eBook - ePub

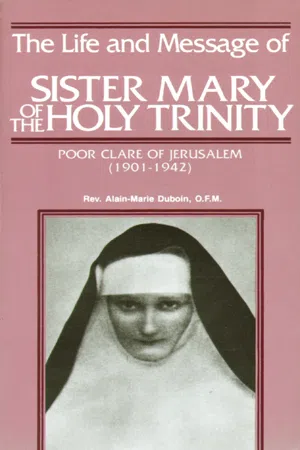

The Life and Message of Sister Mary of The Holy Trinity

Poor Clare of Jerusalem (1901-1942)

- 254 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Life and Message of Sister Mary of The Holy Trinity

Poor Clare of Jerusalem (1901-1942)

About this book

Life story of Louisa Jaques (1901-1942), author of Spiritual Legacy of Sr. Mary of the Holy Trinity, a Poor Clare of Jerusalem, to whom Our Lord gave messages about the love of His Heart for souls. Her Protestant childhood and youth in Switzerland, religious and philosophical yearnings, great love for her family, guilty friendship with a young married doctor, conversion, vocation and early death. 22 pictures. Plus messages from Our Lord (from The Spiritual Legacy), arranged by topic. Includes an article on the Poor Clares of Rockford, Illinois, with 31 photographs of the nuns.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Life and Message of Sister Mary of The Holy Trinity by Alain-Marie Duboin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Denominations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Christian Denominations— Part One —

THE LIFE

— 1 —

CHILDHOOD AND YOUTH

(1901 -1926)

(1901 -1926)

Louisa Jaques was born in Pretoria, in the Transvaal, South Africa, on April 26, 1901. Her father, Numa Jaques, was a Protestant minister. With his wife, he ran a post of the "Swiss Mission." Both of them originally came from the Jura mountains in the canton of Vaud, Switzerland.

The mountains and forests of their birthplace had forged their characters. The Jura is an austere region, winter there is long and rough, and the population is hard-working. To supplement the insufficient income from agriculture, a local industry had been born generations before. Shops, or little factories, produced pieces for clock-making and precision machines. Hence the natives of the Jura acquired an acute sense of exact and minute work and a lofty professional conscience.

The Protestant Reformation, imposed on the region by the victory of Bern, found there favorable ground to welcome the strictest Calvinist doctrine. The liberal tendencies of the 19th century scarcely took hold on these parishes. Rather, the faithful turned toward movements of religious awakening or toward sects in order to defend their faith and maintain a demanding morality. Their mentality remained very distant from the Catholic religion.

At the time he was a young worker in a factory at L'Auberson, Louisa's father felt the missionary vocation well up in him while he was listening to a sermon. It was an irresistible call. Fighting opposition from many sides, he had to earn the money necessary for his preparatory studies. No obstacle stopped him, and he successfully finished his missionary formation at Lausanne.

His wife-to-be, whose maiden name was Elisa Bornand, showed the same aims of apostleship. With ardent piety, she rose early every morning to read the Bible and to pray. She became engaged to Mr. Jaques soon after his return from Lausanne, but refused to marry him before being certain they would be able to go to the missions. The French-speaking mission to which her fiance belonged was, in fact, slow in assigning to him the post where he was to exercise his ministry.

After the oldest child, Alexander, then two daughters, Elizabeth and Alice, Louisa was the fourth child in this household. More than the others, she inherited her mother's character: determined and energetic, firm in her principles.

Her birth, alas, did not bring all the joy that they had anticipated. The Boer War was going on and the country was enduring a period of alarming drought. The double burden of the Mission and the family was heavy. The arrival of a girl disappointed the parents who had hoped for a boy. Madame Jaques had dreamt of a son with a tempered character who would have a brilliant career. A few hours after Louisa's birth, this courageous mother was carried off by a sudden illness. She was 36. Before dying, she took the newborn child in her arms and said, "We will love her dearly just the same."

Later, during the stay in the Transvaal, when Louisa inquired about her mother among some old blacks, the family's servants, her joy was great on hearing that they remembered her mother's piety: she was "the woman who prayed." The death of Madame Jaques so soon after the birth of the child deprived the latter of maternal tenderness. At the same time, this catastrophe plunged the father into dismay. The baby, scarcely arrived in the world, suffered from involuntary abandonment. Illness struck other members of the Mission. All their efforts were aimed at driving death away, and they forgot to welcome the life which had just blossomed out.

Soon, however, overcoming his grief, the father carried over to the little Louisa the affection he had had for his spouse. From then on, she was the object of a special attachment.

After the death of Louisa in Jerusalem, Mr. Jaques wrote to the Mother Abbess that the child had been offered to God even before her birth.

Providence watched over the little orphan. Her Aunt Alice, who had helped Madame Jaques on her deathbed, had been living in the house for nearly two years. A cultivated person, she had spent several years in England as assistant directress of a boarding school for girls. She had planned to go back to Switzerland and open her own boarding school with a friend, but before that, she had wanted to visit her sister in Africa. She arrived there just in time to be godmother of the third child, a girl to whom they gave the name of Alice. The war obliged her to prolong her stay, and after the death of her sister, she generously devoted her time to raising the orphans.

In 1902, with the war over, Mr. Jaques resolved to take his children to Switzerland, hoping to improve their health. During the siege of Pretoria, they had suffered from malnutrition; Louisa's health was particularly affected. They left Pretoria on June 4, 1902, and arrived in Switzerland in the beginning of July. Aunt Alice, whom the children would call their "Little Mother" henceforth, was with them. The family settled first in L'Auberson, at the house of the maternal grandmother. At the end of autumn in 1903, they moved to Morges on the shore of Lake Leman (or Lake of Geneva).

On May 1, 1904, his holiday ended, Mr. Jaques went back to his Mission, bringing with him his oldest child, Alexander. Aunt Alice, giving up her plans for a boarding school, devoted herself, along with her younger sister, Rosa, to raising the motherless girls.

Years later, after the death of Sister Mary of the Trinity, her sister Alice frankly admitted: "I wonder if some blame didn't weigh on Louisa's childhood. It is true that age is without pity! And I would believe that perhaps we, her older siblings, had the cruelty to reproach her for her sad coming into the world. Louisa was born during the passage of a comet. We had the habit of reminding her that the little Negroes who were born the same day as she had been thrown to the crocodiles. It seems to me that her birthdays, on April 26, were celebrated with a mixture of sadness."

The sight of the coffin next to the cradle had overshadowed the dawn of this life.

"Little Louisa is a very good baby who scarcely ever cries, either day or night," Aunt Alice noted in 1902 when the family settled in Switzerland. The child was surrounded with all possible care. In spite of that, her frail constitution suffered from the Swiss climate. The very first winter, she contracted pleurisy from which she kept a stubborn cough and chronic bronchitis. Several times during her childhood, she had pulmonary congestion. All that in spite of the attentive care of "Little Mother," who dressed her in woolens in every season and, for fear of her getting a chill, did not permit her to go play outside with the other children. Louisa's sprightly and lively nature suffered greatly from this constant privation of the pleasures given her older sisters.

She became a very alert little girl with decided gestures. With her observing looks, she followed all the gestures of her sisters, their attitudes, their movements, without imitating them, however. The independence of her character was manifesting itself already.

Her sister Alice, who would always remain the closest to Louisa, gave this testimony about her: "Louisa always had a good and generous character. While she was still a child, we already considered her the angel of the family . . . Although she was younger, I always felt that she was superior to me. It is as if, while still little, she knew how to read the souls of people. Therefore, 'Little Mother,' who was not perfect, feared Louisa a little. Although she was very sensitive, Louisa did not cry easily. I remember seeing her cry only a few times, but how much more concentrated were the tears which flowed then."

Between the two aunts, there was 15 years difference. Rosa, the younger, sometimes suffered from the authoritarianism of her older sister. The good heart of Louisa understood, and she showed Rosa more affection than did any of her other sisters, trying in this fashion to make her life more agreeable.

Aunt Alice devoted an attentive solicitude to the religious formation of her nieces. During her entire childhood, Louisa faithfully recited her prayers each evening, no matter what the hour at which the children went to bed and despite the somewhat annoyed reproaches of her older sisters.

Aunt Alice's religious discipline was severe. Each day, at the end of the meal, the children had a family ritual of prayers and readings. One day, a young cousin was at the house. She was four years old and Louisa was 14. Finding the time dragging, the child covered her nose with some tin foil and was having fun peeping over it. Louisa could not stifle an outburst of laughter, which amused her sisters: everyone broke out laughing. Indignant, Aunt Alice ordered Louisa to leave the table and go outside.

In good years as in bad, the two aunts with the children went up to L'Auberson, to the old home of their grandparents for the summer vacation. One Sunday morning, the three little girls were at church with "Little Mother" in their habitual place, the third pew from the front on the left side of the nave. Suddenly Aunt Alice was distracted from the sermon by the appearance of Louisa, who, red enough to burst, seemed on the point of smothering. She hurried to take her by the hand and to leave the church with her. The poor child—she was not yet 10 years old—was holding herself back with all her might. She did not dare cough in church!

Very soon, Louisa learned to be of service and to devote herself to others. When there were errands to run, "Little Mother" told the oldest girl to do it. The latter passed the errand on to the second one, who foisted it off on the youngest. Louisa performed it with good humor. For her, to be of service was the most natural thing in the world. She did not know what it was to pout. "Louisa," wrote her sister Alice, "didn't know what bad humor was, neither as a child nor later. Bad humor makes others suffer. Louisa never did that."

Close-mouthed and meditative, Louisa manifested from childhood a profound aspiration for the beautiful, the perfect. This desire for perfection, always unsatisfied, was shown in the thoughtfulness of her behavior, in the affability of her manners. She suffered from not being able to communicate better this need, to have this desire shared. Therefore she often felt misunderstood and isolated.

Absentmindedness was her principal fault. She grieved over it during her entire life. Must we explain it by her isolation? "She was often distracted," noted her sister Alice, "absorbed in her reflections and completely absent from what was going on around her."

With Louisa, "Little Mother" found again her vocation as a teacher. While watching over the ever-precarious health of her niece, she taught her to read and prepared her for life at school with more success than with the older sisters. It is true that a lesson given by Aunt Alice demanded fixed immobility and unfailing attention. The lack of discipline of the older sisters had worn down her patience.

While Louisa showed herself to be more studious, she also occasionally wanted to play truant. One day, she hid her alphabet and primer books. Neither the reasoned lectures of "Little Mother" nor the fruitless searches of her sisters under the furniture succeeded in shaking her resolve. She remained imperturbable in her decision to take a vacation that day.

As soon as she knew how to talk, Louisa related to her older sisters stories which she made up. "Little Mother" gave her a thick notebook covered with black artcloth to write down all her tales. Louisa accomplished this task with joy; she took great care in keeping this notebook. At that time, she was between five and six years old. Not knowing how to spell, she wrote phonetically. All of it was her own invention; neither collaboration nor advice were given her. She illustrated the stories with pictures cut from the newspaper; adventures where the people, animals and flowers spoke equally. Each story ended with a little moral in the fashion of La Fontaine's fables. This collection was the joy of her sisters. They browsed through the stories in order to read the conclusions, which always greatly amused them.

As soon as she entered school, Louisa set aside her notebook of stories once and for all. Well prepared by her aunt, she made rapid progress in school.

She completed the several stages of education in private institutions. The college which she went to could only give a private degree. Later she had to go to a state teacher's college in order to obtain the certificate required for teaching in parish schools.

In Switzerland, neutral and protected, the declaration of war in 1914 scarcely troubled the Jaques family living in Morges. They reckoned with the sufferings in neighboring countries, which they tried to alleviate by participating in projects to assist prisoners and the seriously wounded.

In February, 1915, Louisa experienced her first great sorrow.

She lost her music teacher, who died suddenly at the age of 36 after an apparently minor operation. Louisa felt a strong admiration for this woman, to whom she had become profoundly attached, and who also admired her. The tragic news was announced too brusquely by a visitor. Louisa remained silent with grief, then she ran into her bedroom and, on her knees in front of her bed, sobbed for a long time, her head under the covers. She kept as a treasure a gift that the teacher had made to her: a little book of religious thoughts which she read every evening, without fail, before going to sleep.

Not long before the war, her brother, Alexander, the oldest child of the family, had come back from Africa to study theology at Lausanne. The three sisters and their brother spent their summer vacations together in L'Auberson. In 1916, they took advantage of particularly favorable weather to make numerous trips in the mountains. The fatigue was too much for Louisa, who developed a fever. At the end of vacation time, they kept her at L'Auberson until she regained her health. She returned to Morges in November for her last year of courses and obtained her diploma in the beginning of the summer of 1917. Louisa planned to study at the university, and with this purpose in mind, began to prepare for the federal entrance examination. Her family opposed the idea, however, because of her frail health. This was a great sacrifice for Louisa, but the thirst for learning did not abandon her.

Vacation time that year was clouded by another trial, the death of Aunt Rosa. More reserved than her older sister, very devoted, very pious, too—she belonged to the Salvation Army—with her presence she tempered the austerity of family life. Aunt Rosa died prematurely after months of painful struggling against the cancer that finally carried her off.

After a few weeks of rest at L'Auberson, Louisa went back to Morges. There she found her first job. She was engaged as a private...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- CONTENTS

- Introduction

- Author's Note

- — Part One — THE LIFE

- — Part Two — THE MESSAGE

- Appendix: "Hidden Goodness: Rockford's Poor Clares"