- 120 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

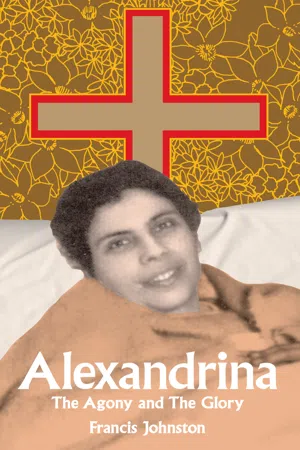

A Portuguese victim soul; crippled jumping from a window to escape a rapist; she suffered the Passion of Christ on Fridays; spoke with Our Lord; and ate nothing save Communion her last 13 years. D. 1955. Fascinating! 120 pgs 29 photos;

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Alexandrina by Francis Johnston in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Denominations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Christian Denominations1

Early years

Lying in a trough of gently sloping, pine-wooded hills some seven miles east of the ocean resort of Povoa de Varzim, the village of Balasar consists of irregular clusters of small, rough stone houses, many of them gaudily painted, embracing a population in excess of 1,000 inhabitants. The surrounding countryside is dotted with little white cottages and crowded with vineyards and smallholdings yielding corn, vegetables, olives and figs. Bronze-faced peasants till the stony soil and herd flocks of sheep, goats and amber-coated oxen with lyre-shaped horns and carved yokes along dusty roads, past crumbling tower walls and innumerable trellises and tunnels of vines.

The hamlets and villages of this pleasant region are clustered around their ancient stone churches and Balasar is no exception. Rising on the lower slope of a small stream known as the Este, the parish church of St Eulalia stands like a granite sentinel over the straggling stone houses of Balasar and it was here on 2 April 1904 that Alexandrina Maria da Costa was baptised, having been born four days earlier on the Wednesday of Holy Week, the second child of devout, hard-working peasants.

Shortly after her birth her mother was widowed and Alexandrina grew up with her elder sister Deolinda in an atmosphere of rustic simplicity and piety. As a small child, she must have been fascinated by the colourful religious processions which wound through the village on great feast days and the frequent fairs and dances held in the cobbled market-square to the shrill sound of fifes and accordions and a kaleidoscope of floral blouses, twirling skirts and flashing earrings.

Her earliest memory was when she was three years old. As she lay in bed with her mother for the afternoon siesta, she noticed a small jar of pomade on a nearby table. Carefully, so as not to waken her mother, she reached out for the jar with inquisitive hands. At that moment, the sleeping woman roused herself and called Alexandrina. Taken by surprise, the child let the jar fall to the floor where it shattered to pieces. Losing her balance, Alexandrina toppled over, injuring the corner of her mouth. She carried the scar for the rest of her life.

Naturally, she shrieked with pain and would not be comforted. Her mother, Maria Anna, anxiously wiped the blood from her mouth and quickly ran her to the nearby chemist shop for a prescription, where a kindly assistant tried to calm the child with a bag of sweets. Alexandrina responded with yells, kicks and scratches. "That was my first misdemeanour", she wrote in her autobiography which she began dictating to Deolinda in 1940 at the request of her spiritual director, Fr Pinho, SJ.

As she grew older, she would wander, fascinated, through the ancient village church contemplating the beautiful statues of the saints, particularly that of Our Lady of the Rosary and St Joseph. Their rich costumes enchanted her and she dreamed of dressing in the same way. "Perhaps this was a manifestation of my vanity", she wryly commented later.

One day when she was about six, she was overjoyed to receive a little pair of wooden shoes from her mother. In a transport of happiness she danced into her room dressed in her best clothes, and putting on the shoes, strutted around the house like a peacock. Having tired of this, she knelt down on the pavement outside and proudly placed the shoes in front of her as women did in the churches of Portuguese villages in those days.

One of her most formative experiences was vividly described by her years later.

When our uncle died, Deolinda and I stayed with his family until the seventh day after his death, to assist at the Requiem Mass. One morning, I was asked to go and get some rice from a bag which was in the room where his body lay. When I reached the door, I was unable to muster up the courage to enter. I was frightened. So my grandmother had to get the rice. That same evening I was ordered to go and close the window of that room. As I reached the door, I felt my knees tremble again and was unable to enter. Then I said to myself, "I must fight it. I must overcome the fear." I opened the door and slowly walked into the room where my uncle lay. Since that day, I have been able to master my sense of fear.

Her inborn liveliness and sense of humour led her to become a gay tomboy, full of wit and laughter, though without compromising a budding spirituality which few suspected, judging from her spontaneous joviality. Witty phrases and lively jokes flowed from her laughing lips. Deolinda, who was more composed by nature, was nearly always the victim. One morning, Alexandrina pushed over the lid of a large box of bed-linens and screamed as if she had crushed her hand. Deolinda rushed to her aid in panic, to be met by a chortle of laughter. In church, she would furtively tie together the fringes of women's shawls as they listened attentively to the sermon. Outside after Mass, she would hide behind a low wall and throw stones at the people emerging from the church.

Gradually, her developing spirituality began to master her propensity for mischief. By the time of her first Communion at the age of seven, she had already acquired a deep love of the Blessed Sacrament, visiting the village church with unusual frequency and making spiritual Communions whenever she was unable to attend Mass. On Sundays, she loved to sing in the choir and participate in the parish catechism group. When an aunt suffering from cancer begged Alexandrina to pray for her, the child responded with such fervour and perseverance that the habit of prayer became entrenched in her young soul. She wrote later:

I always had a great respect for priests. Sometimes, when I used to sit on a doorstep at Povoa de Varzim and see priests walking by in the street . . . I used to stand with respect as they passed. They would take off their hats to me and say the customary "God bless you." I often noticed that people looked at me as I did this. Sometimes I sat there on purpose so that I could get up at the appropriate moment to show my veneration for priests.

When Alexandrina was nine, she went with Deolinda and a cousin to hear a sermon in a nearby village given by a famous preacher, Fr Emmanuel of the Holy Wounds. She made her first general confession to him and the three girls remained there all day to listen to the afternoon sermon. Having taken their seats at the side of the Sacred Heart altar, Alexandrina placed her wooden shoes between the columns of the balustrade and listened to the priest with rapt attention. She recalled:

At a certain point the priest invited us to descend in spirit to the place of eternal suffering – Hell. I was incapable of understanding the exact meaning of this invitation, and convinced that the priest was a saint, I thought he would actually take us down to Hell. I rebelled and said to myself, "I don't want to go to Hell. If the others want to go there, I'm staying behind." I immediately took hold of my wooden shoes and made ready to escape. When I noticed that nobody was moving, I quietened down a little, but I kept a tight hold of my wooden shoes.

Due to the restrictions of rural life in those days, Alexandrina had only eighteen months schooling before being sent to work on a farm at the age of nine. Though a strong, capable child, the heavy manual labour, shot through with incessant bad language, taxed her severely. When she was twelve, her employer tried to assault her. She fought back vigorously and somehow managed to drive him off with an unexplained force in her rosary-clenched fist.

After this serious incident she was promptly brought home. This gave her the opportunity to become a daily communicant and to renew her love and devotion to the Blessed Sacrament. But later that year she fell dangerously ill with typhoid. Her condition became critical; for several days she hovered on the brink of death. When her weeping mother gave her a crucifix to kiss, Alexandrina shook her head and murmured, "This is not what I want, but Jesus in the Eucharist."

She finally recovered and was sent to a sanatorium at Povoa de Varzim on the bracing Atlantic coast. But her health remained precarious, and when she returned to Balasar she was still a virtual invalid. This led her to take up sewing for a living and she settled down in the village learning to be a seamstress with her sister.

One day when she was fourteen, she heard that the father of one of her friends had been found dying. She hurried to where he was living alone and found him lying in a heap of rags. Filled with compassion, she ran back to her mother and borrowing soap, towels and bed-linen, restored a semblance of human dignity to the poor man. He lived on for another twelve days and Alexandrina remained with him until the end to comfort him and his grief-stricken daughter.

Shortly after, her role of good Samaritan was repeated. She recalled in her autobiography:

A neighbour warned us that an old lady was dying. My sister took her prayer-book and some holy water and left the house. I followed her with two of my sister's sewing pupils.

At the door was a niece of the sick woman who did not have the courage to assist her. Deolinda entered and began to read the prayers for the dying over the woman. I stood at her side and I noticed that the fringe of her shawl was trembling like a leaf. When she had finished reading the prayers the daughter entered, but the old lady breathed her last without recognising her.

Deolinda then took her leave, saying "I have done all I can; I have no more courage to stay on." On seeing the dead woman's daughter in anguish, I hadn't the heart to leave her alone. I decided to remain and help her to wash and lay out the body, which was covered with sores. The smell was dreadful . . . and I had the feeling that I was going to faint. I said nothing, however, but a woman who had joined us noticed my distress and went to get a twig of geranium so that I could smell it. I thanked her sincerely, but did not interrupt my work. I finally left, after the body of the dead woman had been arranged with dignity.

One day, while Alexandrina was praying alone in her house, she heard the door of the courtyard open and moments later, a man's voice demanded, "Open that door!" Recognising it as that of her former employer, and realising she had no means to lock herself in, she clutched her rosary in apprehension and waited for the man to enter. There was a succession of violent rattles as he hammered at the unlocked door. But it refused to open. After vainly trying to force his way inside, the exasperated man finally went off, leaving the shaken girl convinced that Our Lord and his mother had barred the way to protect her chastity.

2

Victim soul

Alexandrina might have remained in the undramatic capacity of a seamstress, buried away in the wild and beautiful Portuguese countryside, had not a fateful event occurred in March 1918 which utterly transformed her life.

While she was working one day in an upstairs room in her home with Deolinda and another girl, there was a sudden knock at the front door. Alexandrina peered through the window, and to her dismay saw three men standing outside, one of whom was her former employer again. A glance at their impassioned faces told her the worst. She locked the door of the room at once. The men broke into the house and began forcing open a trapdoor on the floor of the upstairs room.

The girls quickly moved a heavy sewing-machine over the trap door. Not to be thwarted so easily, the men pounded the door with clubs. The dry wood splintered, the sewing-machine toppled over. One by one, the men levered themselves into the room. Deolinda and her friend were seized and Alexandrina was cornered by a third man.

"Jesus help me!" she screamed, lashing out at him with her rosary. Like St Maria Goretti, she was ready to die rather than consent to the man's lust. Frantically, she looked round for a way of escape. Behind her was a window, thirteen feet above the hard ground. It was her one chance. Desperately she jumped.

The pain was shattering. Gritting her teeth and wiping the blood from her face, she seized a stout piece of wood and staggered back into the house to defend her companions. Several well-aimed blows were enough. The startled men took to their heels, bruised and shaken by her courageous counter-attack. Fortunately, the other two girls were unmolested.

The thirteen-foot high window from which Alexandrina jumped in order to escape from a man who had come to molest her. This event occurred when Alexandrina was fourteen years old; it resulted in a spinal injury which eventually led to total paralysis at the age of twenty.

The da Costa home, where the bedridden Alexandrina was confined to a tiny upstairs room.

But Alexandrina's spine had been irreparably injured. Long months of increasing pain, incapacity and depression followed, though she never yielded to despair. In 1923 a specialist from Oporto, Dr Joao de Almeida, confirmed the family's worst fears. Total paralysis set in and on 14 April 1924 she became bedridden for life.

The awful predicament clutched at her heart and severely tested her faith and courage. Confined to a tiny upstairs room in an obscure house hidden from the outside world by a high stone wall was tantamount to being buried alive. Fortunately she had already practised the virtue of detachment; her only desire being for flowers and for the church. Deolinda settled down to become her nurse and secretary while their mother worked to earn money for food. "I had moments of discouragement," Alexandrina says of this period, "but never one of despair." When there were singing lessons in the church, the two sisters became sad, one because she had to leave her charge and the other because she could not go. But the crippled heroine conformed very quickly to the will of God and regarded her bed as "my beloved cross".

At first, she tried to distract herself by inviting friends in for a game of cards. But the novelty soon wore off and she resolved to try to storm heaven for a cure. She promised to give away everything she had, to dress herself in mourning for the rest of her life, to cut off her hair, if only she was cured. Her anguished family and cousins joined in the assault on heaven, but the paralysis stayed.

Worse still, her condition began to deteriorate until the slightest movement caused her agonising pain. Once again she hovered on the brink of death, and the last sacraments were administered several times. The medicine she took had no effect, except to soothe and calm her. Looking back at this distressing period she wrote later that "I would have done better to have stayed united to Jesus because he alone is the true life and the true joy."

Every evening the Costa family gathered round her bed and lighting two candles before the statue of Our Lady, recited the rosary on their knees, followed by night prayers. During the day, whenever there were no companions to distract her, Alexandrina would meditate, pray and weep, imploring Our Lady to heal her. Sadly, she would sing the Tantum Ergo as in church, and not having the blessing of Benediction, she would ask Jesus for it from heaven, "and from all the tabernacles in the world". The parish priest lent her a statue of the Immaculate Heart of Mary for the month of May, and afterwards Alexandrina scraped together every penny she could to buy a similar statue of her own. In time, this statue was almost kissed smooth.

Her growing love of prayer led her to abandon her innocent distractions. She began to long for a life of union with Jesus. This union, she perceived, could only be realised by bearing her illness and incapacity for love of him. The idea of suffering being her vocation suddenly dawned on her. Without knowing how, she offered herself to God as a victim soul for the conversion of sinners.

In 1928, a local pilgrimage to Fatima was organised and Alexandrina implored Our Lady to let her accompany them. The fast-growing shrine was already a magnet for hundreds of thousands on the thirteenth of each month from May to October, and the numerous miracles occurring there gave the sick woman a surge of hope. But the doctor and parish priest were adamantly opposed to the idea. How could she be conveyed some 200 miles, they argued, if to touch or turn her caused her unspeakable suffering?

In the face of their inflexible stand, Alexandrina brokenly closed her eye...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- Contents

- DECLARATION

- Prologue

- 1 Early years

- 2 Victim soul

- 3 Ascent to Calvary

- 4 Years of torment

- 5 Ecstasies of the Passion

- 6 The Eucharist alone

- 7 Medical confirmation

- 8 Seraph of love

- 9 Who will sing with the angels?