- 631 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

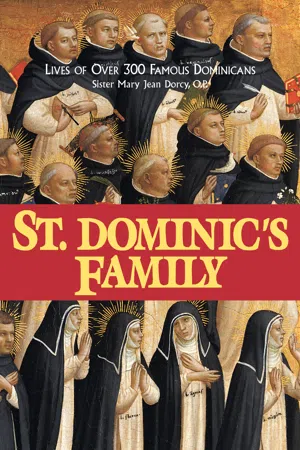

About this book

A monumental work. Some 335 biographies of the most famous people of the Dominican Order—priests, nuns and Third Order members—from St. Dominic himself (1170-1221) to Gerald Vann (1906-1963), arranged century by century. Great stories of heroes and heroines of Christ—miracles, visions, martyrdoms. Belongs in every Catholic home—imagine, over 300 saints' stories in one volume! Impr. 631 pgs,

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access St. Dominic's Family by Sr. Mary Jean Dorcy, O.P. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Denominations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Christian DenominationsSEVENTEENTH CENTURY

VENERABLE ROBERT NUTTER

(d. 1600)

Most candidates coming into religion have at least the advantage of a personal interview with some member of the Order they wish to join, and have the opportunity of discussing its ideals and aims in reasonable leisure before committing themselves. Robert Nutter applied by mail for membership to an Order he know only by hearsay, because Dominicans were banned from his unhappy country at the time. To make it more interesting, there is evidence that he made this request at a time when he himself was in jail awaiting sentence, and the letter was smuggled out by friends.

Robert Nutter was born in Lancashire, around 1555, of a wealthy family which usually sent its sons to Oxford. However, when Robert and his brother were of college age, both wished to be priests. The Church in England was suffering fire and the sword, so the two young men were smuggled out across the channel to the English college at Rheims. Robert was ordained there in 1581.

Young men who studied abroad for the priesthood were marked for death if they returned to England. This did not daunt Robert and his companion, a Father Haydock, as they planned their trip home. Both of them expected to be martyred; indeed, that was part of the priesthood those days in England. Three weeks after ordination, the two young men, disguised, and using forged names and passports, returned to their country and set about the work for which they had been ordained. Robert stayed clear of the law for two years. Then he was captured and put in the Tower. Here he was tortured in several ways. One instrument of torture employed was a device called "the scavenger's daughter"; even without knowing exactly what it was, one wonders how a man could emerge from such treatment and go right back to his dangerous job again.

Robert was released from the Tower—after being presented with a bill for food and candles—and, with twenty other priests, was put on board a ship for banishment. Even though they made a loud English clamor at the injustice of being sentenced without a trial (a detail that would never have bothered a Continental), they were shipped off to Normandy and threatened with immediate death if they returned.

By 1586, Father Nutter was back in England, refreshed and full of new ideas. However, the vigilance had tightened up, and he was taken prisoner in a short time. He began a long stint at Newgate prison, one of the more infamous. After a few years, he and a number of other priests were transferred to an island prison.

Here the life was severe and lonely and frustrating, but not as desperate as it had been at Newgate. The place was not so filthy, and there was no torture. Father Nutter pointed out that many monks lived as austerely, and he, with several other of the more fervent, set up a rule of life, trying to follow a sort of monastic routine. It was during this time, if the tradition is correct, that he wrote to the French Dominican provincial and begged to be admitted to the Order as a Tertiary.

After sixteen years of prison Robert Nutter and several other priests escaped and made their way to Lancashire. One account of his life proposes that at this time he met a Dominican priest, who formally received him into the Order. We do not know. There was pitifully little time to do anything, for he was captured with three other priests at Lincoln, and the death sentence was immediately carried out.

The tradition of the sanctity of Robert Nutter, like that of the other English martyr priests, was kept by the faithful during the years of persecution. His cause was formally opened in 1929, along with that of many other priests, mostly Jesuits.

Thomas Hesketh, Attorney of the Court of Wards, and a notorious priest-chaser, wrote a curiously-spelled account of Robert Nutter in a letter to his superior officer. It gives us a vivid picture:

It appeared that the true name of one of the priestes was Robert Nutter, born in Lancashire, he departed owt of England XXIJte yeares past & after that he had bene Scholler at Rames & at Rome he was made Priest by the Busshop of Laon & then Retorned into England, before the Statute made in the XXVIJ yeare of her MAties Reigne, And was then apprehended & Banisshed. And after that havinge an Intencon to go out of ffraunce into Scotland he was taken uppon the Seas in a ffrench Shipp by Captain Burrowes & Browght into England where he Remained in Wisbich & other prisoners XJ yeares. And uppon the mondaie before Palmesondaie Last he escaped owt of Wisbich the gate beinge left open by the Porter. He wolde not Confesse wher the Porter was nor what became of him. He confessed that he was a Professed ffryar of the Order of St. dominicke duringe the tyme he was prisoner in Wisbich, where in the presence of dyver priestes he did take his vowe the wche was certified to the Provinciall of the Order at Lisbon & by him allowed . . . Your honor maie easilie discerne, and so did al men as I thincke that were at the execucon, what notable traytors these kynd of peopele are, ffor not withstanding all their Glorious Speeches yett their Opinion & their doctrine is, that her highness is but tenant at will of her crowne to the Pope . . .

MARY RAZZI

(1552-1600)

The extraordinary career of Mary Razzi should convince us, among other things, that God likes variety among his creatures, and that sanctity is never to be by-passed for a mere matter of circumstances.

Mary Razzi was born on the Greek island of Chios, in 1552. Her father was a wealthy Genoese, her mother a Greek. The little girl was baptized in the church of St. Dominic, and began to show signs of unusual spiritual gifts very early in life. She had firmly made up her mind to enter a convent, but when she reached the age of twelve she was dismayed to discover that her parents had already arranged a marriage for her. A stormy year followed, in which Mary did everything in her power to avoid the marriage. However, her most vigorous efforts were of no use, and she was finally forced into the unwelcome union.

The chronology here is a little vague. Since Mary was left, at eighteen, a widow with two children and two had died, she must have married at thirteen or fourteen. Of her husband we have no information, except that he was captured and killed by the Turks as he and his family were fleeing Chios. Mary, who had suffered the indignities of Christian slavery under the conquering Turks, was moved to flight when she heard that the Grand Vizier was planning to take her two little boys away from her and train them as Moslems. She, her husband and children, fled on a small ship which was overtaken by pirates in the Straits of Messina. The helpless young wife stood by, sheltering her two tiny boys, and saw her husband slaughtered by the Turks. Then, through some twist of fortune, she was set ashore unhurt.

The widow arrived in Sicily terrified. The sole support of two babies, she was unable to speak the language and was a complete stranger to all the customs. She was only eighteen years old, very pretty, and there were many people who felt that another marriage–almost any sort of marriage—would solve her difficulties. Mary disagreed. Her parents had forced her into marriage. Now she was determined to consecrate herself to the service of God.

She placed her two little boys, Basil and Nicholas, with kindly people who would give them a home; she could see them occasionally. Both of her boys would one day become Dominicans, so it is evident that they were given a good education by their foster parents. Mary herself went to the Dominican church and asked for the Third Order habit. She received it, after some time, in a public ceremony in Messina. After this, she retired into a little room that someone had offered her. It was in one of the large homes near the Dominican church. Here, for fourteen years, she prayed almost uninterruptedly. Her reputation for sanctity was very great, and people of all classes came to her for advice and prayers.

When her second son was sent to Rome for his studies, Mary's older son was already a Dominican student at the Minerva. Mary decided it would be a rare opportunity to see Rome and to be near her sons, so she obtained permission to travel with her son. They took passage on a ship, and it was barely out of sight of land when they were horrified to see a Turkish ship bearing down upon them. Mary knew all too well what cruelty was represented by that slanted sail. She dropped to her knees and begged God to spare them. As they watched, the Turkish ship altered its course, going away without bothering them.

In Rome, a kindly family named Marini took her in, and she resumed her life of prayer and penance. She lived in perpetual abstinence, fasting most of the time, and she slept, if at all, on boards. She seemed hardly to use any time for the needs of physical life, but to spend her energies in heavenly conversations. Her little room was lighted up by the heavenly glow of her distinguished visitors: Our Lord and His Blessed Mother, St. Dominic, St. Hyacinth, St. Catherine of Siena, and shining troops of angels. The devil came, too, under horrible shapes—once as a tiger, other times as a large snake—and sometimes threw her around and beat her. She emerged from these bouts badly battered and bleeding, but victorious.

Outwardly, Mary's life was quiet. She lived in the neighborhood of the Minerva, where she went to Mass, and where her two sons were stationed. Several times a week she went to the public hospitals to help care for the patients, and she always saved the food that was given her for the sick poor. People in trouble would seek her out in her little room, or when she was praying in the Minerva. One day a young man who had resolved to commit suicide came up to her as she was praying and explained what he was going to do. She talked with him for awhile, convinced him to go to confession, and then reached under her scapular and took out a number of gold coins. "This will tide you over until you get back to your people," she told him. How did the gold coins happen to be there? She did not know. But whenever she needed money for anyone who was in trouble she always found it in some unlikely place.

On Pentecost Sunday, 1593, while making her thanksgiving after Communion in the church of the Minerva, she was overwhelmed with pain. It centered in her head, and it was so excruciating that she fainted. She realized that she had been given the stigmata of the crown of thorns. On a later occasion, she had a vision of our Lord bound to the column of the scourging. At this time she received several of the other wounds. She bore these marks of divine favor until her death, but she was so reticent that no one of her companions knew the full extent of her stigmata.

One time, when she was attending Compline at the Church of the Minerva, she saw the Blessed Virgin going up and down the aisle, blessing the brethren. Several times she saw angels walking in the Salve procession. These "happier" visions she revealed, but she kept the sorrowful ones to herself.

There is evidence that Mary was not very talented as a babysitter. She was left one day with little Vincent Marini, the baby of the family who had been so kind to her. She put him down on the bed and gave him a nut to play with. Naturally, he swallowed it. Mary, coming in a few minutes later, discovered that the baby had choked to death. She knew only one way to handle such a situation; she began to pray. Soon the baby coughed up the nut, and began crying in a robust manner. The child died a few days later, and he returned in a vision to thank her for her care of him. Some years later she had a vision in which she saw St. Catherine of Siena and little Vincent, shining with heavenly light.

Mary seems to have had what the missal calls the "gift of tears." Hardly an event of her life is recorded without the remark that she wept copiously over it. She shed many tears—rather futilely, one would be inclined to say—for having been married. But, fortunately, most of her tears were shed for the practical reason of man's ingratitude to God.

Mary had one interesting gift that should make her the envy of every harrassed superior in the world—she could make herself invisible. If she wanted to hear a sermon without having the preacher know she was there, she merely made herself invisible. Sometimes, when in line for confession in the church, and finding that she was not ready to go in, she became invisible, letting everyone else go ahead—a truly fascinating gift.

Mary Razzi died in 1600, and no less a person than St. Charles Borromeo remarked that he was sure she was a saint.

DOMINIC BAÑEZ

(1528-1604)

Dominic Bañez, a famous theologian, was the staunch defender of Teresa of Jesus, at a time when the great reformer of Avila badly needed defense.

Dominic Bañez was born in Valladolid in 1528. His mother was Spanish, his father Basque. Being a superior student, he was sent to the University of Salamanca, where he met the Dominicans. He studied under Melchior Cano and Dominic Soto, and continued under these great masters after he had entered the Order, at St. Stephen's, in Salamanca. Under such excellent teachers he made great strides in sacred science, and, occasionally, even as a student, he was called to fill in for an absent professor. By the time he had acquired his degree he was already well known. He taught at Avila, Valladolid, and Alcalá. It was when he arrived to take the assignment at Avila that he met the force that was Teresa.

The young Dominican professor did not know anything about Teresa when he came to Avila; absorbed in getting his doctorate at Salamanca, he had heard little gossip. When he arrived in Avila, it was to find the whole town in a turmoil; he followed the crowd to the city hall and listened while the governor delivered an impassioned oration about "closing down the monastery and driving the women out of town." Even the bishop spoke up, saying that the situation was intolerable. Dominic enquired around until he knew what the trouble was: Teresa and three other pious women wanted to start a monastery of strict observance. At a pause for breath, the stranger stood up, and a ripple went through the audience: "Here is the new doctor from Salamanca—hear, hear."

"I have never seen Doña Teresa," he said, "and I am therefore not at all prejudiced. I should have imagined from the amount of excitement that the Moors were back at our gates. I find it is only that four poor women wish to live a life of self-denial and prayer, and that you want to stop them from doing it. Just because it is new, do you therefore feel that it must be condemned? In every religious order, was there not a time at its birth into the Church when it was new? When our Lord founded the Church, wasn't it new? Trees putting forth new leaves are doing nothing novel. If these women are establishing a reform, they should be protected and helped. I find it hard to believe that a few poor women, living in poverty and praying for us, could be a menace. Have we plague? Fire? The Moors? Let us find a foe more worthy of Avila than a poor little convent that cannot defend itself."

Strangely enough, the shouting crowd quieted down and began to drift away. Men who had torches in their hands with which to set fire to the house of Doña Teresa, hurriedly slunk off, and officials hastily tried to change the subject. Teresa's project was saved. When the news was brought to her in the little convent where she had entrenched herself, she begged the messenger to go and get Father Bañez so that she could see him and thank him. "He alone is responsible for saving our beginnings," she claimed afterwards.

Father Bañez took a deep interest in the affairs of the Carmelites, and he was confessor and advisor to Teresa for some years. His combination of learning and holiness appealed to the great reformer; she was often plagued with stupid people, and she probably found it refreshing to deal with intelligent ones. Under the direction of Father Bañez, she wrote her Way of Perfection, her Book of Foundations, and her Third Book of Revelations.

In 1577, Dominic Bañez returned to Salamanca and a few years later was occupying the chair of theology there. When the master general ordered him to publish his theological works, he set about the gigantic task. He had been writing for years, and his commentaries on St. Thomas were published with painstaking care; he himself read and corrected all the proofs.

After a long and distinguished career as Spain's celebrated theologian, Dominic Bañez died in his native city in 1604.

THE MARTYRS OF GUADALUPE

(d. 1604)

The six Dominicans who were killed by the Indians on the island of Guadalupe, in the Caribbean, in 1604, are listed as martyrs, though it would be a little difficult to prove whether they did or did not die "in odium fidei."

The six men—John of Moratella, Vincent Palau, John Martinez, John Cano, Hyacinth Cistenez, and Peter Moreno—were part of a band of missionaries en route to Manila with the Philippine provi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- PREFACE

- CONTENTS

- THIRTEENTH CENTURY

- FOURTEENTH CENTURY

- FIFTEENTH CENTURY

- SIXTEENTH CENTURY

- SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

- EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- NINETEENTH CENTURY

- TWENTIETH CENTURY