- 502 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book is pivotal to understanding Mexico! Shows how Catholic Spain during 300 years--1521-1821--formed Mexico and made her prosperous and happy, but how the great Masonic Revolution (1821-1928) has made her poor and miserable. Shows that Mexico is still basically Catholic (97%) but is ruled by an anti-Catholic government. Full of insights and crucial to understanding Mexico.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

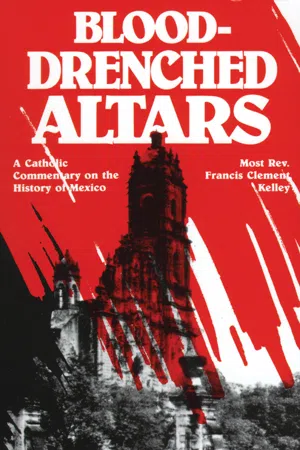

Yes, you can access Blood-Drenched Altars by Francis Kelly in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Denominations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Christian DenominationsSTUDY AND NARRATIVE

I

INTRODUCTION

THE UNITED STATES of America is situated geographically between two potentially great and wealthy neighbors, Canada and Mexico. The first is still loosely bound to Europe through its membership in the British Family of Nations; the second is nominally a free Republic. Both have agricultural and mining resources of great value. Both potentially are competitors with the United States for world markets. Both, but especially Canada, are excellent customers for American industrial products. With both, nevertheless, we are on official terms of friendship. Our friendship for Canada is more than official. As to Mexico there is reason for doubt. We know that many, if not the great majority of Mexicans, dislike, to put it mildly, their Northern neighbor. Americans themselves do not dislike Mexicans. The feeling is as yet only half-formed but it is a mixture of suspicion, pity, and in many cases even half-veiled contempt. Mexico is looked upon popularly as a country of ignorant people who have never found themselves; quarrelsome, petulant, unreliable, and unstable; a people with whom it is impossible to maintain ordinary decent relations; a people with a history of violence scarcely relieved by a few favorable contrasts; a nation of robbers on the one hand and beggars on the other, unenlightened and, for the most part, miserable.

The difference of language scarcely enters into the question. Canada is a bilingual country. English and French are spoken in its Parliament and Senate. A very large part of its people speak French as their maternal tongue and it is this part which is of greater interest to us because it is so "romantically different." The question of religion might play a more important role, for more than one third of Canada's people are Catholics. Its greatest province is predominantly Catholic, but with a Protestant minority justly content, having their own institutions of worship, education, and charity. That province, Quebec, is, perhaps, the outstanding example of mutual religious understanding and peace in the whole world. Americans admire and praise it. But they have failed to note the contrast with Mexico. Mexico has a very small Protestant population, for the most part made up of its American and British residents. They are not permitted to possess a place of worship of their own, nor to teach in a school. They may not employ a Protestant clergyman of their own nationality to preach to or pray for and with them. Religious toleration joined to good-will in one part of Canada is from Protestants to Catholics. In the other it is from Catholics to Protestants. In general both are quite satisfied with the situation, especially the Protestants of Quebec. In Mexico, predominantly Catholic, the intolerance is for Catholics as well as Protestants, but for it Catholics are in no way responsible. They hate and abhor it. They would gladly accept the Canadian situation for all. The persecutor in Mexico is the Radical, who hates the Protestant less than the Catholic only because there are fewer of him.

Since the War of 1812 with Great Britain, the thought of bringing Canada into the United States has never been even considered seriously. To the overwhelming majority of Americans and Canadians the idea is one of the unthinkable things. Nor has either country ever had a dispute that peaceful arbitration could not, and did not, settle. The two countries have traded and bartered, visited and chatted together, for far more than a century, all in good will and with even no little jollity. It never occurs to Americans to call Canadians, English or French, an ignorant, suspicious, pitiful, petulant, unreliable, or unstable people. A thought abhorrent to even the most warlike of Americans would be to quarrel with Canada and Canadians.

With Mexico it is different. Americans have been at war with Mexicans. The United States has invaded Mexico. Mexican soldiers have raided and killed American soldiers on American soil.1 American armies have camped on and crossed the Mexican border. The American Navy has bombarded Mexican cities. Worse than all, Americans have never, during all the years of their existence as a nation, ceased to fear the possibility of a bloody encounter with their Mexican neighbors.

Who are these neighbors? By far the greater part are a very kind, a very peaceful, even a very lovable people. Americans who live or have lived among them have nothing but praise for their hospitality, their politeness, their honesty, and their good-will; that is, for all those quite admirable traits and virtues as they are found in the poor—and in Mexico the poor are the major part of the population. These traits and virtues are found also among many, even the majority, of the upper classes. What Americans hate in Mexicans, is, strangely enough, found only in that class which, politically and socially, we take for the only Mexicans worth dealing with, the only ones as a matter of fact we have dealt with and listened to. The grace of God made the Mexican people, as a people, much to be admired. But we do not deal with them. Officially, and often unofficially, we do not know them. We accept what the others say against them. We have been doing that for well over a century.

Is it that we fear a prosperous Mexico as a neighbor? I do not think so. Certainly we are always glad to hear of the prosperity of Canada. Do we really want Mexico to have peace? I think we do. We certainly want Canada to have and keep it. We are a business people and know that the prosperity of our neighbors can bring only good to us by an interchange of the things we have or want for the things they have or want. There is nothing for us to fight about, and everything to keep us all in peaceful relations with one another. Poverty and strife in one, mean short markets and bitter words in the other.

What fate has doomed the people of the United States and the people of Mexico to be as they are to each other? It is not fate but plain ignorance, and alas! very much on our own side. We do not know the truth about Mexico, the story of her triumphs, her defeats, her beating onward against the winds of adversity. We have listened to slanders against her. We have believed the lies of the riffraff from within who robbed her. We have helped them in their robberies. In a word, we have treated Mexico not at all as we have treated Canada, for we have hurt her. The worst ill feeling always comes from the one who has done an injustice to the other.

It goes without saying that no one can read history to his or her own profit with a mind full of unconquerable prejudices. In other days, that was how history was written, and it is the reason why it could and was truthfully said that history is nothing but a recorded lie. Modern research is rapidly changing all that. Prejudice is being taken out of historical writing. It will be a more difficult task to take it out of reading. Nevertheless that too must be done. For what civilization is going to be will, to a greater extent than we now realize, perhaps, depend on what we learn of its mistakes as well as its triumphs. No history written in the English language has more need to be approached without prejudice than that of Mexico. Too much of the English record called Mexican history is the work of conscious or unconscious special pleaders.2 We shall notice these as we go along. The present urgent necessity is to make sure of our warning against prejudice. Strange to say the necessity of this warning may not be understood, and there are good reasons for expressing the fear. Prejudice against anything Spanish is part of the inheritance of English-speaking peoples. It is in their blood. Its sources are both political and religious. To remove them it is first necessary to uncover them. That may take a little time, but it will be time well spent for those who do really wish to get at the truth.

It is not difficult to find the reasons for our dislike of Mexico and Mexico's dislike for us. For the latter the story is spread over the record of our dealings with Mexican problems; for the former, it may be had by an honest confession of what is in the minds and hearts of the majority of English-speaking people. It will profit us to take a look at both.

Bruce, in his Romance of American Expansion,3 quotes from a letter of Thomas Jefferson, written from Paris, which gives us a lead in trying to learn what Mexico has against us. Speaking of the Spanish-American countries Jefferson wrote: "These countries cannot be in better hands. My fear is that they are too feeble to hold them till our population can be sufficiently advanced to gain it from them piece by piece." No statesman, and Jefferson was a statesman, ever wrote two more undiplomatic sentences. But they did represent, not only the ambition of Jefferson, but of the American statesmen of his day, and of many days and years to follow. They actually represented the ambitions of American statesmen well into our own day. One credit at least may be given to Woodrow Wilson's handling of Mexican troubles: he "sold" to the American people the conviction that they did not want Mexican territory or any other territory than that which they possessed. But the sale came too late to save us from well-grounded suspicion of our purposes in their regard, on the part of Mexicans.

Mexico to us would be no asset. It would tax our assimilative digestion into ulcers, as overeating taxes the stomachs of the strongest men, not because of the richness of the food but simply because there is too much of it. Absorption of Mexico would hurt our fruit-growing states, multiply our agricultural and labor problems, and end in movements for secession. Every advantage we could gain would be offset by greater disadvantages.

The Mexicans knew what our statesmen had in mind, for there were others besides Jefferson who let their pens and tongues betray them. Many in Mexico were not slow to take advantage and preach hatred of "The Colossus of the North," cleverly suggesting, usually for personal or political advantage, the thought that Mexico needed patriotic defenders against aggression by her neighbors, and that they could be trusted to be all of that. The United States was pictured, not only as the Colossus, but as an ugly one with an insatiable maw for territory. Religious fears likewise were played upon. That particular thought of fear especially was planted deep in the Mexican mind. It will take a stronger arm than was Wilson's to pull it out.

The revolutionary Mexican element, the self-styled liberals, saw a perfectly marvelous opportunity for themselves in all this. Within Mexico they could appeal for support to the popular fear of the Great Colossus. Outside Mexico, that is, in the United States, they could play their Gringo fish with the bait they knew would please his taste. Enemy within, friend without! That was the idea. And the American statesmen of the pre-Wilsonian age took the bait, "hook, line, and sinker." They initiated the only American policy toward Mexico that always has been consistently followed, viz., help revolution; what was in must be bad; put it out. Perhaps Polk and Buchanan, of all our Presidents, did actually distinguish themselves most in carrying out this policy. More than once Mexico came to the very brink of ruin because of it.

Now, if this policy of sympathizing and aiding every bad revolution in Mexico had been formulated officially, and handed down from administration to administration as a well-thought-out plan to achieve Jefferson's dream of Empire, it would deserve praise at least for the sagacity of it. No policy toward Mexico could be more certain to produce the result that Jefferson hoped for. From the revolt of Hidalgo in 1810 to the present time, revolutions have been sucking the very heart's blood out of the country. Once Mexico was ahead of us in practically all the things that mark an advancing civilization.4 We passed her while revolutions halted and then sent her into a decline that Díaz stayed temporarily. The steady deterioration of the nation is an undeniable fact. Many who live today have seen much of the decline pass before their very eyes. How long can Mexico stand blood-letting and destruction before she calls from the depth of her misery for the pity and guardianship of the much-hated Colossus? And what will the Colossus do with her when that time comes? Whatever he does, if he continues to be deaf, dumb, and blind to her best interests, will only make her fate worse and his with it. But the Great Colossus will not be Mexico's worst betrayer. He may be a Pilate, but he will not be a Judas. Mexico's Judases will be found in the long line of disturbers and thieves, who, for selfish ends, have made a mock of the power of the ballot while they appealed to the power of the sword. Two will stand conspicuous at the head of the line: Juárez and Calles.

Only a miracle of statesmanship, a miracle no student of her history may now dare hope for, can save Mexico from becoming a political and industrial slave of the Colossus. It is too much to hope that she will be made a partner. She may retain a semblance of freedom, but it will be a semblance only. Who is not sad to see a once promising nation perish at the hands of her own sons? Do not think, however, that we have statesmen so dishonestly astute as to make such a plan for taking Mexico with no loss of life and treasure to us but much to her. These statesmen of ours who followed the Fathers of the Republic, and especially those of the Polk and Buchanan type, never had it in them to do it.5 It was all an accident born of their prejudices and lamentable ignorance of the truth about Mexico and Mexicans. All this the intelligent and patriotic Mexicans know. Is it any wonder that they should dislike us? Had we done to Canada one tenth of what we have done to Mexico, her people would have for us a hatred undying.

There is, nevertheless, a word of excuse to be offered for what the rulers and the ruled of our country did to Mexico. We mentioned ignorance. Self-deception would have been a better name for it. In 1810, when Hidalgo raised the first standard of revolt in Mexico, we were at the very summit of our enthusiasm for the republican form of government and, therefore, in no condition of mind to understand the fact that what worked with us need not necessarily work with others. The great truth we forgot was that the application is not the principle, methods of enforcement not the law, a republic only one acceptable form of government. It works where it works. It is not adapted to all peoples. The great desideratum is good government in a form suited to the case. We are always making the mistake of taking the means for the end. We did it in dealing with Mexico. We do it every day in dealing with ourselves. Witness our mistakes about education, now becoming so plain and leading our youth into formerly unsuspected dangers. We so loved what we had, it was so good in our eyes, that we wanted Mexico and all the Americas to have it. There is our one excuse.

So much for the reason Mexico dislikes us. What about our half-dislike of Mexicans? It comes from two sources: racial tradition and religious prejudice. Take them in that order.

English-speaking peoples inherit a hatred for Spain which dates from the reign of Elizabeth of England. It was engendered by a compound of national rivalry and jealousy; by the marriage of Mary I to Philip II, and the attack of the Spanish Armada. When the ships of Philip broke up on the rocks of the British Islands, the reaction to deadly fear on the part of the English crown and people was a hatred strong enough to keep flowing with the blood in the veins of their descendants, disease enough to affect all who, through speaking, hearing, and writing in the English tongue, came into intimate association with them. No reader needs proof of that. If he is honest with himself he knows that he is himself the proof. The Mexican revolutionist too knew this. That was why he kept persistently crying to us that he was fighting the Spaniard, even long after the Spaniard had been crushed and expelled from the colony. The propagandists for Villa and Carranza used this prejudice constantly in dealing with American public opinion. Calles uses it today. The next revolution will use it, not to fight Spaniards but to fight Mexicans. Spain has no power in Mexico. Her civilization has all but passed. Spanish art in Mexico remains only in her monuments. The great Spanish cities that profoundly impressed the traveler from strange lands are no more. The University of Spanish foundation, equal to those of Europe, has all its glory in the past and little hope for its quick return in the future. In Mexico, Spain, except for her language, is a memory. Nevertheless those who have inherited the English hatred for Spain may still be influenced by the thought that she lives in the speech and writings of the educated, and in the values of her culture that still linger in the soul of the Mexican people.

Our success in building a nation, when compared to the failure that is present-day Mexico, is used to deepen our conviction that nothing good could ever have come out of Spain. We see only one side of the picture. Spain's success in Mexico and South America is one of the greatest wonders of history. It was not Spain but Mexico that failed. The Spaniard left a civilization. It is the Mexican who is destroying it.

Turn again to the record. The Visigoth invaders of Spain did not exterminate the Iberian and Celtic natives. They made a kingdom out of them. They mixed blood with them. They became Spaniards. That tradition of dealing with a conquered people they sent across the Atlantic with the Conquistadores. The Spanish did not do with the Indians as did the English colonists. They preserved them, educated them, and founded the prosperity of their colonies upon them. Cortés, cruel in war, changed, as soon as the City of Montezuma was taken, into a wise administrator protecting the new subjects of his King.6 There were abuses, but local and individual ones. Lummis says:7 "The legislation of Spain on behalf of the Indians everywhere was incomparably more extensive, more comprehensive, more systematic, and more humane than that of Great Britain, the Colonie...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- CONTENTS

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- PART ONE STUDY AND NARRATIVE

- PART TWO CHRONOLOGY, NOTES, AND DOCUMENTATION