prove to be Smith’s general practice, in none of the above works was any attribution to the author made.9

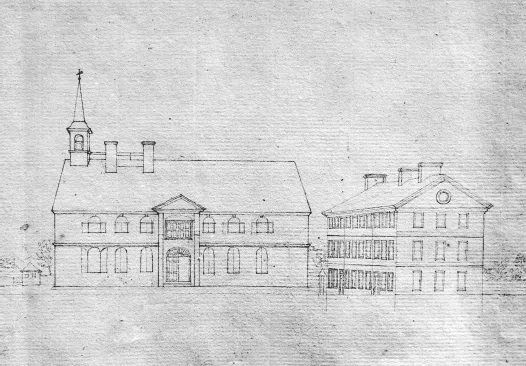

The charter of the Academy of Philadelphia was altered in late 1754 to permit the issuance of degrees. Smith was selected provost of the new college, Academy and Charitable School of Philadelphia (Fig. 2), the following year, and in 1756 he developed an innovative and sweeping curriculum, thus emerging as a leading scholar and cleric in colonial America. Emboldened by his position and status, the provost dared to enter politics as an avid supporter of the powerful Penn family and dominant proprietary party, and hence a rancorous adversary to the legislative Assembly dominated by the Society of Friends. Smith, without qualms or hesitation, soon stood as an opponent to Franklin, a Quaker ally.10

Fig. 2. Peter Eugène du Simitière, Fourth Street Campus, College of Philadelphia: Academy/College Building (built 1740) and Dormitory/Charity School (built 1762) (c.1770). This drawing depicts the Academy and College of Philadelphia (on the left) as Provost William Smith would have known it about five years after the publication of Expedition. (From the University Archives and Records Center, University of Pennsylvania.)

An ardent British patriot, Smith avidly followed the war with France that had begun in what is now southwestern Pennsylvania on May 28, 1754. Virginia Colonel George Washington (1732–99) and the regional Six Nations’ leader, Tanaghrisson or Tanacharison (fl.1700–54), jointly leading a mixed Virginia-Ohio Iroquois detachment, ambushed a small French diplomatic party and killed its emissary, Ensign Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville (1718–54). This minor skirmish at what is today Jumonville Glen, Pennsylvania, is credited with igniting the worldwide conflagration later known as the Seven Years’ War. Washington withdrew to a small, hastily constructed stockade, Fort Necessity (near what is now Farmington, Pennsylvania), only to surrender it to the French on July 4. Never reluctant to express an opinion, Smith denounced the colonel for capitulating to the French in a letter of July 18 to his Anglican friend and political ally, Reverend Richard Peters (c.1704–60). During the escalating crisis, Peters, as a commissioner with Franklin and others, had just attended an intercolonial conference convened at Albany, New York, to coordinate defensive measures and a treaty with the Six Nations, but the ensuing Albany Plan of Union was rejected or ignored. Contemplating the “fatal Blow” to British interests following Washington’s submission, Smith believed that by prematurely forcing a fight with an alert adversary of unknown strength, and by refusing to wait for reinforcements thought to be only a few days away, the Virginian was guilty of “Foolhardiness.”11

In the wake of Fort Necessity, Smith wrote ominously to Archbishop of Canterbury Herring in October 1754 that “the [Ohio] Indians are going over to the French.” In addition, the anxious Scottish cleric imagined the French enticing to the west the Pennsylvania Rhinelanders, some of whom were Roman Catholics and therefore in his mind disloyal. Regarding them as unable to distinguish between political systems, he feared that the French could take advantage of this presumed ignorance. To Smith, the only means to gain German loyalty was to send missionaries to their settlements. He urged the archbishop to influence the Anglican mission organization, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, to direct its efforts increasingly to Pennsylvania rather than to New England, where such activities might not be as necessary.12

Smith’s burgeoning martial ardor found expression in a pamphlet of forty-five pages entitled A Brief State of the Province of Pennsylvania. It was written as a letter that he composed anonymously and had printed in 1755 by Ralph Griffiths (c.1720–1803) in London. Smith sharply denounced the alleged inability of the Quaker-dominated Assembly to secure the borderlands against what would be termed the petite guerre (small war) of the French and Native warriors. This irregular, hit-and-run fighting, as practiced in the largely undefended and vulnerable Pennsylvan...