![]()

CHAPTER ONE

FIRST ENCOUNTERS

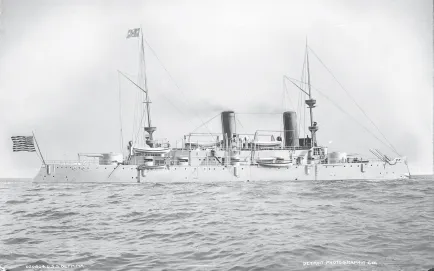

At a little after five o’clock in the morning, May 1, 1898, the Battle of Manila Bay commenced. It was quickly over. The American squadron, led by Commodore George Dewey in his flagship Olympia, completely destroyed the antiquated Spanish fleet at Cavite. Dewey’s force received little damage and suffered but a handful of wounded. The importance of the battle, however, was not in tonnage sunk or men killed.

Dewey’s decimation of the Spanish fleet set into motion a series of events that propelled the United States into the pantheon of world powers. During the next few months, the United States would roll over the Spanish garrisons in Cuba and Puerto Rico. But Dewey’s victory was also the fountainhead of the Philippine-American War. Within days after the battle, plans were being devised in Washington to send a five-thousand-man expeditionary force to occupy the Philippines, or at least parts of the Philippines. The reasons for this force and its objective have been debated for over a century. Some argue the military acquisition of the archipelago was the natural result of America’s imperialist urge. Others contend it was to improve overseas markets. Still others would say it was essentially an accident: that given the presence of Japanese and European powers in the area, America had no choice but to send troops to the islands. Whatever the reason, the United States began to marshal its forces.1

Congruent to this mobilization were the endeavors of the Philippine independence movement, the Katipunan, which had earlier shown nascent fighting abilities but was hampered by internal squabbles and was unable to dislodge the Spanish from its colony. In December 1897, after a negotiated settlement with the Spanish, the movement’s leadership under Emilio Aguinaldo left in exile to Hong Kong. The following April, in Singapore, Aguinaldo had contacts with American officials who may or may not have promised Philippine independence once the Spanish were removed. He returned to the Philippines on May 19, 1898, aboard the U.S. revenue cutter McCulloch. On June 12, Aguinaldo, who had a few weeks earlier proclaimed himself dictator and assumed command of all insurgent forces, declared Philippine independence from Spain. As Dewey’s squadron sat idle in Manila Bay, the Filipinos launched an offensive that neutralized the Spanish military presence throughout the archipelago, save for the garrison in Manila. The Filipinos had little in the way of artillery and no navy, and thus they could not realistically hope to take possession of the city. Aguinaldo needed the United States to capture Manila.

What evolved was a peculiar geometry. At first, the United States appreciated the work of the Filipino forces and offered them various types of support. The landscape soon changed. The first American infantry expedition landed at Cavite on June 30, the second on July 25. Meanwhile, Spanish and American officials negotiated the future of the islands. It has long been assumed that the Spanish desperately wanted to leave but would not be disgraced by surrendering to the Filipinos and, consequently, went through an arranged or “sham” battle with the Americans. This first battle of Manila occurred on August 13. It began with the navy shelling Spanish positions, followed by the infantry, made up of largely State Volunteer units, landing and capturing the city with few losses to either side. The centuries-old Spanish era was over.

With the Spanish out of the picture, the United States found itself face to face with Aguinaldo’s Army of Liberation. Under Maj. Gen. Wesley Merritt, the United States occupied Manila, prohibiting Aguinaldo’s army from entering the city. On December 10, the Treaty of Paris was signed, with Spain ceding to the United States the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico for $20 million. This, coupled with not being permitted to enter the city, enraged Filipino forces. A long, tense standoff ensued, with the Filipino troops surrounding the city and the United States controlling the bay and port. The apprehension was lifted on February 4, 1899, at San Juan, a suburb of Manila, where shots rang out between American and Filipino sentries. The Philippine war had begun.2

Throughout February intense fighting took place on the outskirts of Manila. The battle of February 5 was the largest of the war, fought over a sixteen-mile front. The State Volunteer units performed well, and with the aid of navy gunboats pushed the Army of Liberation farther and farther north of the city. By mid-February U.S. forces, now under the command of Maj. Gen. Elwell S. Otis, were near Caloocan, five miles north of Manila, and over the next few months the Americans drove northward into Bulacan and Pampanga provinces. Due to administrative bungling and an insufficient number of troops, the American offensive stalled during the summer. Although Aguinaldo’s army was badly mauled, it was not defeated, and it withdrew north temporarily out of reach of Otis and his men.

The time frame of May 1898 through the summer and early fall of 1899 saw two distinct military stages. The first was the defeat of the Spanish and the second was the initial fighting with Philippine forces around Manila and in central Luzon. Largely the navy undertook the first stage; largely the army undertook the second stage. Importantly, the two branches of service saw the Philippines at different points in time and within different political assumptions and circumstances. In terms of American-Philippine relations, for the navy, the battle of Manila Bay was an act of liberation; for the army, the battle for Luzon was an act of conquest. This distinction is apparent in the stories of the period.

Before the stories are discussed, it would be helpful to consider the American sailor and soldier and their world. Despite decades of post–Civil War neglect, both branches of the service made major improvements in the 1890s. The navy had modernized its fleet, inspired by the popularity of Alfred Thayer Mahan’s The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660–1783. The army in 1898 was less advanced, initially reliant on State Volunteers, who were followed in 1899 by the United States Volunteers. But the war also saw the development of the Regular army forces. In fact, as Brian McAllister Linn points out, the Philippine endeavor saw the transition from the “Old Army” to the new, with the latter being characterized as young, “self-sufficient, innovative, and intelligent as well.”3

The forces were adequately commanded. Naval officers at the time were graduates of Annapolis. The officers in the Regular army were from West Point or at least had specialized training in an army school. Many of the Regular officers did have combat experience, either in the recent war with Spain or on the American Plains. The higher-ranking officers certainly had combat experience, with some—such as the navy’s Dewey and the army’s Brig. Gen. Arthur MacArthur, Brig. Gen. Loyd Wheaton, and Brig. Gen. Joseph Wheeler—having served in the Civil War. The officers in the State Volunteer organizations were different. Save for the highest ranks, most were not career military men; rather, they were often professionals and college students who enlisted for a variety of purposes. Few of these officers had seen combat, save for those who had been in Cuba or Puerto Rico.

Multiformity marked the ranks of the army enlisted. For both Regular and Volunteer, the average soldier was young (late teens to midtwenties) and white, although there were six African American regiments that saw service. The soldiers received little training, usually just six weeks. All of the men were poorly paid. Many of the soldiers, especially in the State Volunteers, were from the West. Immigrants dotted the ranks. There were a relatively substantial number of the college educated, men inspired by the notions of the strenuous life, muscular Christianity, and manifest destiny that existed in the country at the time.4

One important common denominator for all was the character of their early education. Soldiers and sailors—from those who graduated from the academies to those with a few years in a rural schoolhouse—were imbued by a pedagogy that was ideologically simple. Although such innovative and complex ideas like Social Darwinism roiled within colleges and government, American schoolchildren received essentially a puritan education, one that tied morality to all elements of the universe and stressed a number of unquestionable mandates: to love country and family, to work hard in order to achieve prosperity, to suffer stoically, and to believe in the superiority and infallibility of the United States. Exemplifying these mandates was the settlement of the West, pioneers being the embodiment of the American ideal.5

This education was the fundament of the soldier’s belief system. The men were not conscripts. Their identity was fired with patriotism and devotion to service. Consequently, most veterans believed that the United States was morally right in its annexation of the Philippines. These sentiments were in keeping with the prevailing mood of the country: throughout the United States swept an intense burst of romantic nationalism that equated patriotism with progress and military might with virtue.

Such conservative sentiments were in no small way a reaction to a marked physical and psychological convulsion that enwrapped America at the time. A serious economic depression began in 1893 and was still in existence until the war with Spain. Industry barons, antitrust legislation, and fledgling unions created a confused economic landscape, and one replete with severe labor violence. African Americans, escaping lynching in the South, found themselves embroiled in race riots in the North. Eastern cities were teeming with immigrants, mostly European Catholics and Jews, who created urban ghettos as well as anxiousness within a predominantly Anglo culture. And as a psychological underpinning to this social uncertainty, the West had been conquered; the country was no longer an open plain of possibility, but one with a physical border that hemmed in the American pioneer identity. This loss of pioneer identity is crucial in understanding the perspectives of the writers about to be presented.

Clarence Lininger was surely a man affected by his times. His book, The Best War at the Time, published in 1964 when the author was eighty-four, reveals his decision to fight in the Philippines:

The ethics of war did not concern me…. The wave of imperialism sweeping the country seemed to me wholly right, the logical outgrowth of the great movement that had carried the pioneers from the Atlantic to the Pacific. We had conquered the Alleghanies [sic], pushed through the forests of Ohio and Indiana, crossed the boundless plains and surmounted the towering Rockies. The jump across the Pacific was just another leap in the westward course of empire and could be accomplished as effortlessly as the others. Injustices must be wiped out. The blessings of liberty must be brought to a backward people. I must, I felt I must, join this great modern crusade!6

This evangelical need was not the major reason why men joined the service—boredom at home, the lure of adventure, an immigrant’s escape into the status quo were dominant factors for enlistment. But Lininger’s proselytizing did exist in many veterans. It certainly existed in the ideology promoted by certain political leaders in the United States, President William McKinley not the least among them, as well as religious figures, who saw the involvement in the Philippines as a great moral campaign to uplift the heathen (Catholic) Filipinos. Such uplifting, however, could only be done by force. Linking the myth of the Frontier, national expansion, and his own ideas on the strenuous life, Theodore Roosevelt championed the “savage war”—a war against an inferior race—as being a righteous war, a war that would eventually raise the barbarian people through tutelage and progress.

Such was the world of the men who went to the Philippines in 1898 and 1899. The writers who remembered these early days of American involvement stress two major ideas. One is the natural environment. It would be difficult to imagine the astonishing change in land and culture the men underwent. At the time, virtually nothing was known about the islands, and the men were truly strangers in a strange land. The writers include descriptions of the physical landscape and the people who live within it, at times because of its beauty or foreignness and often to illustrate the writer’s sense of alienation or the absurdity and horror of the combat moment. Another prevalent theme is the celebration of the collective. The stories reveal life within a group of men: sometimes small, daily events and sometimes dramatic battlefield accounts, sometimes feelings of emasculation and helplessness, and sometimes the joy of comradeship. These stories tell what it was like to first encounter the Philippines and, for many, to first encounter combat.

The Battle of Manila Bay

Commodore Dewey encountered the war first. After the explosion on board the battleship Maine and the subsequent declaration of war against Spain, Dewey, the commander of the U.S. Asiatic fleet, began preparations to confront the Spanish in the Philippines. On April 27, 1898, in his flagship Olympia, he set sail from Mirs Bay, Hong Kong. Dewey’s was a risky plan: the fleet was underequipped and the supply line stretched back to California. Intelligence coming from Americans in Manila was sketchy. Observers overrated the Spanish ships and personnel; few people understood that the American ships were far better designed and the Spanish far worse. Indeed, British members of the Hong Kong Club told Dewey that it was not possible to get a bet on the success of U.S. ships because the odds were so much against them. The British noted that the Americans were fine fellows but were convinced that “we shall never see” Dewey’s sailors again.7

At the time of the war’s outbreak, Dewey was sixty years old. Although he fought with Farragut during the Civil War, his subsequent military career was relatively undistinguished, and it was only through political pull that he was able to acquire the command of the Asiatic fleet. As he sailed toward the Philippines, Dewey must have realized that the upcoming battle could well be the highlight of his military career. If he did have this thought, he certainly would have been correct.

Dewey recalls the battle of Manila Bay in his 1913 autobiography, supposedly ghostwritten by noted war correspondent Frederick Palmer and based largely on the reports of the commodore’s aide, Nathan Sargent. Dewey was nearly seventy-six when it appeared. He had received a hero’s welcome on his return to the United States in 1899, and based on this national acclaim entered the presidential race in 1900, withdrawing after a series of public relations mistakes. For the decade after the battle, he led a life of style and comfort. The book, then, is clearly an exercise in retrospection, written by man late in life.

Fig. 1. USS Olympia (Library of Congress)

The New York Times noted that his book paid “an attention to accuracy [making it] valuable to historians and with a fluency and skill that make it as lively as fiction.”8 This seems fair. A case in point: the squadron entering Manila Bay in the hours before the battle. Here Dewey compares his present situation to that of his Civil War experiences, including the time when his ship, the paddle-wheeled Mississippi, ran aground at Port Hudson in 1863. In making this comparison, he i...