![]()

© 2010 Diane Moczar

All rights reserved. With the exception of short excerpts used in articles and critical reviews, no part of this work may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in any form whatsoever, printed or electronic, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-0-89555-906-7

ISBN: 978-0-89555-918-0

ISBN: 089-555-918-8

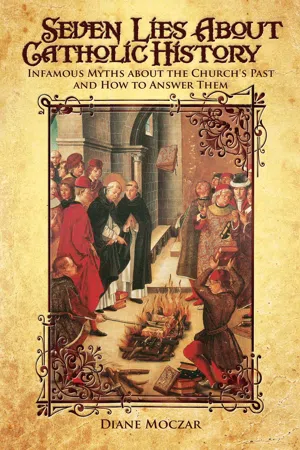

Cover design by Tony Pro.

Cover image: Spanish painting from the 1400s by Pedro Berruguete showing the miracle of Fanjeaux. According to the Libellus of Jordan of Saxony, the books of the Cathars and those of the Catholics were subjected to trial by fire before Saint Dominic. The Catholic books were rejected three times by the flames. Scanned from a history book. Wikimedia Commons.

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

TAN Books

Charlotte, North Carolina

2010

![]()

CONTENTS

Preface: Why Tell Historical Lies?

Introduction

1. The Dark, Dark Ages

2. The Catholic Church, Enemy of Progress

3. A Crusade against the Truth

4. The Sinister Inquisition

5. Science on Trial: the Catholic Church v. Galileo

6. A Church Corrupted to the Core

7. A Black and Expedient Legend

8. And There Are More …

Appendix 1: How to Answer a Lie

Appendix 2: Sources Used and Recommended

About the Author

![]()

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I wish to express my grateful thanks to Todd Aglialoro, my editor, for his professional guidance; I could not have completed this book without it. All those little conflicts over content, fights about footnotes, and tiffs about titles are now completely forgotten. Or almost.

![]()

PREFACE

WHY TELL HISTORICAL LIES?

Lies about history are told, written, and passed down through generations for a variety of reasons. States create lies about rival states; an example of this is the Black Legend, invented mainly by England in the early modern period to blacken the reputation of its great rival, Spain. England’s motives were political, economic (Spain had struck it rich in the New World while England had not), and religious (the Spanish king was the Catholic champion of Europe, whereas English monarchs were supporting the Protestant cause). More recently, anti-Catholic and antilegitimist authors have told lies about the wartime regimes of Marshal Pétain in France and Franco in Spain. Communist writers lie about capitalism, capitalists about workers, and Renaissance historians about the Middle Ages. There can also be a real temptation to distort history for reasons of patriotism, or to cover up the failings of one’s own party or religious leaders. (Catholics are not immune to this temptation.)

Historical lies, in short, are not necessarily told from religious motives, although religion is often one reason— sometimes the most important one—for their creation. In this book we will examine seven lies that do originate from religious motives and which have the Catholic Church as their target: either directly—as with the Inquisition, the Galileo case, the Church’s alleged opposition to progress, the putative corruption of the Church before the Reformation, and the postwar attacks on Pope Pius XII—or indirectly, as with the Black Legend, the Crusades, and the Middle Ages.

In cases in which historical lies target the Church directly or exclusively, there are, again, a variety of specific motives for the attacks. Atheists are always happy to find some issue with which to discredit the Church, and ex-Catholics bearing a grudge against their former spiritual mother are often both rabid liars and prolific writers.

The most thoroughgoing and persistent religious historical lie seems to be the oddly unhistorical view that most Protestants take of pre-Reformation history. They posit an early Christian community of believers with a very loose ecclesiastical organization and no fixed hierarchical structure, only a couple of sacraments, and a few doctrines that fit whichever sect they belong to. This happy situation lasted, in their minds, until the Emperor Constantine stopped the persecutions and legitimized Christianity. Constantine supposedly reshaped the structure and doctrines of the Church by meddling in ecclesiastical affairs, and this Church-State

coziness changed Roman Christianity into what became the bad Catholic Church we have today—while the true believers went underground in order to practice their pure and simple faith, only emerging into daylight with the dawn of the Reformation.

This scenario is incredible (in the literal sense) to anyone familiar with the mass of available early Christian documents and the history of the first three centuries. The myth survives mainly due to historical ignorance, as well as ideology, and the reason I do not deal with it directly in this book is that the cure for it is an entire course on early Western Civilization. Portions of this mythical history, however, will turn up in several of the following chapters.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

You have undoubtedly come across some of the seven scenarios discussed in this book (and probably many more), all of which present Catholic history in an unfavorable light. Confronted with these assaults on the Catholic past, you may have recalled the spate of public apologies issued by some of the recent popes and decided that we Catholics have much to be ashamed of in the behavior of our ancestors. It might be better, perhaps you found yourself thinking, if we let all those dark centuries bury themselves and focused instead on an upbeat and non-confrontational future.

Importance of Understanding the Lies

The trouble with this attitude, other than the fact that it invokes yet another historical lie, is that the controversies do not go away. The rest of the world—history professors, textbook writers, filmmakers, media figures, Protestant apologists, anyone with an axe to grind against the Catholic Church—will not let us simply erase our past and go on. They continue to rake up their version of Catholic history, ad infinitum, and wield it with the intent of harming the Church. If we refuse to learn the reality of our history, we are reduced to twiddling our thumbs and looking sheepish when someone brings up the Inquisition, for example. When we do not know enough to refute the lies, we reinforce them by default—or we secretly buy into them ourselves.

We would do much better to confront the past of our Mother the Church objectively. History is God’s acting in the world, most immediately through His own Church. Insofar as His fallible instruments are men, they can act ineffectively, stupidly, or maliciously, and thus affect history negatively. It very rarely happens, however, that the drama of Catholic history is performed exclusively by dumb, inept, or malicious Catholics. At critical moments, in fact, the actors are often saints—as we shall find in all seven historical periods that we shall examine.

We must keep in mind that although the Father of Lies is behind all lies, either directly or indirectly, any given purveyor of a lie may be completely unconscious that he is falsifying the historical record. There have certainly been rabidly anti-Catholic writers who deliberately distorted history to put Catholics and their Church in a bad light, but not all historical distortion is deliberate. For example, a historian may have a deep antipathy for monarchy—considered the most perfect and natural form of government during the Christian centuries—and therefore find it difficult to deal objectively with the historical manifestations of monarchy. The same goes for more recent authoritarian Catholic governments, such as that of Salazar in Portugal. An economic historian sold on capitalism might find more to criticize in the guild system than would a less-biased researcher. And what feminists find to criticize in the Catholic centuries would take far too much space to go into here.

On the other hand, some historians distort history in the other direction, seeking to portray it as they would like it to be. Some romanticize the Catholic past to the point of ignoring real problems in the Church and the flaws of many Catholic historical figures. Then there is the bizarre case of John Boswell, a Catholic historian who died of AIDS in 1994. In works such as the book Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality, he argued that the Church had formerly tolerated and even approved of perverse unions and had only changed its position in recent times. Boswell supported his thesis with a staggering collection of erudite footnotes to texts in several languages; only after his death did it come out that much of the book was based on the flawed work of his graduate student assistants.

The challenge for the Catholic historian, therefore, is to maintain an attitude of both objectivity and sympathy in dealing with the Catholic past as it truly was, based on competent and comprehensive research. More will be said about this difficult task in Appendix 1, but the first step is obviously to decide on a topic for study, assemble reliable sources on the topic or period chosen, and then devote the necessary time to studying them. Appendix 2 provides some reading suggestions, but there are many more good sources available, quite a few of them online. Even Wikipedia has some excellent introductory articles, with sources cited, including one on the new revisionism about the Spanish Inquisition. Quite a few out-of-print but worthwhile volumes can also be found and read on the Internet.

Who Needs This Book?

Catholic apologists need it. They are usually not trained in history, and yet they find that Protestants of all stripes have an ingrained, distorted view of history that interferes with dialogue on doctrine. History is, in fact, vital to Catholic apologetics: “To be deep in history,” wrote Newman famously, “is to cease to be Protestant.”

Students need it just as much. After writing dozens of instructors’ manuals, student guides, and test banks for numerous mainstream college history textbooks, my hair has ceased to stand on end at the lies embedded in these works. In only one or two instances have I been able to get an egregious error removed from a textbook, and even then the subtle bias of the work remained. I pity the many thousands of instructors and students who use these secular humanist and subtly anti-Catholic books without an antidote to the poison at hand. I hope this book may be an antidote.

Homeschoolers need it. Even if they have orthodox books to work with, some of these lies are not specifically addressed in them for want of space. And the additional resources this book provides will help develop the research skills of older students.

Ordinary Catholics need it, if they have ever come up against a negative argument about Catholic history that they could not answer. This book does not by any means answer all historical arguments, but it takes up those that are most prevalent and most insidious. When a non-Catholic friend spits out the word “Inquisition” and shudders expressively, one need no longer shudder with him. The reader of this book can say, “Oh yes, I was just reading about that. Let’s talk about it.” This does good to souls, as well as helping to strengthen our own appreciation for Holy Mother Church.

Why Call Them “Lies”?

I try to present each of these historical lies in its strongest formulation. In order to understand any controversy, we must try to get inside the opposing mentality and see the situation from that perspective. Only after we have understood the terms of the argument in their best and most persuasive forms can we evaluate it and determine whether it is true or false. So far, this sounds like the way anyone ought to deal with any historical question—for example, whether the Persian Wars would have been over sooner had the Greeks been more united. No one uses the word “lie” in describing differences of opinion on an ancient Greek topic, so why am I using it in the title of this book?

My reason for the negative characterization is that each of the positions we will examine has a dimension beyond the historical. Facts are neutral, but willful distortions of the facts are lies; and once the lies are articulated, they do not cease to be lies even when they are innocently repeated by those who are unaware of their mendacity. Thus we will have to disentangle, for each of our seven topics, the actual historical situation from the spin put upon it by those who have used it as a weapon against the Church, from its first appearance right down to the most recent college textbook author and movie maker.

My discussion of each lie is necessarily brief; full treatment of each one would require one or more individual volumes for each topic. Fortunately, such work has been done or is in the process of being done on several of the lies, and I have included print and online resources for the reader to consult. If I succeed in enabling readers to spot these lies when they hear them, understand the truth behind the lies, and be armed with trustworthy sources for further information, my goal for this little book will have been achieved.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE DARK, DARK AGES

The Lie: The Middle Ages were one long Dark Age of ignorance and superstition, relieved only by the advent of the Renaissance.

The professor in the video is from a prestigious university in California. The video is one of a series of films made for distance learning in numerous colleges some years ago and also shown on television. The lectures are illustrated, and for the medieval segment most of the pictures are dark and grotesque to reinforce the idea that the Middle Ages were “dark.” The professor even observes that in the Middle Ages, when the sun went down, it got dark outside: picture of dark village on the screen. When he gets to medieval people, he refers repeatedly to the “awkwardness of their minds.” They were so awkward that they built buildings that fell down: painting of a building—actually dating from a later period—that has crumbled to the ground.

Just when the medievalist viewer, writhing in front of the screen, is muttering, “What about the cathedrals, you idiot!” and looking for a brick to heave through the TV, the professor admits that the period also produced cathedrals— and that their foundations went down the depth of a subway station and their spires soared hundreds of feet. Then he asks how, if their minds were so awkward, could medieval people have produced such beauty? Answer: to compensate for the awkwardness of their minds. We must also not forget that these awkward ignoramuses rarely even knew what time it was, since their sundials could not work in the dark. Apparently the professor had never heard of water clocks. (Needless to say, there is no mention of Thomas Aquinas, Roger Bacon, Bonaventure, Duns Scotus, or any other reasonably bright medieval thinker.)

Anti-medieval prejudice is built into our culture. A reporter covering a civil war in a primitive society will inform us that the participants exhibit “medieval barbarism.” Discussion of a bizarre cult will often include references to “medieval superstition.” Then there is “medieval torture,” used to describe really bad atrocities. Where did this view come from, and is it true? After all, if there is smoke, there must be fire somewhere, somehow, must there not?

Renaissance authors, Enlightenment philosophes, popular writers, and anyone who dislikes on principle any period strongly influenced by Christianity have all contributed to the “black legend” about the Middle Ages. In recent times, however, historians of the Renaissance have probably been the most persistent scholarly promoters of the lie. Enamored of their favorite historical period, they are fond of trying to show how wonderful it was by contrasting it with the bad old days that preceded it.

The First Lies about Medieval Times

This approach did not, of course, originate in the twentieth century but in the fourteenth, when the first Italian “humanists,” the original Renaissance men, began to idealize the classical culture of ancient Greece and Rome. In order to exalt that culture and to magnify the significance of their own literary work, they deprecated the culture of the more recent past as deplorably backward and insufficiently concerned with the real world. From there on the Middle Ages became, as we will see, a football for men of many persuasions to kick. Many writers since have disparaged the medieval period out of sheer ignorance or due to a naïve reliance on the opinions of the Renaissance writers. It should be noted here that most of those first humanists were Catholic, and that although some were critical of the Church and others were interested in introducing heterodox religious ideas, in most cases their disparagement of the Middle Ages did not spring from an animus towards Catholicism but from an exaltation of their own time, with its new artistic and literary styles and its optimistic view of man.

The fourteenth-century writer Giovanni Boccaccio thought that poetry had been dead until it was brought to life by Dante in the new age of “rebirth” that had just dawned. Dante was really, of course, a man of the Middle Ages in faith and mentality. He had even been born in the mid-thirteenth century, which was certainly one of the greatest medieval centuries. Nevertheless, Renaissance writers extolled both Dante and Giotto, Dante’s contemporary, as “modern,” while in the process—in numerous writings and with endless repetition—heaping scorn on all other medieval art, architecture, and thought. This attitude of men who were so convinced of the glory and superiority of their own historical period...