![]()

PART I

There are no choices here,

this is devotion, this work

has nothing to do with wages,

this work is a universe, yours

with dimensions drawn to fit

only you.

LUCIA CORDELL GETSI, “NURSING”

I have never been so afraid.

Welcome to our neighborhood. See the clothes we’re taking off the lines? Nursing students, the world over must leave their old lives behind and put on the uniform of servitude. People are fearful, of course, in any new area of study, but nursing students know their actions or missteps may forever alter the course of a person’s life. When we are students, first learning the art of nursing, fear of failure and exhaustion sew themselves inside our lab coat pockets. They weigh us down. Hours devoted to studies and clinical labs are grueling, but through the fog of fatigue we rise, for we have been called. Upon graduation, our uniforms will change, but emotional labor and rough shifts do not lose their intensity.

![]()

LINDA MAURER TUTHILL

A School for Hands

After the ward rounds, basin baths,

the rigors of making

occupied beds, bottom sheets

stretched drum-tight,

we student nurses sigh into afternoon.

The nourishment cart rattles

in the corridor, dispensing juice

and Lorna Doones or graham squares.

Aides refill metal water pitchers

beaded with sweat, ice already failing.

Expected to offer P.M. back rubs,

we pull flimsy curtains for a hint of privacy.

Fancy French massage terms:

effleurage, petrissage, friction, learned

in class, ping pong in our heads.

Our bodies rock, a rhythmic blur of blue,

as supple hands knead and stroke

from tail of spine to shoulders.

At this school for hands, we speak

with the warm vowels and consonants of touch.

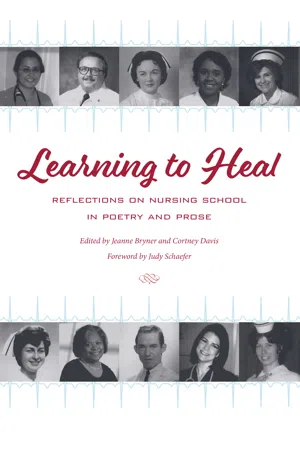

Linda Maurer Tuthill, Johns Hopkins Hospital School of Nursing, 1963. Courtesy Linda Maurer Tuthill.

![]()

SAUNDRA SARSANY

For Now

Everything here is quiet

and I’m thinking

of the day I left home

for nursing school in 1957.

I had to say goodbye

to my family. When we

arrived, we were sent home.

Our school was new and not

ready. So back home

for two more weeks, then

start over again. Two weeks

into classes, I had my appendix

out. Finally, back

and in Nursing Arts lab, you

Miss Beamer, said my petticoat

(a can-can slip) made too much noise.

You sent me out to the restroom

where I took it off. My slip

was new and not ready to be mute.

You were very strict, very critical.

Saundra Sarsany, Trumbull Memorial Hospital graduate, 1960. Courtesy Saundra Sarsany.

We were so scared, called you

the witch. Maybe we can start

over again, Miss Beamer. Tea?

A ham sandwich between

dusting stars? A happy meal?

Saundra Sarsany, flight nurse, 1986. Courtesy Saundra Sarsany.

I Became a Nurse

Because my Aunt Peg

was an Army Nurse in WWII,

because she let me play

with her nurse’s caps,

lieutenant bars and med ampules.

Because I worshipped her,

because she gave me a picture

of the Nightingale Pledge for my room.

I knew then I would also be a nurse.

Because of Aunt Peg, I went to the library,

read every volume of Sue Barton,

Registered Nurse, over and over.

Because there were so many fields

of nursing. Because of her, I went

into nursing school at her alma mater,

found out how I loved caring for patients.

Because of Aunt Peg, I found my life

calling, calling, calling.

Saundra Sarsany’s Aunt Peg Noderer, First Lt. Army Nurse Corps, WWII, 1942–1944, field hospital in England. Courtesy Saundra Sarsany.

![]()

BARBARA BROOME

I Am Not Superwoman

I can name a room full of people who say they always wanted to be a nurse. But, I’m not one of them. I grew up in rural Ohio, where my parents worked hard to make ends meet. Often we were without heat in the winter because we couldn’t afford both heat and food, and food was more important. Those cold evenings, I was happy to huddle under extra blankets and watch TV.

In my eyes, my dad was the biggest man in the world. He worked full time at a bumper plant and part time as our township constable. My mother cleaned houses for teachers, a dentist, and lawyers, professionals who lived in what we used to call “town.” In reality, it was only a village, but it seemed like a big town to a kid who never saw traffic lights. In those days, black families, intentionally segregated, lived grouped in one area and white families lived in the “richer” areas with conveniences such as running water and sewage. My family had pumps in the yard and outside toilets. To this day, I believe my early environment, so divided between poor and “wealthy,” made me want to be “like them.” Not really sure what like them meant, but I wanted to be able to take a bath in a nice tub with bubbles and hot water out of the tap, water that didn’t have to be heated on the stove.

Because my mother needed help cleaning houses, I missed a lot of school. We were paid a whopping seven dollars per house. If I went with mom, we could clean two homes a day. Although we never made a lot of money, the families often gave us clothes and shoes, things I didn’t have in my closet. These hand-me-downs were the only store-bought clothes I owned; the others were homemade, using patterns from McCall’s, Butterick, and Simplicity. Mom taught me to sew when I was nine. Those corduroy jumpers and gingham skirts were made with patience and attention. One of my favorites was a gray jumper with pockets. I wore that jumper until I couldn’t hold my breath enough to fit inside it. The kids who made fun of me didn’t know how long it takes to press a pattern and line up a zipper—we may have been poor, but I remember all the ways in which I was loved.

Barbara Broome, Dean, Kent State University College of Nursing, 2014. Courtesy of Barbara Broome. Photo by Bob Christi.

Maybe because I missed a lot of school, I had a love-hate relationship with it. I enjoyed school when I was able to attend because it was fun to learn, but I also hated it because I was the outsider and had few friends. In May 1966, I graduated from high school, and my only aspiration was to get a job. I found work in a collection agency—ironically one that had my parents in collection—but it was a job, and even earning less than $1.50 an hour, I was proud. In August, I was married and continued to work. Soon, an opportunity to work at a local hospital’s business office presented itself for $3.05 an hour. I worked there until, two years later, my husband and I had our daughter, a bundle of joy. When I returned to the hospital, I landed in the admissions office until, three years later, we welcomed our son. With a new baby and a toddler, back to the hospital I went, but this time as the admissions supervisor, with responsibility for inpatient, outpatient, and all cost containment programs. Still, nursing was the furthest thing from my mind.

After seven years at the hospital, I left to become the office manager for a local health-care specialist. A year later, I was unemployed. Like so many, I never saw it coming. My self-esteem was shattered, and I was angry. For the first time in my life, I applied for and received unemployment compensation. But I wanted to work—and I realized the need for further education.

I decided that only I could control my destiny and not give others the ability to destroy me. Then, within six months of losing my job, my father died of cardiac arrest. I had a solid background in the business workings of health care, and now I was introduced to the challenges of caregiving in a dramatic way. I began to consider that nursing might be a path for me, but I was unsure. Wanting to be sure nursing was a calling and not simply an impulse based on my long-term association with hospitals, I stepped back from health care completely and took a job as a manager and buyer for an office supply company. In less than six months, I knew this career was not for me—nursing was. I applied to a licensed practical nursing program, Hannah Mullins in Salem, Ohio, and I was accepted.

Barbara Broome (lower left, first seated student in row one) with her fellow nursing school graduates, Hannah E. Mullins School of Practical Nursing, 1994. Courtesy Hannah E. Mullins Archives.

I drove more than fifty miles a day to class after getting up, dressing my children, taking them to the sitter, and leaving at five in the morning to arrive in class by seven. My husband was working full time, and we both left the house by 5:00 A.M. It was a grueling schedule, but I was determined. My patients, especially my minority patients, often offered inspiration and encouragement, perhaps sensing that, like them, I had to work hard for my education and my future. My dedication paid off, and I was voted class president. At my graduation in 1985, it was me, a girl who used to scrub floors with her mom, the girl who wore handmade gingham blouses, giving the final class address. What an honor! After passing my licensure examinations, I worked at a local nursing home and in a year applied at the hospital where I’d previously worked; I was hired for the Intensive and Cardiac Care Step-Down Units.

My mother was so proud of me. She would tell others my daughter saves lives. “I am so proud of her; we scrubbed floors together, and look at her now.” My husband and children had also been my constant cheerleaders, putting my semester transcript on the refrigerator, just as I did with their report cards. When I had good grades, my husband would take me and our kids to Dairy Queen. Those hot fudge sundaes were so good.

Unfortunately, my mom’s health began to fail. She’d been diagnosed with cervical cancer and had received radiation. I emptied every drawer of my nursing skills to help my mother, but her cancer spread and she developed lung cancer. Love was not enough; she died Thanksgiving Day 1986, after being in the intensive care unit on a ventilator for over a month. In memory of my parents, I understood the value of advanced education; health care was changing, and I wanted to be ready to be a part of its evolution. As a nurse leader, I’d be able to implement cutting-edge research and guide students to become creative and critical thinkers. My dream was to assist my community, my students, and my patients to function at their highest level—to live, not just exist. I wanted to help others experience minimal suffering at their journey’s end.

I called a family meeting. After intense conversations with my husband and children, we decided it was time for me to take the next step and become a registered nurse. I applied and was accepted to Kent State University and, while elated, I realized I had lots of hurdles ahead of me. Indeed, I was fortunate to have a husband and children who supported me. I continued to work full time as an LPN, go to classes, and be a student worker in Kent’s Anatomy Lab and the Tutoring Center whi...