![]()

PART I

Memories

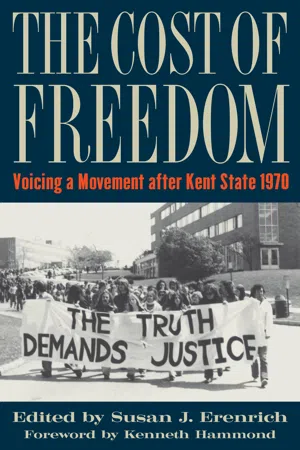

Left to right: John Adams, Joan Baez, Sarah Scheuer, and Martin Scheuer (Source: John Rowe)

John Rowe attended Kent State University as an undergraduate and graduate student from 1970 to 1980. He was a founding member of the May 4 Task Force, and an active member of the May 4 Steering Committee and the Kent State May 4 Center. His pictures captured all the major May 4 events for decades. John died in 2018 at the age of sixty-eight.

![]()

Anniversary, May 4, 1988

ELAINE HOLSTEIN

Elaine Holstein’s son, Jeffrey Miller, was one of the students killed on May 4, 1970, on the Kent State University campus. She worked to preserve his memory and to memorialize his death until her passing on May 26, 2018. This piece was written in 1988.

At a few minutes past noon on May 4, I will once again observe an anniversary—an anniversary that marks not only the most tragic event of my life but also one of the most disgraceful episodes in American history. This May 4 will be the eighteenth anniversary of the shootings on the campus of Kent State University and the death of my son, Jeff Miller, by Ohio National Guard rifle fire.

Eighteen years! That’s almost as long a time as Jeff’s entire life. He had turned twenty just a month before he decided to attend the protest rally that ended in his death and the deaths of Allison Krause, Sandy Scheuer, and Bill Schroeder, and the wounding of nine of their fellow students. One of them, Dean Kahler, will spend the rest of his life in a wheelchair, paralyzed from the waist down.

That Jeff chose to attend that demonstration came as no surprise to me. Anyone who knew him in those days would have been shocked if he had decided to sit that one out. There were markers along the way that led him inexorably to that campus protest.

At the age of eight, Jeff wrote an article expressing his concern for the plight of black Americans. I learned of this only when I received a call from Ebony magazine, which assumed he was black and assured me he was bound to be “a future leader of the black community.”

Shortly before his sixteenth birthday, Jeff composed a poem he called “Where Does It End?” in which he expressed the horror he felt about “the War Without a Purpose.”

Was Jeff a radical? He told me, grinning, that though he might be taken for a “hippie radical” in the Middle West, back home on Long Island he’d probably be seen as a reactionary.

So when Jeff called me that morning and told me he planned to attend a rally to protest the “incursion” of U.S. military forces into Cambodia, I merely expressed my doubts as to the effectiveness of still another demonstration.

“Don’t worry, Mom,” he said. “I may get arrested, but I won’t get my head busted.” I laughed and assured him I wasn’t worried.

The bullet that ended Jeff’s life also destroyed the person I had been—a naïve, politically unaware woman. Until that spring of 1970, I would have stated with absolute assurance that Americans have the right to dissent, publicly, from the policies pursued by their Government. The Constitution says so. Isn’t that what makes this country—this democracy—different from those totalitarian states whose methods we deplore?

And even if the dissent got noisy and disruptive, was it conceivable that an arm of the Government would shoot at random into a crowd of unarmed students? With live ammunition? No way! Arrests? Perhaps. Tear gas? Probably. Antiwar protests had become a way of life, and on my television set I had seen them dealt with routinely in various nonlethal ways.

The myth of a benign America where dissent was broadly tolerated was one casualty of the shootings at Kent State. Another was my assumption that everyone shared my belief that we were engaged in a no-win situation in Vietnam and had to get out. As the body counts mounted and the footage of napalmed babies became a nightly television staple, I was certain that no one could want the war to go on. The hate mail that began arriving at my home after Jeff died showed me how wrong I was.

We were enmeshed in legal battles for nine years. The families of the slain students, along with the wounded boys and their parents, believed that once the facts were heard in a court of law, it would become clear that the governor of Ohio and the troops he called in had used inappropriate and excessive force to quell what had begun as a peaceful protest. We couldn’t undo what had been done, but we wanted to make sure it would never be done again.

Our 1975 trial ended in defeat after fifteen weeks in Federal Court. We won a retrial on appeal, and returned to Cleveland with high hopes of prevailing, but before the trial got under way we were urged by both the judge and our lawyers to accept an out-of-court settlement. The proposal angered us; the case wasn’t about money. We wanted to clear our children’s names and to win a judicial ruling that the governor and the National Guard were responsible for the deaths and injuries. The defendants offered to issue an apology. The wording was debated for days, and the final result was an innocuous document, stating that, “in retrospect, the tragedy … should not have occurred” and that “better ways must be found to deal with such confrontations.”

Reluctantly, we accepted the settlement when we were told this might be the only way that Dean would get at least some of the funds to meet his lifelong medical expenses. He was awarded $350,000, the parents of each of the dead students received $15,000, and the remainder, in varying amounts, was divided among the wounded. Lawyers’ fees amounted to $50,000, and $25,000 was allotted to expenses, for a total of $675,000.

Since then we have lived through Watergate and Richard Nixon’s resignation, crises in the Middle East and in Central America, and the Iran-contra affair. To most people, Kent State is just one of those traumatic events that occurred during a tumultuous time.

To me, it’s the one experience I will never recover from. It’s also the one gap in my communication with my older son, Russ: Neither of us dares to talk about what happened at Kent State for fear that we’ll open floodgates of emotion that we can’t deal with.

Whenever there is another death in the family, we mourn not only the elderly parent or grandparent or aunt who has passed away; we also experience again the loss of Jeff.

This piece appeared in Kent & Jackson State 1970–1990, edited by Susie Erenrich. It was reprinted by permission of The Progressive Inc. © 1988.

![]()

A Tribute to Arthur Krause

Delivered at Kent State University, May 4, 1989

KENDRA LEE HICKS PACIFICO

Kendra Lee Hicks Pacifico has been part of the extended May 4 Family since 1982. At that time, she played the role of Allison Krause in a production of Kent State: A Requiem at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and at the 30th annual May 4 Commemoration at Kent State. She moved to Kent in 1988 and has become instrumental in organizing the annual May 3 candlelight vigils. This piece was written in 1990.

I am here before you to pay tribute to a man—Arthur Krause, the father of Allison Beth Krause, a student slain in a parking lot on the Kent State University Campus on May 4, 1970.

Most of us here know him as the most prominent leader in the quest for justice for the murders that took place here in 1970, a man whose efforts enable us to gather here today.

When I questioned those who knew him well, I heard these descriptive words mentioned: “strong,” “stubborn,” “vital,” “larger than life,” “warm and generous,” “fierce.” I heard phrases like “the iron man of the Kent State family,” “he was relentless in his quest for justice,” “I felt lucky that I had the benefit of his friendship,” “we are richer for having known him.” I feel fortunate to have met him.

America first heard from Arthur the day after the shootings. When speaking with television newsmen, he expressed the sentiments of the horribly shocked citizens of this country: “Have we come to such a state in this country that a young girl has to be shot because she disagrees with the action of her government?”

We stopped and listened to him. And we heard from him again. For the next four years, Arthur continually asked for justice. He wanted someone held accountable for the death of his daughter. He called for congressional hearings and federal investigations into the shootings. He appealed for the right to a day in court. He pushed through the Ohio District Court, the US District Court, the US Court of Appeals, and finally to the US Supreme Court, all the while trying to break down the wall of Ohio’s sovereign immunity law—the law that said defendants could not be sued without first giving their consent to such an action. But he would never back down. As Martin Scheuer, the father of Sandy Scheuer, once told me, “Arthur was a man of principle.”

In the first year of the struggle, Arthur was joined by Peter Davies, an ordinary citizen from Staten Island, New York, who had been appalled at the shootings and he himself had spent months researching the shootings, looking for clues to explain why the National Guard had fired:

For almost a year … we tilted at windmills alone, but without his dynamic strength I could not have stayed the course. Arthur’s quest was never idealistic. He was always a realist in dealing with the Nixon administration, and despite his grief and anger, whenever we accomplished something that seemed to me a big step forward, he would laugh and say, “that and ten cents’ll get us a cup of coffee.” We had more cups of coffee than I care to remember.

Elaine Holstein, the mother of slain Jeff Miller, described Arthur as “totally indispensable.” She writes, “Indispensable—because my life in those years after our children were killed and we struggled to find some semblance of justice—would have been far more hellish without the Rock of Gibraltar that was Art Krause.”

In 1971, Arthur and Peter were joined by Rev. John Adams of the United Methodist Church. This addition to the team had a very positive effect. As Sanford Jay Rosen, attorney for the families in the final settlement, observes: “Two people, Arthur Krause and John Adams, are most responsible for the measure of justice the Kent State victims and their families have received. Arthur brought anger and passion to the cause. John brought hope and compassion. Without these two, all would have been for naught.”

Arthur’s passion was so deep due to the fact that he knew what lay at the root of the problem. As he recalled his life, he said, “I was like everyone else, and then this happened to us.” In recalling other episodes of extreme violence in our country before May of 1970, he said:

I feel a great sense of guilt because I realized what was going on but didn’t do a damn thing about it. Like most Americans these days, we sit on the fence and depend on the lawyer, the church, and the government to do whatever should be done, but if the government doesn’t have the right people on the job, nothing will be done … and we, the people, have to make the government good. Apathy will not be part of my make-up anymore. Apathy is what caused Kent State.

In 1975, Arthur’s four years of persistence paid off. The vic...