![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Idol Is Party

In October 1859, the beginning of Benjamin Dorr’s twenty-third year as rector of Philadelphia’s historic Christ Church, John Brown, five black men, and sixteen other white men, including two of Brown’s sons, attacked the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia). Although Brown failed to spark a slave rebellion that would raze the South in an Old Testament conflagration, Herman Melville would extol him as “the meteor” of the American Civil War: the militant abolitionist whose ignition of a long-simmering crisis threatened to rend the American nation and to explode the Reverend Dorr’s church.

Robert Tyler, a Philadelphia attorney, member of Christ Church, chairman of the Democratic State Central Committee, and eldest son of former President John Tyler, decried “Old Brown and his Confederates.” “By profession Negro and horse thieves,” he wrote, “they have stained their hands and souls with the most diabolical murders. They have violated all Law, Human and Divine.” People of the Southern states, he warned, “will establish a separate Confederacy in less than two years unless the people of our Section fall back from the atrocious doctrines now proclaimed by the [Republican] Opposition.”1

Contrarily, another member of “The Nation’s Church,” an up-and-coming young attorney and an associate of the Reverend Dorr’s son Will, praised the fiery old prophet of abolition. Joseph G. Rosengarten was passing by train though nearby Martinsburg when he heard news of the raid in progress and alighted for Harpers Ferry. Arrested by alarmed local militia, Rosengarten spent a night in jail in nearby Charlestown. Released the next morning by order of Virginia’s Governor Henry Wise, with whose son he was acquainted, Rosengarten proceeded to Harpers Ferry in the company of an artist dispatched by Harper’s magazine to cover the story. Seeing John Brown in custody, “[w]ounded, bleeding, haggard, and defeated,” Rosengarten later lauded the “noble” abolitionist as “the finest specimen of a man I ever saw.”2

The breach in the Reverend Dorr’s church between the likes of Joseph Rosengarten and Robert Tyler epitomized the autumnal crisis in the nation at large. Within weeks of his capture, Brown was tried and executed for treason. Almost six years later, serving then as a Union corps staff officer amid the aureole of victory in the civil war that Brown had delivered, Rosengarten would write:

[I]n the glorious campaigns of our own successful armies, I have never seen any life in death so grand as that of John Brown, and to me there is more than an idle refrain in the solemn chorus of our advancing hosts—‘John Brown’s body lies mouldering in the ground, As we go marching on!’3

Conspicuous among Southern sympathizers in Philadelphia stirred by Brown’s raid was another member of Dorr’s congregation: Kentucky-born John Christian Bullitt, scion of a Kentucky political dynasty who had moved to Philadelphia in 1849 and established himself among its leading attorneys. Although “educated in the political faith of the Whig Party, as promulgated by Henry Clay,” Bullitt’s opposition to “anti-slavery agitation,” as his obituaries later noted, led him “to abandon the faith he once held and attach himself to the Democratic party.” “At the time of the John Brown raid,” according to one account, “he was one of the members of the party who had no hesitation in assuring the South that Philadelphia had no sympathy with fanaticism.”4 In mid-January 1860, Bullitt and four hundred other prominent Philadelphians entertained Southern guests to a lavish dinner organized for the purpose of disavowing sympathy with Brown and repairing North-South relations.5

But Southerners seemed only to hear Northern abolitionists’ paeans to Brown, and it displeased Philadelphia diarist Sidney George Fisher, a conservative Whig, that “Southern politicians, for party purposes, industriously represent the whole North as banded against slavery and the South.” The truth of the matter, and the South’s “only safety,” Fisher observed, “lies in the fact, well known to every one here[,] that the great mass of the Northern people, are friendly to the South and are willing to support all its just and”—acknowledging slavery—“some of its unjust claims.”6 But, as Southern politicians persisted in yoking Northerners with abolitionists, despite most Northerners’ disavowals of Brown, and as they threatened to secede unless the federal government gave free rein to slavery’s expansion, Fisher’s diary entries took a significant turn. Although deprecating Brown as a “fanatic,” Fisher grew concerned that the “friends of slavery are attempting to destroy” the “cause of liberty, order and civil rights.” “Events are showing,” he wrote, that those “blessings” and the federal union “are incompatible” with slavery. “Which then shall we sacrifice?” he proposed. “Every right thinking, conservative man will answer—preserve all three if possible; if that be not possible, sacrifice slavery first.”7 Fisher, like significant others among the city’s elite in the deepening crisis, was moving closer to the anti-slavery views of Philadelphia’s most venerable living citizen.

Horace Binney, then eighty years of age, was “the Grand Old Man” of Philadelphia, esteemed foremost among the city’s citizens, as an historian notes, for his “professional prominence, devotion to city, extensive extracurricular participation, impeccable reputation, personal charm and physical handsomeness, the best social and, of course, family connections, an extreme but active senescence—and … lots of money.”8 A devout Episcopalian and a leader in the congregation of Christ Church, Binney was one of Benjamin Dorr’s closest confidants and godfather to Dorr’s eldest son, William.

“He is a great lawyer,” Fisher wrote of Binney, “and, except in a democracy, would have been a great statesman.”9 Binney had never made any secret of his loathing for the Democratic Party, a stance that had stymied his political prospects. Often proposed for a seat on the Supreme Court, Binney declined his only nomination by Whig President Zachary Taylor, knowing that his outspoken criticism of Democrats would have derailed his confirmation in a Senate controlled by that party.10 Fisher believed Binney’s scorn for Democrats a bit extreme, but he nonetheless admired the “old man,” confiding to his diary: “His influence has been, & still is, most beneficial and important. He is in fact an institution in Philada:, an oracle, universally respected, once indeed, it might have been said, universally obeyed.” Fisher perhaps knew Binney through Benjamin Dorr, who had officiated at Fisher’s marriage in 1851 to the sister of Charles Ingersoll, although Ingersoll and Binney, colleagues at the Philadelphia Bar, had become antagonists in the politics of the 1850s.11

Appointed a director of the First National Bank at only 26 years of age, Binney had been elected in 1832 to the U.S. House of Representatives, campaigning against Democratic President Andrew Jackson’s veto of legislation to extend the charter of the Second National Bank of the United States, centered in Philadelphia. To him, Jackson’s war on the bank exposed a ruinous spirit of political partisanship that he believed had overtaken the Democratic Party.12 In Binney’s judgment, the base fault of the Democratic Party, from Jackson’s time through the 1850s, was its willingness to stoop for power. The Democratic Party “is inseparable from the institution of slavery,” he opined in 1860 to Alexander Hamilton’s son. Binney viewed Northern Democrats as dupes to the demagoguery of Southern slaveholders who sought to make “The Democracy”—his sarcastic term for a party commandeered by meanly self-interested slave masters—a handmaiden to slavery’s expansion in the United States.13

Like the city at large, Philadelphia’s historic Christ Church found itself at the active epicenter in 1860 of two pressing national fronts: the old Mason-Dixon Line separating the slave states of the South from the free states of the North, and the racial divide separating blacks from whites while also dividing whites throughout the North. With parishioners on opposing sides of both of those increasingly stressed fault lines—Tyler versus Rosengarten, Ingersoll and Bullitt versus Binney—all eyes and ears turned then to their rector. Which side was he on?

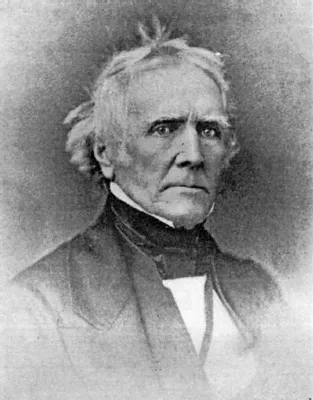

Horace Binney (Owen Wister, “The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania,” The Green Bag 58, 60 [1891].)

In July of 1836, Philadelphians and the country at large mourned the passing of William White, the cleric who had presided over the separation of the Protestant Episcopal Church of the United States from the mother Church of England, who had served as chaplain to the revolutionary Continental Congress and to the new government of the United States located in Philadelphia, and who had officiated at the state funeral in 1799 of George Washington.

The funeral for Bishop White “had been surpassed in Philadelphia only by that of [Benjamin] Franklin,” with stores closed for the day and more than 20,000 mourners of all religious denominations as well as the mayor and city council turning out to pay their respects to the clergyman revered as one of the nation’s Founders. For fifty-eight years White had been rector of Christ Church, Philadelphia, which had come to regard itself as “The Nation’s Church” for its historical role in the Revolution and in the founding of the United States. The assistant minister, John James Waller, stepped up as rector, but Waller fell ill and died within a month of White’s death, and suddenly Christ Church had to cast about for someone to succeed the venerable bishop.14

The church chose Benjamin Dorr, age forty-one, who since 1835 had been directing all of the Episcopal Church’s domestic missionary activities. Born and raised in Salisbury, Massachusetts, at the mouth of the Merrimack River about forty miles north of Boston, Dorr proudly traced his ancestry to the earliest English Puritans who settled New England: Philemon Dalton on his mother’s side, who with wife and five-year-old son came in 1635 to Dedham and eventually settled in Ipswich; and, on his father’s side, Edward Dorr, who emigrated from England to Boston in 1670, married there, and settled in Roxbury. Benjamin Dorr was the fifth son and seventh child of Edward Dorr’s great-grandson, also named Edward Dorr, who had volunteered three years as a soldier in the Revolution before settling in Salisbury to raise his family.

After his graduation from Dartmouth College in 1817, Benjamin Dorr moved to Troy, New York, to apprentice in the law office of Amasa Paine, one of the most eminent members of the New York bar. In his second year of law study, according to attorney John William Wallace, Dorr changed course, leaving the legal field, “where the laborers are many and the harvest not worth taking away,” for a more “glorious expanse, where the laborers are few and the harvest is great.” Dorr entered the General Theological Seminary of the Episcopal Church just then opened in New York, one of six who comprised the seminary’s first class. “Henceforth,” Wallace wrote, “he dedicates himself to holier ends.” Ordained a deacon in 1820 and a minister in 1823, each time by John Henry Hobart, bishop of New York, Dorr began his ministry in the United Churches of Lansingburgh and Waterford, near Troy. In the summer of 1822, at twenty-six, seeking to restore his health, which had “given way in consequence perhaps from too great devotion to study and to pastoral duty,” Dorr set off on an overland journey of four months through the western frontier.15

Traveling mostly by horseback, Dorr wended through the Indian reservations of western New York, exclaiming at the fruits of Bishop Hobart’s efforts to make Christians of the natives. “Here,” he wrote upon his visit to Oneida Village, “a spot [near Utica] which once echoed only to the wild War-Whoop of the savage … I saw their little church, with its spire pointing to that heaven where HE resides, ‘who hath made of one blood all the nations of the earth!’” To Dorr, Hobart’s mission echoed the apostle Paul’s call for a universal church of people from all nations.16

Dorr traversed Lake Erie by boat as far west as Cleveland, then rode on horseback to the westernmost extent of his travels at Sandusky, Ohio. Carrying the recommendation of Bishop Hobart and other New Yorkers of some professional and political eminence, the young minister was welcomed in Columbus by Philander Chase, Bishop of Ohio, whose ministry impressed him for its pioneering rusticity. The bishop himself, as Dorr wrote, was “reduced to the necessity of tilling the ground for the support of his family,” yet Dorr delighted in fishing the trout streams, setting off “early in the morning to shoot wild turkeys,” and hunting primeval forests teeming with deer, pheasants, and squirrels.17

“Having visited the ancient and most curious Indian mounds at Centreville,” Dorr crossed the Ohio River into Kentucky and headed for Lexington, where he found “a civilization and a society worthy of a part of ancient Virginia. Here he was most kindly received and entertained by Mr. Clay, even then risen much above the horizon.”18 The Kentucky gentleman, “slender, but very erect,” impressed Dorr as “unassuming and engaging … his eyes bright and sparkling, particularly in conversation.” Dorr appreciated the “amiable dispositions of the distinguished statesman toward a young stranger in the West.”19

Henry Clay, then a Jeffersonian Republican, had recently brokered a major legislative compromise that pacified, at least temporarily, political conflict between slave states and free states over slavery’s expansion into U.S. territories. As Speaker of the House of Representatives, Clay had proposed and steered passage of the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which split the Louisiana Purchase territory at the latitude of 36° 30’ and banned slavery north of that line, excepting Missouri, which would be admitted into the Union as a slave state, while Maine, split off from Massachusetts, would be admitted as a free state to maintain a numerical equilibrium in Congress between free and slave states. Clay entertained Dorr at his almost 600-acre Ashland estate, which Dorr described as “the most elegant place immediately in the vicinity of Lexington, though not equal to Chaumiere, the [nearby] residence of Col. [David] Meade.” Dorr said nothing in his diary of the fifty sl...